The term ‘mechanical’ : Greenberg also uses the term ‘mechanical’ to describe a characteristic of kitsch and is also used in describing the processes of producing some Pop Art.

Thinking about Postmodernism in comparison with Modernism

Postmodernism is typically defined by an attitude of skepticism, irony or rejection towards ideologies and various tenets of universalism, which included objective notions of reason, human nature, social progress, among others. Moreover, this movement is associated with schools of thought such as deconstruction and poststructuralism.:

Tate says the following on their website

Postmodernism can be seen as a reaction against the ideas and values of modernism, as well as a description of the period that followed modernism’s dominance in cultural theory and practice in the early and middle decades of the twentieth century. The term is associated with scepticism, irony and philosophical critiques of the concepts of universal truths and objective reality. It has many faces in art:

- Anti-authoritarian by nature, postmodernism refused to recognise the authority of any single style or definition of what art should be.

- It collapsed the distinction between high culture and mass or popular culture, between art and everyday life. Because postmodernism broke the established rules about style, it introduced a new era of freedom and a sense that ‘anything goes’.

- Often funny, tongue-in-cheek or ludicrous; it can be confrontational and controversial, challenging the boundaries of taste;

- but most crucially, it reflects a self-awareness of style itself.

- Often mixing different artistic and popular styles and media,

- postmodernist art can also consciously and self-consciously borrow from or ironically comment on a range of styles from the past.

Avante Garde and Kitsch

Avant Garde as a linear notion of time –

- social commitment

- aesthetic achievement

Examples of kitsch may be particular to a time and place or they may be universally applicable: Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post magazine covers epitomize American World War II-era kitsch, whereas global kitsch resides in souvenir replicas of famous tourist landmarks the world over. Works of art that predate the introduction of the word into the vernacular are now deemed kitsch retrospectively: Pre-Raphaelite paintings and some Wagner compositions have been aligned with the theatrical emotionalism and affectation of kitsch. Indisputable examples of high art can be transformed into kitsch, prompting Matei Calinescu’s directive that, “determin[ing] whether an object is kitsch always involves considerations of purpose and context.” [4] Thus, Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street: A Rainy Day is not kitsch, but umbrellas sold at the Art Institute of Chicago decorated with the painting’s reproduction are definitive kitsch, as would be “a real Rembrandt hung in a millionaire’s home elevator,” according to Calinescu. (see Figure 2).

Kitsch tends to mimic the effects produced by real sensory experiences [compare simulation/simulacra , (2)], presenting highly charged imagery, language, or music that triggers an automatic, and therefore unreflective, emotional reaction. [5] Pictures of couples silhouetted against sunsets or songs with lavish, repeated crescendos elicit a conditioned response from a broad audience. Milan Kundera calls this key quality of kitsch the “second tear:” “Kitsch causes two tears to flow in quick succession. The first tear says: How nice to see the children running in the grass! The second tear says: How nice to be moved, together with all mankind, by children running in the grass! It is the second tear which makes kitsch kitsch.” [6] The appeal of kitsch resides in its formula, its familiarity, and its validation of shared sensibilities.

just as the baton of avant-garde art passed from Europe to the United States after World War II, so the most important critics were now American rather than European. No figure so dominated the art criticism scene at mid-century as Greenberg, who was the standard-bearer of formalism in the United States and who developed the most sophisticated rationalization of it since Roger Fry and Clive Bell.

Thierry de Duve: The Monochrome and the Blank Canvas

Non-art came into being inadvertently, in five successive stages and at the confluence of four factors. We will visit the five stages as we go along, each one made visible by a particular event.

The four factors are:

- (1) the existence of the Beaux-Arts system and the classification of the arts within it;

- (2) the “all or nothing” paradigm resulting from the binary character of the jury’s verdict at the Salon;

- (3) the convergence of aesthetic expectations in the notion of the tableau; and

- (4) the psychology of the jury.

When one institution collapses, another takes its place: History, like nature, abhors a vacuum. The new institution, in which we still live and which I call Art-in-General, has negativity branded on its birth certificate—negativity resting on betrayal and fueled by denial. I doubt it’s the kind of dialectically positive negativity Buchloh has in mind when he argues that artistic production should be judged “by its dialetical capacities of critical negativity and utopian anticipation”—but who knows? Ask the messenger, read the message, there is still more to it.

Coming to grips with art which I do not particularly appreciate and or pretend to understand as art, due to lack of “seeing it”, battling to grasping it /understand it/comprehend it/ contextualise it, going behind the face value of the work.

I looked at the work of Robert Ryman, an American abstract artist:

It’s not a blank canvas,’ protested Robert Ryman, the American abstract artist, standing before one of his canvases – as flawlessly smooth and white as the Tate Gallery wall behind it. ‘It’s got a lot in it,’ he added. ‘This has to do with the light. It looks very different in different light.’

Ryman had flown into London from New York last week for a retrospective exhibition of some 75 works. Opening at the Tate tomorrow, and organised in association with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the show will pay homage to one of the leading figures in American abstract art – an artist who is said to have bridged the gap between Minimalism and Abstract Expressionism through his primarily ‘white paintings’.

For Nicholas Serota, director of the Tate Gallery, Ryman is ‘one of the most important abstract painters of his generation. By limiting himself to an area of the palette, as it were, but working on all kinds of materials and surfaces, he has stretched the boundaries of painting. In particular, he has drawn attention to the importance of light in painting.’

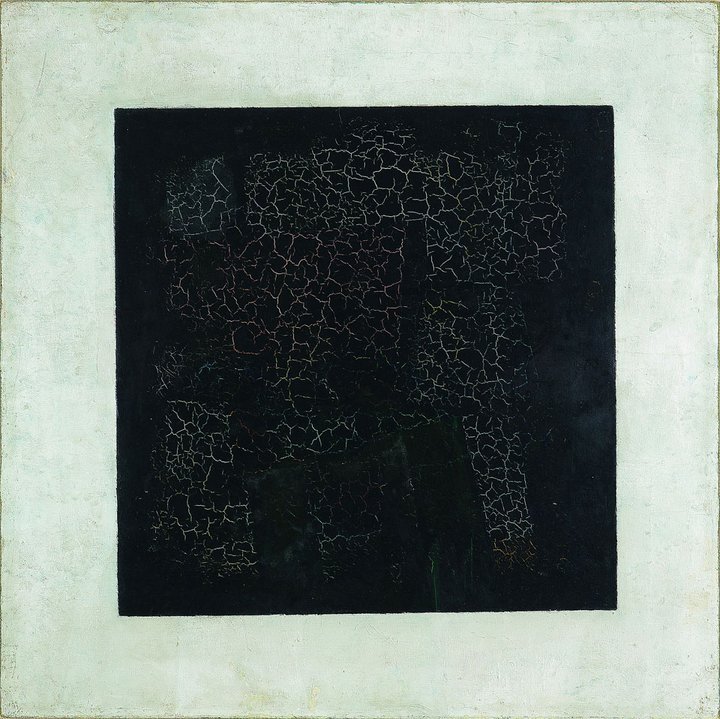

An interesting reading on the Russian artist, Malevich ( 1878 -1935) and suprematism and teachings in the post Revolutionary art schills, where academic training was replaced by an innovative multidisciplinary approach , very much in common with the Bauhaus. In the 1910s, Malevich adopted Cubo-Futurism, a Russian avant-garde style that combined Cubism and Futurism. He then developed what he called Suprematism and started painting geometric shapes instead of figurative subjects. Black Square was the culmination of this concept.

His Black Quadrilateral, c 1913 – 1915 was revolutionary as it hung in a gallery on the traditional place where Icons hung previously. The inspiration for the work came in 1913 while Malevich was working ons designs for the opera, “Victory over the Sun” – this represents the eclipse of the sun, and to be seen as a symbol of the dawning of a new era. On the Tate website I found this: “Malevich promoted it as a sign of a new era of art and he saw it as beginning at zero. That’s why he added ‘0.10’ to the exhibition title of his 1915 exhibition. (However, although he declared the Black Square as the first suprematist painting, x-rays show a multi-coloured suprematist composition underneath).”

So much more is seen in this painting – a triumph of the new order over the old, of the East over the West, man over nature, idea over matter. The geometry is an independent abstraction in itself – superseding the Christian trinity and symbolizing a ‘supreme” reality. The flat planes replaces volume, depth and perspective as a means of defining space, each side represents one of the 3 dimensions, the fourth side standing for the fourth dimension, time! The black surface would be the infinite, were it not delimited by an outer boundary which is the white border and shape of the canvas – like the universe itself.

According to Tate, this was the first time someone painted something that was not ‘of something’. “Painting was the aesthetic side of a thing, but never was original and an end in itself.” the Tate comment.

On Black painting – more on Tate website – When Black Square was first exhibited people found it a strange thing and people still find it a strange object today. There’s no wrong or right way to look at it. It could be a window into the night, or you could see it as just a black shape on a white canvas, (which is more of what Malevich was intending). Malevich set out to change forever the idea that painting has to represent reality. It’s intriguing to think how doing something simple or even seemingly dull, can sometimes be revolutionary. That’s what makes the Black Square a radical thing, however you look at it”

Interesting recent research revealed through X ray – is that there is a previous painting underneath the Black Square of Malevich. The x-ray analysis also uncovered a handwritten note by the artist on the painting’s white border which is still being deciphered. However, according to AFP, preliminary investigations have revealed that the text says “Negroes battling in a cave.” The note may be a reference to an 1897 black square painting by the French writer Alphonse Allais titled Combat des Negres dans une cave, pendant la nuit (“Negroes Fighting in a Cellar at Night.”) If the preliminary interpretation holds up, it could support a connection to the earlier French painting, demonstrating that one of Malevich’s most famous works was in fact an art historical response or an interpretation of Allais’s piece, showing that the Russian artist’s pool of influences had been much broader than previously thought.

Can I thus come to the understanding that:

- painting/art can be pure fact

- it is absolute – art that is not representational, does not have to represent anything

- simplistic elements make a picture

- visual components is abstract components

- away from the abstract ideal – more truthful, as the lines are wonky

- see the originality of being hand made

- Everything one sees is part of the visual field, as such it has pictorial value, it’s capacity to be seen other than what it is, the black square as showing geometric perfection or absolute flatness too idealistic,

- In order to call a picture art, you need to ‘see’ it as art – knowledge about art is exclusive, what about own likes in terms of aesthetic and visual interest and connection.

- art criticism is a subjective field and even if there is a universal theory on quality, it often fails when applied to the particular work of art.

- Museums and their role in art history and art ‘promotion’.

- Influence of sophistication, theorizing, institutionalisation of art.

- Did art always have this play between beauty of creating and the sake of sophistication/pretense

“In fact, this worshipping at the altar of abstraction is deeply questionable. The contentedness of abstraction can be as limiting and as dull as any attempt to paint the world. What is more, the human mind is always so curiously undependable, that even the starkest purist cannot stop himself looking for signs of the world in the most abstract of works. Otherwise, what exactly is it that we are supposed to be looking at, and can this ever-elusive something really hope to sustain us to the depths of our emotional natures?In short, why, Mr Malevich, did you go back to painting people in the end?”

Above is taken from an article in the Independent by Michael Glover dated 16 July 2014: Kasimir Malevich’s ‘Black Square’: what does it say to you?

Allan McCollum : Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates

Allan McCollum, a self-educated artist who was questioning the uniqueness ascribed to artworks, created 40 Plaster Surrogates (1984), a huge series of objects that appear like paintings but which are actually blank, theatrical stand-ins for such, and point to the era’s irony and humor as dominating artistic devices.

The Surrogates aren’t pictures of anything; and one looks no better than another. I’m trying to provoke a slightly schizoid feeling of “walking through” a situation, of performing activities without the kinds of excuses one generally uses to do so, not because I think people should behave this way all the time — and I certainly don’t think everybody should be making pictures like mine — but because if one experiences one’s activity with some of the standard mystifications removed, one learns certain things about oneself that one doesn’t learn when one is engaged in a more direct way. I’m trying to orchestrate a sort of charade–like a ritual re-enactment, or a child’s game — which includes not only the art gallery, but the social behaviour which inspires — and is inspired by — the art gallery. I think that an analysis should always begin with pinning down one’s own position, and it is my position in the world as an artist which I aim to characterize in this project, to even mock myself, perhaps, and to try to tip the seriousness of my critique slightly over into the realm of play.”

If modernism insists that the artist “make it new,” creating an object that is forever fresh and self-renewing, the dinosaur is unimaginably old, a symbol of failure, obsolescence, and petrified stasis. If modernism demands the original, unique, authentic object created by the artistic imagination, the dinosaur is a mere copy of a fragment of a corpse or skeleton, a fossil imprint produced by natural accident, not by human artifice. If modernism demands the elite, refined, purified objet d’art, the dinosaur is contaminated by its status as a commercial attraction, its function as a mass cultural icon and an object of childish fascination.

A rather different variation on the postmodern strategy of “paleoart” is offered by Allan McCollum, an artist who is perhaps best known for his Surrogate Paintings and Plaster Surrogates, cast objects that look like blank pictures in sleek modern frames, hung in clusters like an array of paintings in a Victorian study gallery. Like Dion, Every picture is unique—or at least the frame is—but at the same time they are all exactly the same, epitomizing the kind of serial repetition that is characteristic of images as species or genera of artifacts. You’ve seen one McCollum surrogate and you’ve seen them all, yet none is exactly like any other. It is as if McCollum were imagining a future world in which all the pictures had gone blank, could no longer be seen or deciphered, but all remained in their positions on the walls. They hint at a world in which pictures would be fossils, traces of vanished, obsolete species. Perhaps this would be a world of the blind, in which pictures would function as sculptural pieces, and we would grope along the walls to be reassured by touch that they were still in their places. Or perhaps it would be a world in which people were so imaginative that they could treat any blank space as a projection screen to recall any memory or fantasy they desired. We might even see here a premonition of the virtual galleries Bill Gates is installing in his electronic Xanadu in Seattle, galleries in which images from a global data base can be retrieved with the click of a remote control. In any event, McCollum’s surrogates invite us to reframe the entire convention of pictorial display, to see a gallery the way an archaeologist might see an excavated treasure room, as a strange space filled with shapes and signs that may have lost their meaning, or may never have had any meaning in the first place. The effect is a curious combination of irony and melancholy, what Fredric Jameson has aptly termed “nostalgia for the present” endemic to postmodernism.

Other artists

Eva Hesse – whom also focussed on the process of art through her career. Below is her polyester resin sculpture, Expanded Expansion. The following materials form the art work: fiberglass, polyester resin, latex, and cheesecloth, the work was done in 1969. While its height is determined by the poles, the width of the piece varies with each installation; like an accordion or curtain, it can be compressed or extended.

Have Modernism moved past Post Modernism?

In a thesis of an M Art student the following is said:

However, there are six major distinctions that set this new, dynamic art movement

apart from Postmodernism:

- the rise of art as commodity and artist stars,

- a focus on galleries,

- globalization and

- an increased dissemination of information,

- a focus on intermedial artistic practices, the overwhelming meta-mentality of artists,

- a re emergence of traditional painting and photography.

Further reading I would like to continue

Hockney has written a book in which he also theorized that Rembrandt and other great masters of the Renaissance, and after, used optical aids such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and mirrors, to achieve photorealism in their paintings. His theory and book created much controversy within the art establishment, but he published a new and expanded version in 2006, Secret Knowledge: Rediscovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters (Buy from Amazon), and his theory and Jenison’s are finding more and more believers as their work becomes known and as more examples are analyzed. The documentary, Tim’s Vermeer, released in 2013, explores the concept of Vermeer’s use of a camera obscura. Tim Jenison is an inventor from Texas who marveled at the exquisitely detailed paintings of the Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675). Jenison theorized that Vermeer used optical devices such as a camera obscura to help him paint such photorealistic paintings and set out to prove that by using a camera obscura, Jenison, himself, could paint an exact replica of a Vermeer painting, even though he was not a painter and had never attempted painting.

Museum visits during November 2018

Visit to Barcelona’s Museu D’art Contemporani de Barcelona

The museum ran a chronological display in rooms on the last nine decades, with emblematic moments. The exhibition is called: A Short Century and on the front page of the brochure there is a picture of the Guerrilla Girls, Do Women Have to Be Naked to Get in the Met Museum? Interesting is how the art of Barcelona and Spain is linked into the theme – such as the Spanish Civil War ( 1936 – 39) , Franco dictatorship, Civil Rights, Radical Feminism and Feminist activism, Gender stereotyping, anti-racism, gay rights and identity politics, Pop culture, installation art, geo- politics and critique of economic relations governed by neoliberalism, globalisation and unequal distributions of power.

Here is a work by Basquiat – self-portrait, revealing his awareness of the currency of his own image as an artist and as a black male body.

Visit to Museo Picasso de Barcelona, November 2018

This opportunity was great in many ways – I loved the drawings of figures in his early life and the big area given to the works done on the Las Meninas. From his first trip to Madrid and visit to the Prado in 1895, Picasso had the chance of direct contact with Velázquez’s work. During his 1897-1898 stay, he preferred to be a copyist at the Prado rather than take classes at the San Fernando Academy of Fine Art. Here he was able to study Las Meninas in depth. A copy Picasso made of Velázquez’s portrait of Philip IV also dates to this time could seen at the Museu Picasso.