CONSIDERING COLLABORATION, NEW MATERIALISM and DEVELOPING the BODY of WORK

It became important to consider mushrooms and lichen as a subject matter, and look at their potential as a medium. From Tsing, I learned that collaboration could be ‘multi-sited‘. Opportunities to forage opened up in the winter of 2022. I saw the potential for involved processes of making and learning. I would like to consider the artist as not necessarily the primary ‘active’ maker/agent, and see my own work or making as working and thinking with or through material; a form of ongoing collaboration.

Having now also read Petra Lange-Berndt’s essay, How to be complicit with materials,(Materiality Documents of Contemporary Art: 12-20) for a reflective exercise in Part Four of the Study Material; I found a few questions resonating with me in terms of making work and thinking about materiality as a topic for my Critical Review. Lange-Berndt discusses it as an anthology which focuses on the “moments when materials become willful actors and agents within artistic processes, entangling their audience in a web of connections.” By doing this, material investigates the role of materiality in the art that attempts to expand notions of time, space, process, or participation. (2015:18-20)

- I do like the idea that materials are complicit when we as humans make and attempt to communicate something with meaning in our artwork.

- Words or ideas when one follows material she mentioned, resonated with how I look at fungi and lichen as material: “….means to enter a true maze of meanings, where on encounters terms such as matter, material, materiality, Stoff, substance or medium.” (Lange Brandt 2015:14)

- I related to these ideas better when I later started working with real foraged mushrooms outside in their natural environment.

- In the part where Lange writes about “Experiment with Unknown Possibilities” (2015:16-18) she considers ‘following’ the material and looking at the contemporary discourse of Jane Bennett who writes as ‘vibrant matter’ or ‘agential’ realism.

I want to share the work of a fellow student of the OCA whose work I find inspiring. I have been following Inger Weidema on IG for the last year or so after I met her online in the OCA EU group. I enjoy the living subject as the art in the work below (Fig. 1) and felt that she brings a form of minimalistic collaboration into play. I remember one of her IG posts, where she wrote about the work below, describing it as minimal intervention.

In our WanderWide Web group (online exhibition) Inger a student on the Textile course shared work I wanted to place on the OCA EU group IG account, in the build-up for our online exhibition. The thoughts she shared captured my ideas about fungi and collaboration with the non-living. She titled the work above, Conspiring with plants (Fig. 1), and wrote the following:

“This piece is inspired by the radical truth that we live in a green cosmos on a blue planet because of plants. The unmoving plants enable our worlding – they are the true first movers – world makers. We depend on plants for matter and oxygen production. We, the rootless, need to do life otherwise, to conspire with plants (to freely quote Natasha Myers). A first step is to try to alleviate our plant blindness and learn from plants.” (quote was written by Inger Weidema and shared on our group G drive as a folder I could use for IG. The work is suspended to hang in the exhibition)

Material exploration of mushrooms and conceptualization of ideas

I look at nature as a concept being shaped over millennia, and as such, it is (has been) defined by our histories, cultures, desires, spirituality, pasts, cross-breeding, grafting and even futures. It seems one has to consider within this ( a type of trace/graft) that there will always be a process of negotiation between one’s own cultural background, race, gender, beliefs, and values. Our coming to terms with the vegetal world is always inescapably mediated by contexts, even when we try to claim to be objective. I am more focussed on developing my practice around nature and feel sensitised to questions like:

How is it possible for us to encounter plants?

How does the world appear to plants?

I had a few discussions with fellow students/artists around this and am more convinced that non-Western and Feminist philosophies will be the place to research for this answer, as I am convinced that current capitalist ideas are that the environment is seen as ‘another thing‘ to be manipulated for our own purposes. Through these questions, I have started reading a new book by Michael Marder, Plant Thinking (pdf downloaded from Columbia University Press). I like the idea of plants (and mushrooms) as beings that have roots – their rootedness to the soil. Other words that come to mind are that they grow, they vegetate, they animate, they are alive.

I wanted to react to the idea of using ‘radical’ in writing, a word I encounter regularly in my current reading. My thoughts are based on how we need to (re)consider our practices in our relationship with nature. I wonder about showing the hidden or working with the unknown (and self-consciousness).

I learned from anthropologist Tim Ingold that ‘umwelt’ is not a fixed sensorial idea or tangible category, but it is an active process of making by different species. To me, it is about sensing (becoming aware of) this engagement – a continual process of forming relationships. I am reminded of something I read at the beginning of this course as part of a reading group and reflected on in Part One when an exercise asked me to use a map/diagram to reflect on the making processes. Ingold (2007:84) views maps drawn by humans as a gestural -re-enactment through lines of movement of journeys actually made. I am thinking in terms of walking in nature and collecting or looking at fungi, and ask myself if that can be seen as an embodied performance. Am I ‘reading’ something about nature when I interact with mushrooms?

I have now learned that our human bodies are hosts to hundreds of different fungi, which is again an important part of our microbiome, and in this case, our body becomes the habitat for this community of microorganisms. These fungi live all over our bodies. Sheldrake writes so eloquently, (p211): “For as long as fungi have existed, they have been bringing about a ‘change from the roots.’ For Sheldrake, us humans are the latecomers to this story. Marder refers to traces of each other, plant and human that both of us carry. (p30)

In her book, Ancient Plants, Stopes noted: “[S]o quietly and so slowly do [plants] live and move that we in our hasty motion often forget that they equally with ourselves belong to the living and evolving organisms” (174). (Stopes, Marie Ancient Plants: Being a Simple Account of the Past Vegetation of the Earth and of the Recent Important Discoveries Made in This Realm of Nature Study, London: Blackie & Son Limited, 1910)

Considering anthropomorphism and the agency of nonhumans

Whilst reading The Hidden Life of Trees, I wondered if the writer has not come to a point where he confuses science and his own ideas and imagination. I considered anthropomorphism or even ‘fetish’ and interesting to find in my research, that Charles Darwin, after writing about the Earth Worms was also ‘accused’ or ‘inveterate anthropomorphism. Jane Bennet wrote about Anthropomorphism and I felt I need to revisit these ideas. I quote the below passages from the book, Vibrant Matter (99)

“In a vital materialism, an anthropomorphic element in perception can uncover a whole world of resonances and resemblances—sounds and sights that echo and bounce far more than would be possible were the universe to have a hierarchical structure. We at first may see only a world in our own image, but what appears next is a swarm of “talented” and vibrant materialities (including the seeing self).”

“A touch of anthropomorphism, then, can catalyze a sensibility that finds a world filled not with ontologically distinct categories of beings (subjects and objects) but with variously composed materialities that form confederations. In revealing similarities across categorical divides and lighting up structural parallels between material forms in “nature” and those in “culture,” anthropomorphism can reveal isomorphism. “

When I started this exploration I became aware of how I, as a layperson, should look to information shared in books and articles if find online. I should be aware of how authors can use speculation and imagination in this mix. Trying to understand anthropomorphism is that what stood out for me is that by recognizing similarities between me (human) and the other (plant, animal, living organism, etc) I focus more on the recognition of similarities and this draws my attention away from my own ‘human concerns. Being a child of Africa and having quite a good knowledge about our bush, trees, plants, birds, and animals, it is sometimes difficult to place me in a European forest. My knowledge and experience are of a much different environment – as well as the effects of man versus the wild in the way we developed and live. South Africa is a very diverse country when it comes to nature and we have many biodiversity ‘hotspots’, which makes protection a serious concern.

Making a list of concerns:

- Land and soil degradation

- Climate change – getting warmer and less annual rainfall

- Human-induced pressure on ecosystems

- Hierarchies of race, class, gender

- Food security

- Water security

- Conservation

Where I live not many indigenous trees occur and I am very aware of the threat of the alien species, mostly growing on farms in this area, to our natural water supply and flora, where invasive plants are becoming a bigger problem to control. I have learned that Blue Gums (image below) use allelopathy: By releasing chemicals that other plant species don’t like, they displace native species, improving conditions for themselves – in this way eliminating competitors. (https://blog.invasive-species.org/2020/01/21/eucalyptus-the-thirsty-trees-threatening-to-drink-south-africa-dry/). In the area where I live, the biome is seen as one of the most diverse in the world, and called the Cape Floristic Region, with more than 9300 described plant species, of which 67% are endemic to the region. The natural vegetation in my area, called “Renosterbos “, (Rhinoceros bush if directly translated from the Afrikaans language) is also disturbed due to the lands being planted with wheat and used as graze for sheep, and not much natural vegetation is found on our farm. This natural vegetation is mostly grass, bulbs, and shrubs,(many are herbaceous species). We do not have a variety of trees/forests in my area and unfortunately, the invader trees, such as the Eucalyptus from Australia are most prominent on the landscape. I am however interested in the termite hills we find close to indigenous trees, such as the Wild Olive species – I do know that the ants live underground, and need nutrient-rich soils. In these natural areas, I often see foxes, porcupines, shrub hares, small antelope, and obviously more diverse birds. I do wonder about life underground. I walk in natural areas with a group at least 2-3 times a week and have the opportunity to learn to get closer to nature in these areas, which are mostly around our local mountain or on farms.

The Anthropocene and how I view the place I live in

I recently listened to a Youtube video, called Creative Practice and the Anthropocene, and made me consider again my thinking of the environment as an artist and maker.

Here on a wheat and sheep farm, I am aware that due to the agricultural practices over many years, the land is disturbed and the soil might not have many natural multispecies living there. It is also known that fungi live in the roots of wheat plants, but fertilizers and spraying of fungal killers have interfered here. I do like to think that the use of legume rotations (we have medics, a family of the clover) and reduced tillage do play a role in the health of the soil. I have learned that Legumes have a symbiotic relationship with bacteria called rhizobia, which create ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen and help the plant. As my reading and research developed I discovered the work of artist Daro Montag. In a way, this artist strengthened my ideas about collaboration with living matter, in my case, The Fungal Kingdom. (see blog post on Artists I researched). I agree with this artist’s view that we are the soil that has learnt to talk and reflect on our place within the cosmos.

I became more aware of the vitality of soil and how fungi with mycelium became my way of reconnecting with the earth and becoming concerned with our dependence on healthy soil. Anna Tsing refers to damaged landscapes and environmental disturbance when she writes about the matsutake mushrooms which I believe is also a lesson in collaborative survival and recognition of relationships with other species to the benefit of all life forms. Tsing is an ethnographer and awakened me to attend to the ‘arts of noticing’ and become ‘respons- able ‘to see things as interactive and collaborative when I look to the non-human. I read that scientific studies confirm that mushrooms, for example, Agaricus bisporus, Pleurotus ostreatus (oyster mushrooms), Coprinus Comatys,(inky caps) and others could be used as a bioindicator of pollution of soil Toxic metals can be absorbed. (García‐Delgado, Alonso‐Izquierdo, González‐Izquierdo, Yunta, & Eymar, 2017). I understand that when we choose to consider place, plants become a great indicator of it – they are fixed in that environment and we enter it from the outside. Natasha Myers calls for different conceptual formations – to centre people and plants simultaneously, a type of ‘inter-being’, which she calls the Planthroposcene. It is a way how we could conspire with the plants – collecting up, to breathe together is the word she used in the podcast I listened to. (For the Wild Podcast on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JsvzerDapqA) It mainly calls for responsibilities and ceding control we assume over plants.

As a keen gardener, I have always made my own compost and see this humus as life-giving in my garden. Later when I started making spore prints with mushrooms I foraged around our house, I placed them in my vegetable patch after I had used or looked at them, hoping to spread spores and create mycelium networks and also to see this as my way to imagine a way to collaborating with the Fungal Kingdom as a new way of survival in our damaged environment.

Considering using field notes:

I plan to use my phone camera to take pictures if and when I find mushrooms/fungi/lichens around me.

It is summer now, but since we had good rains from late November into December, I have been finding mushrooms around our garden. I have no knowledge of the genus but can use my images to search this. I am intrigued by how a mushroom seemingly just pops up at a given moment, and if you are lucky, you witness this living thing. My husband has fond memories as a child foraging mushrooms with his mom. This took me to mushrooms that have intrigued me for a long time, namely a mushroom that lives in the desert here in Southern Africa – we know it by the name Kalahari truffle. I made contact with a supplier/forager, but according to him, these truffles will only be available during March/April 2022. It is also linked to the rainy season.

Example of field notes: Sightings listed during Summer

- 29 November 2021 small ones in upcycled wine barrel planter, among the Hydrangeas

- 3 December 2021 white ones on the grass patch in the front garden

- 7 December 2021 I found small ones in the veggie garden, see the images below

- 22 December 2021 rocks around Yzerfontein, mostly yellow and orange lichen found

- 30 December 2021 lichens in the stonewall outside our farmhouse, Riebeeck West

- 7 January 2022, lichens on the rocks at Jacobsbay walk along the beach

- 9 January 2022, lichens on decaying fynbos plants on the beach walk in Jacobsbay (could be Xanthoria parientina)

- 19 January 2022, mushrooms in the veggie patch inside the upcycled wine barrel, among the Hydrangeas.

Wild foraging and collecting of mushrooms

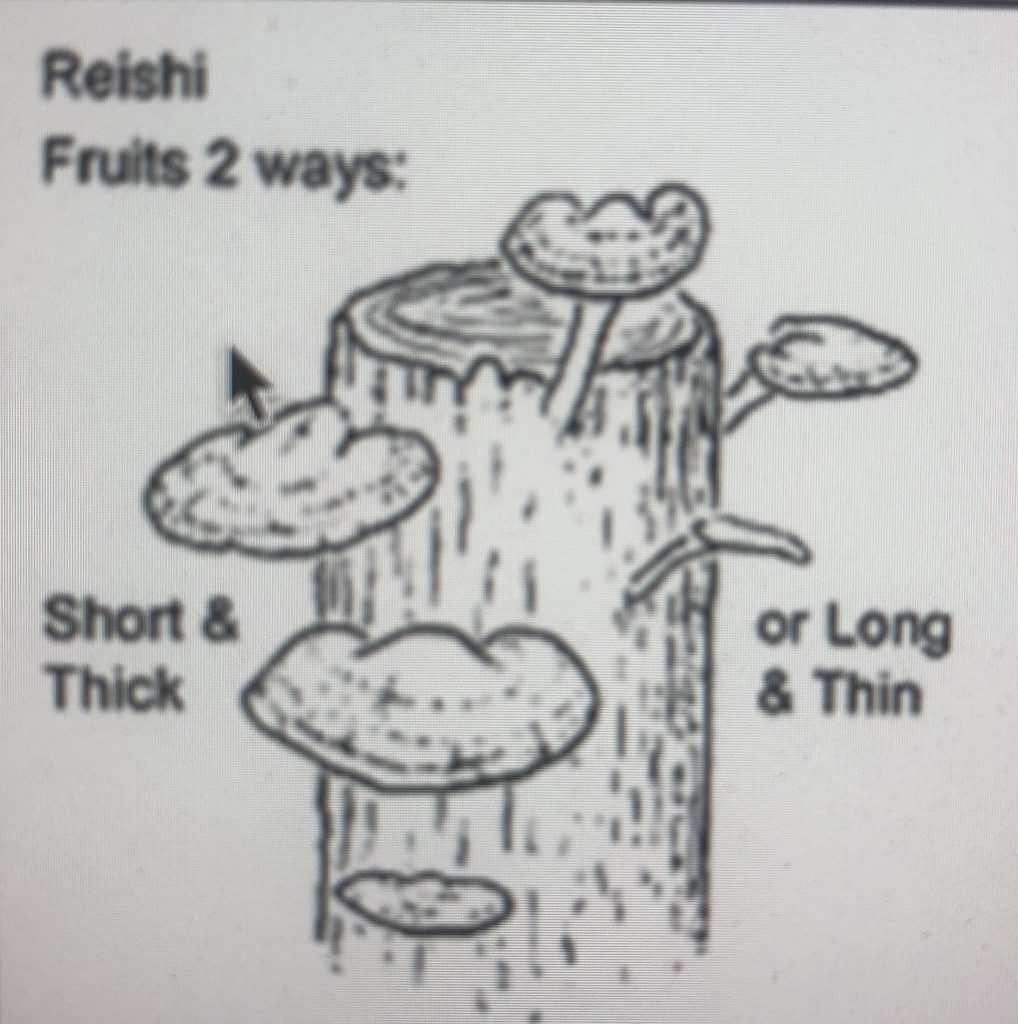

I hope that this can start by April 2022. I enjoy walking and have always seen this as part of my practice. I consider how the Fungal Kingdom would be seen as a subject within this walking and connecting with nature. Looking at how I can interact with Fungi, I contacted a local supplier (online) for mushroom cultivation and ordered (250) wooden dowels that carry the fungus for Reishi mushrooms. With this method I will be using a log from a local Karee tree, inserting the dowels into the log, placing it outside and leaving the fungus to colonize. I found a log from a local tree feller whom I searched on social media and was so happy to find lichen growing on it. I am supposed to wet the log at least once a week and the growth can be expected roughly within a year when mushrooms should grow from the surface of the log.

While the Boletus genus of mushrooms is the best to find in our area, others in the same broader family are the Bay bolete (Imleria badia), a symbiont of pine (Pinus) and similar in flavour to Boletus edulis. These mushrooms all form associations with a coniferous tree, (Pinus radiate) here in South Africa, and in the Western Cape, which is a winter rainfall area it fruits from mid-autumn until mid-winter. An interesting fact I learned about this fungus is that it doesn’t always grow mycorrhizae with trees and can switch to saprobic tendencies, meaning they feed on decaying matter, like leaves. Amazing abilities to adapt! This reminds me of Sheldrake’s writing about how fungi adapt to changing environments, a lesson we as humans need to learn. Does it talk to me about an agency to arrange and re-arrange? Interesting is that my friends with whom I forage have been going to the same spot for a few years, in order to find these ones in the image below.

In terms of my own local landscape, I learned that we have at least 94 edible species in South Africa which start to appear in late Summer, in the summer rainfall areas. In a book on local foraging, I found valuable information on what is locally called ‘veldkos’ and which forms part of an interesting cultural history of the indigenous black tribes in Southern Africa. This interesting history refers to the oldest tribe, the San people as hunter-food gatherers, who lived in Southern Africa as the principal inhabitants for at least 11 000 years. Fox & Young (1982:232-235) write about the different Fungi found to be part of the diet of many of the tribes. Here in the Western Cape Province where I live, the Boletus edulis is found and can weigh up to 2.5kg and measure up to 30cm in diameter. I am now more aware of my own engagement with the landscape – I walk regularly and started to forage mushrooms as well. I ask questions about indigenous and endemic – where do particular fungi originate from, I become aware that as trees were brought into our country during colonial times and are still ongoing, this changes the landscape of not only the natural environment but that of fungi to be found. Fungi form relationships with particular trees and as Tsing writes, we do disturb these landscapes. Our holiday at the seaside brought me into contact with lichens. I took many photos and brought some samples of fallen branches with lichen home to draw and study.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1 Weidema, Inger I. (2022) Conspiring with plants. [Photograph] At: https://www.spaces.oca.ac.uk/wanderwideweb/ (Accessed 08/08/2022).

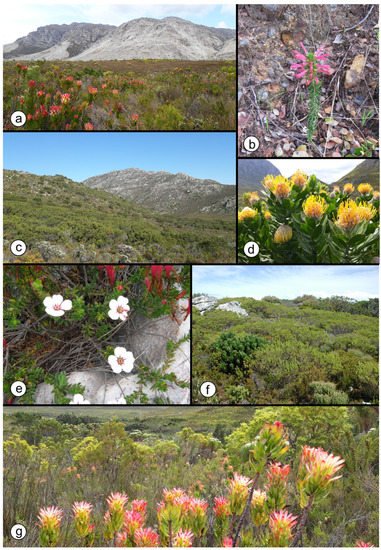

Fig. 2 Diversity, Volume 12, Issue 6. (June 2020) [Photograph series ] At: https://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/12/6 (Accessed 14/03/2022).

Fig. 3 Invasive Species Blog (2020) [Photograph of eucalyptus trees] At: https://blog.invasive-species.org › tag › eucalyptus-trees (Accessed on 14/03/2022).

Fig. 4 Mushroom Guru: illustration of Reichi growing [screengrab] At: https://www.mushroomguru.co.za (Accessed online on 17/01/2022).

Fig. 5 Stander, Karen (2022) Foraged Bolete mushrooms [Photograph] In possession of: the author: Langvlei Farm, Riebeeck West, South Africa.

Bibliography

Barad, K. 1989. Meeting the Universe Halfway Durham: Duke University Press, 2007.

Bennet, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: a political ecology of things [PDF] At: OCA library (Accessed 2/11/2021).

Lange-Berndt, Petra. 2015. Introduction, How to be complicit with materials from ed. Lange-Berndt, Petra Materiality Documents of Contemporary Art, London: Whitechapel Gallery and the MIT Press. (p12- 20).