Thoughts on life studies as a common subject throughout art.

Looking at human bodies in art is also a way of looking at ourselves. I interpret the part in the study material (p 86) referring to art history and long traditions of depicting or representing the human head and form, as a challenge to draw what I see, focus on my own perceptual skills and challenge my own ideas. I think about Picasso’s working premise that a portrait is a subjective document: a viewer recognises the artist first, the sitter second (if at all). I am also confronted with drawing the figure – the act of using lines to represent a human figure – how has this been developed since the first cave drawing was made?

My thought process is a moving figure, a living figure being in a space at a moment and documenting the figure at that moment. ( Klee saw the world as an active site for drawing. In many ways I see figurative painting, drawing, sculpting as a way to touch on the essence of human life. Then I do like the work of Daniel Maidman – who talks about ‘wu’ – an intense “itselfness” of an object that has to be in a work. He says the following in his blog, I have been following: “I believe the crudity of depiction is deeply linked to wu. There is a way that fine depiction distracts the mind from the essence of the thing. Too much naturalistic verisimilitude cheapens the experience of the thing; it clutters up the perception with virtuosity, and seeming-ness. To reach wu, one must strip away the properties of seeming and seek the properties of is-ness.”

It seems this art from was established by the Greeks in the fifth century B.C.E. ( Classical Antiquity) and later during the Renaissance, revitalised. Ancient Greeks used the nude figure to represent man in his purest from.

Above naturalistic sculpture shows a man standing in a relaxing pose – contra-posto. The body is represented as one would imagine the artist saw it – it reflects and understanding of a body in movement, how its weight shifts in movement, proportion, the muscles under the skin, contours of the body, and the bones under the flesh. During my research I read on the Khan Academy website the following on Representational Art: “The oldest of these is a 2.4-inch tall female figure carved out of mammoth ivory that was found in six fragments in the Hohle Fels cave near Schelklingen in southern Germany. It dates to 35,000 B.C.E.” I also came upon the Lion Man figure made of mammoth ivory and is a combination of a fierce cave lion and the human. It is said to be 40 000 years old.

I found an image carved in limestone, called Venus of Willendorf c.25000 – 30000 BC. This most famous early image of a woman was found in 1908 by the archaeologist Josef Szombathy in an Aurignacian loess deposit near the town of Willendorf in Austria and now in the Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna. It is miniature in size – 11.1 cm long

Little emphasis is placed on musculature or anatomical accuracy. We may infer from the small size of her feet that she was not meant to be free standing, and was either meant to be carried or placed lying down. The artist carved the figure’s upper arms along her upper torso, and her lower arms are only barely visible resting upon the top of her breasts. As enigmatic as the lack of attention to her limbs is, the absence of attention to the face is even more striking. No eyes, nose, ears, or mouth remain visible. Instead, our attention is drawn to seven horizontal bands that wrap in concentric circles from the crown of her head.

Little emphasis is placed on musculature or anatomical accuracy. We may infer from the small size of her feet that she was not meant to be free standing, and was either meant to be carried or placed lying down. The artist carved the figure’s upper arms along her upper torso, and her lower arms are only barely visible resting upon the top of her breasts. As enigmatic as the lack of attention to her limbs is, the absence of attention to the face is even more striking. No eyes, nose, ears, or mouth remain visible. Instead, our attention is drawn to seven horizontal bands that wrap in concentric circles from the crown of her head.

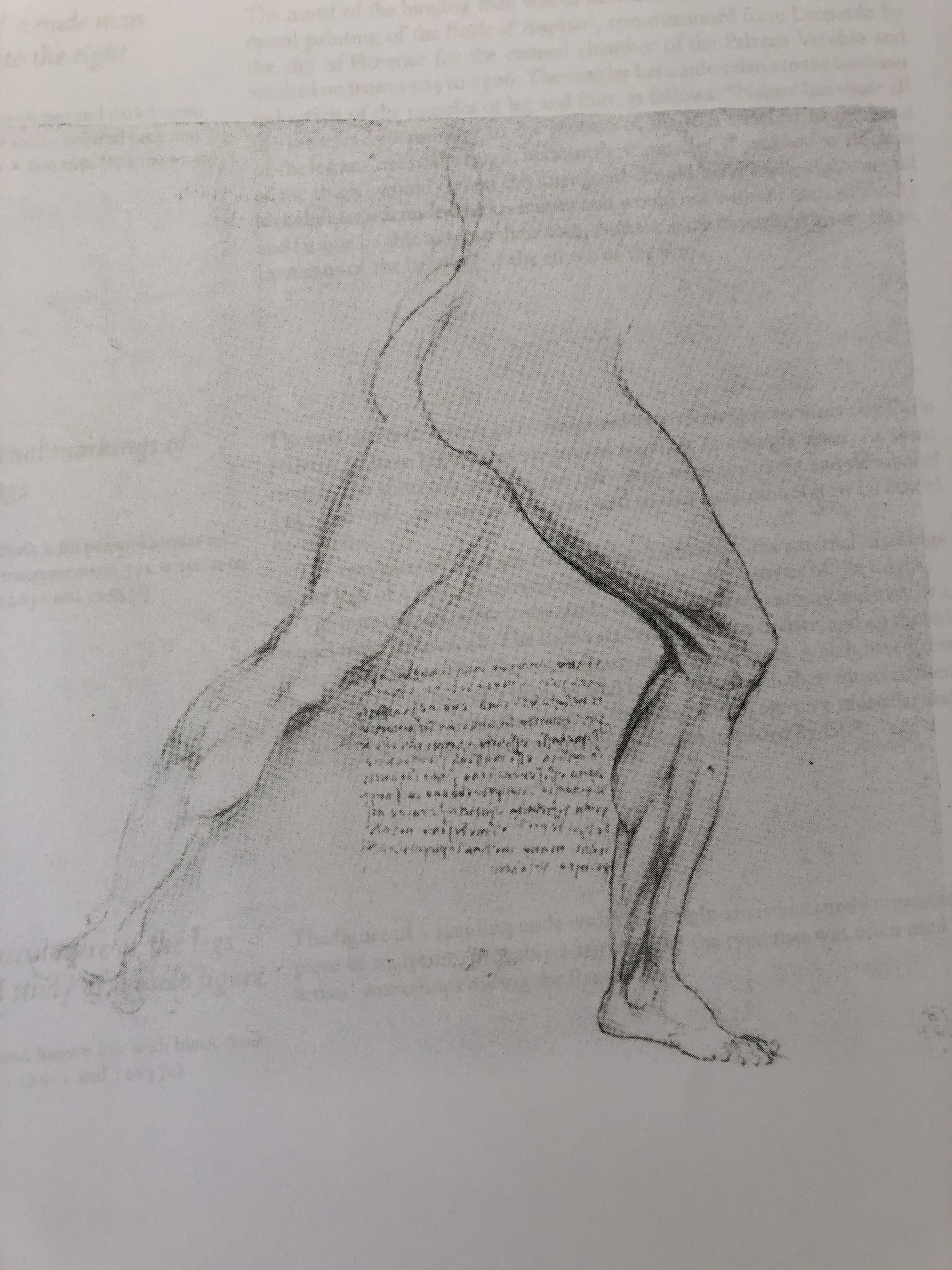

Figurative drawing in the Western Culture continued to be in the academic curriculum in the nineteenth century. The Greeks put great emphasis on physical beauty and ancient Greece sculptures of people show naturalistic free standing images, as above. a Sculpture that could be viewed from all points of viewing, by moving around it. During the Middle Ages the influence of the Christian church on Western Art was to be seen in art where the human figure became more abstracted, even elongated and lacking a sense of weigh and drapery which did not reveal the body, a symbolistic display of the human body – I refer to the Jamb figures and a discussion on YouTube – Khan Academy, A brief history of representing of the body in Western Sculpture. The figures are attached to the Cathedral in Chartres, France. My readings confirm that when Christianity became the state religion in Rome, nudity was considered ‘sinful’. It seems that only during the Renaissance period nudity was truly accepted again – and it was seen as a form of art. Life models were not regularly used during this period – ancient sculpture or manikins were used. Raphael expanded his working methods by using female nude models. From 1490 onward artists began to product a wide range of new images depicting nude, partially nude, or bare-breasted women. It is also interesting that during the Renaissance that Leonardo da Vinci explored scientific questions by using his knowledge and studies of the human body to make more precise renderings of the human body. We see a juncture between science and art in these works. As an artist he established for his own purposes a clearer idea of how the human body functions and this gave him a greater knowledge of the musculature beneath the skin. Leonardo also used the theory of proportions in his drawings of the human body.

I looked at the drawings and paintings of Giotto: the figures are not stylised, not elongated and do not follow set Byzantine models. They are solidly three-dimensional, have anatomy, faces and gestures that are based on close observation and are clothed, not in swirling formalised drapery, but in garments that hang naturally and have form and weight. Although aspects of this trend in painting had already appeared in Rome in the work of Pietro Cavallini, Giotto took it so much further that he set a new standard for representational painting. The later 16th century biographer Giorgio Vasari says of him “…He made a decisive break with the …Byzantine style, and brought to life the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years.” Another interesting find is the following: “Leonardo said this was because he did not learn from masters, but drew directly from nature. It was because Giotto was an unspoiled rustic, sketching as he tended his flocks, that he became great, thought Leonardo – because nature is the true teacher.” ( The Guardian, December 2004)

Western art history carries on and with it traditions of depicting the human head and from has been challenged, developed, contemplated by many artists. We cannot escape this history of art, we need not erase this history. We need to look at other cultures and visual images of the human body. I wonder about assumptions created by Western Art History on youth, beauty and how it was driven over centuries by commercial interest and how this influenced the Western aesthetic consciousness. Artists have started challenging classical traditions of art.

My thoughts starts developing around

- When we look at art of the human figure, do we individualise and or personalise this visual experience;

- Nudity in most of human history was a natural and normal part of life – perceptions of nudity are relative within the culture where we find ourselves in;

- Is valuing the beauty of the human body a claim to civilization of a culture or society?

- Observational drawing of the human body in real life gives an artist the opportunity to analyse/ learn whilst drawing – thus developing technically and reach a point of excellence in seeing.

- Looking for beauty in art could also be explored in life drawing -The senses of beauty are as varied as the artists who approach the work. And the sense of beauty evolves over time in each artist as he or she discovers themselves through the work. ( D Maidman blog)

I like the following opinion: “Human perception of the body is so acute and knowledgeable that the smallest hint of a body can trigger recognition.”

—Jenny Saville

Acquaint myself with how the depiction of the male and female nude has changed over the centuries.

I read the following: ” The current landscape of contemporary figurative painting is particularly strong, not only due to the commercial market for it, but perhaps more so the way that artists are portraying people in response to salient topics and issues of the 21st century—from race, gender, and war, to privacy, social media, and love.” ( June 2016, Artsy.net)

In an essay dated 2002, by Amelia Jones, “Every man knows where and how beauty gives him pleasure”, Preziosi( 1998 p 375 – 390) she refers to writings of Edmund Burke, 1756 about describing a beautiful woman in her nakedness. She maintains that in the history of Western art the most dominant kinds of aesthetic judgment, ” the naked white female body has long been stages as the most consistent trope of aesthetic beauty.” During a recent visit to Barcelona I visited the Museu D’art Contemporani De Barcelona (MACBA) where a series of rooms were dedicated to experiences of art from 1929 to the present. The rooms on feminism and feminist activism (late 60’s and 70’s) caught my attention as the objectification of women and commercialised female stereotypes were addressed. Until the 1960s, art history and criticism rarely reflected anything other than the male point of view. The feminist art movement began to change this, but one of the first widely known statements of the political messages in nudity was made in 1972 by the art critic John Berger. In Ways of Seeing, he argued that female nudes reflected and reinforced the prevailing power relationship between females portrayed in art and the predominantly male audience. I enjoyed John Berger’s Ways of Seeing 1972 BBC series – part 2 on Woman nudes was particularly of interest.

Interesting art show I would like to see is the Annual Women Painting Women show, this year they added Men Painting Men. This show invites figurative artists of both sexes to submit artwork and share the beauty we see within ourselves. I read the following: “Men and women did not receive equal opportunities in nude training during the Renaissance. Female artists were not allowed access to nude models and could not participate in this part of the arts education. During this time period the study of the nude figure was something all male artists were expected to go through to become an artist of worth and to be able to create History Paintings.”

The term, The Male Glaze, was interesting point. The concept of the male gaze was first developed by the feminist film critic Laura Mulvey in the essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in which she proposes that an asymmetry of power between the sexes is a controlling force in cinema; and that the male gaze is constructed for the pleasure of the male viewer, which is deeply rooted in the ideologies and discourses of patriarchy. John Berger addressed the subject of female sexual objectification in the arts, noting that “according to usage and conventions, which are at last being questioned, but have by no means been overcome — men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. In Italian Renaissance painting, especially in the genre of the nude subject, a perceptual split arises from being both the viewer and the viewed, and from seeing one’s self through the gaze of other people.

A great article I have been looking at is; Dear Jerry: Notes on Life Drawing ( HuffingtonPost 06/05/2014, Daniel Maidman talking to art critique Jerry Saltz) Maidman has been doing life drawing classes for years – he is self taught in this figurative drawing process and has shared many blogs over the years about his work as well as his drawings. This is his take on the nakedness in figurative drawing in art: “The persistence of the figure in art from the first known art objects, down through the present, answers neither to sex nor to chance, but to spiritual necessity. We need to know one another, by means of sight. This will not become obsolete or irrelevant until the brain leaves behind its facial and body recognition circuitry, and the soul its desire for companionship and possession.”

Bibliography:

Kenneth Clarke YouTube video series: Ways of seeing

Khan Academy A brief history of representing of the body in Western Sculpture

Pepperell R., 2011, Citation: published online: Connecting art

and the brain: an artist’s perspective on visual indeterminacy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience Copyright © 2011 Pepperell (downloaded on 1 October 2018)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, April 1983, Leonardo da Vinci Anatomical drawings from the Royal Library Windsor Castle ( P 143 – 161)

Foreshortening to create a particular effect

First is a practical exercise to draw my body as I see it in a mirror, if I lounge on a couch with a mirror facing me from the foot end. The feet that are much bigger in comparison with my body is the effect called foreshortening.

Foreshortening in a figure drawing or painting affects the proportions of the limbs and the body. If you are painting a person lying on their back with their feet facing towards you, you would paint their feet larger than their head to capture the illusion of depth and three-dimensionality. In essence, foreshortening can help create drama in a painting. The artist, Dan Gheno describes his use of foreshortening as follow: “Used sparingly, line can be your most potent tool for conveying the effects of foreshortening. As one form on the model intersects and crosses over another, let your line describing the front form overlap the stroke describing the back form. As you can see in my drawing Reclining Woman, the line representing the foreground ankle overlaps the Achilles’ tendon, and the line following the edge of the knee cuts in front of the upper leg. Sometimes I like to selectively darken and/or thicken the line as it overlaps the back form, as I do here at the knee. Usually I selectively lighten the line portraying the receding form, as I did with the thigh where it passes behind the knee, before I let this line gradually darken again at the top of the leg where the thigh overcuts the stomach.”

by Dan Gheno, 1998, colored pencil, 18 x 24.

Historic and contemporary artists whose work involves the underlying structure of the body

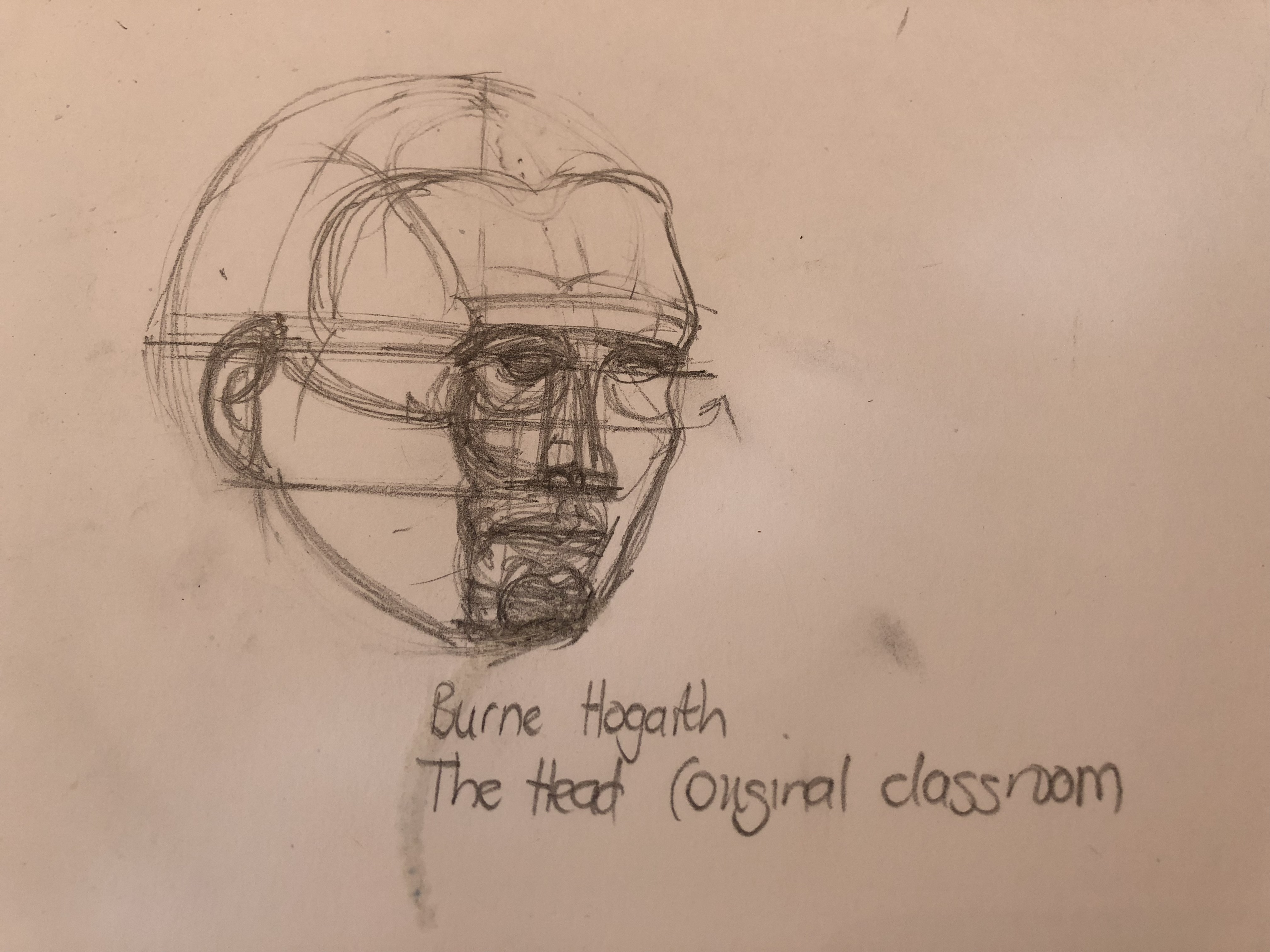

Whilst battling with my own head study, I came upon a Youtube video of a classroom demonstration drawing by Burn Hogath – he described the form of the head as egg shaped. I did the drawing in my sketchbook whilst he was doing his teaching and demonstrating.

Leonardo Da Vinci

In his Study of the Head, Da Vinci used relational measuring to confirm location: if he wanted to lock in the location of the nose, he drew a line indicating the underside of the nose that carries all the way across to see where it hit the ear. From each side of the nose he extended a line up to see where it hits the eyes and down to where it intersects the mouth, chin and neck.

The following was found in an article on Jenny Saville’s opinion about what artists can learn from the drawings of Da Vinci: “What Leonardo is so brilliant at is the three-quarter-turned head. It’s the most difficult thing you can do, to turn the

far eye a three-quarter turn, anatomically and structurally. He always chooses these sorts of poses. For one thing they give you incredible form, because of the way the light hits — you’ll get a shadow under a nose and light to the left of the mouth, so you get this beautiful flowing form. For another, because they’re challenging; I guess it shows

his mastery, that he could do any type of move and pose. There’s no one better to look at when you’re learning how to draw than Leonardo. No one can draw an eye and an

eyebrow like Leonardo. You can always tell a Leonardo by his eyebrows. He understands the ridge at the top of the eye, and that the hair sits on the top of the ridge. Usually he thins out the hair at the point of light. He always gets the sense of the skull underneath the skin. I think what I admire so greatly is this use of structure mixed with his ability

to create movement. A single line might tell you about the structure of a frozen reality, but the movement of his lines with that solid line tells you about the nature of reality, in that things are not static, they’re constantly in flux.

Louise Bourgois

In her series, À L’Infini, which consists of sixteen large etchings on paper, framed and arranged in grid there are depictions of the female body, body parts, disembodied limbs, couples – spiralling across the paper. Each sheet has the same printed image of two intersecting tube-like lines as a base, which Bourgeois added to with pencil and gouache washes. On some sheets there are traces of words written in pencil. According to the Tate website, the French title of the work, ‘À L’Infini’, translated as ‘into infinity’, is suggestive of both an unmapped expanse and a life cycle. This idea is borne out by the evocation of bodily forms across the series, which range from full figures to body parts as well as more abstract shapes and textures evocative of internal organs. Over her years of working it became clear that Bourgeois has blurred the line between printmaking and drawing. “As [Bourgeois] herself said, for her, there was no ‘rivalry’ between the mediums. Instead they allowed her to say ‘the same thing but in different ways.’ ” ( Galerie Magazine.com)

Pamela Phatsima Sunstrum

This Botswana born artist works in Johannesburg, South Africa, and through her wide workspan, of drawing, installations, stop-motions animation and performance she is trying to tell stories or respond to a narrative or mythological drive. She sees using the figure is a natural and almost necessary way of getting at that drive. Trained as a dancer, she models her figures on herself, using her own body as a vehicle for exploring existential narratives and advanced scientific and mathematical theories, while challenging conceptions of how the female has been represented in art and art history. “I’m curious about how arms can hang, how knees can bend, how a back can twist—to suggest an entire identity or history even if it’s an invented one,” she explains. “I find it fascinating that the things our ancestors were most obsessed with are the same things we as so-called advanced scientific thinkers are still obsessed with: Who are we? Where do we come from? Why are we here? How was the universe made? The figures in my work operate as carriers of these musings.” ( article in

Whilst reading through my blog before submitting my work for Assessment, I decided to add more of P Sunstrom’s recent work – I love how she captures movement in her latest work, which is on exhibition at the Zeits MOCAA Cape Town, South Africa. Below is a drawing with pencil, gouache and marble dust gesso, done on a wood panel:

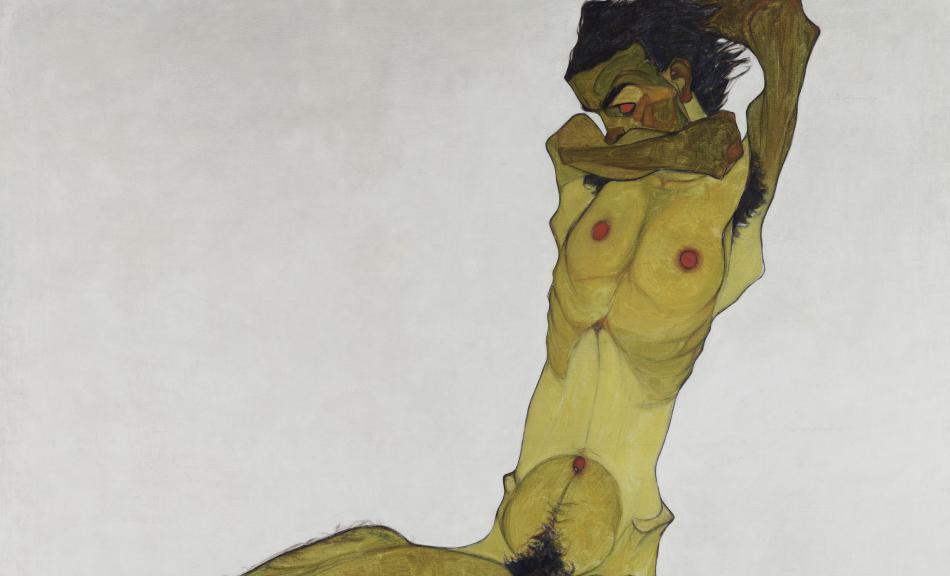

Egon Schiele

I have read opinions about Egon Schiele ( 1890 – 1918), which states that this early advocate of Expressionism was perhaps the most influential figure painter of the 20th century. This artist have explored distortion of the body in his drawings, which brings out contours and lines with sensitivity and a rawness, rather than beauty and physical completeness of the artists before him. It is also a self portrait. Parts of the body is cut off, it has no feet or hands, it almost floats on the canvas. I read that Schiele made at least 3000 drawings in his short career! This drawing was done with black chalk, water colour and gouache.

The Leopold Museum attaches the following poem by Kaffka next to this work:

“When you stand before me and regard me, what do you know of the pain that is within me, and what do I know of yours. And if I were to throw myself down on the ground before you and weep and tell you stories, what more would you know about me than you know about Hell when someone tells you that it is hot and horrible? For this reason alone, we human beings should stand before one another just as respectfully, contemplatively and lovingly as we would before the gates of Hell.”

[Franz Kafka in a letter to Oskar Pollak, 8 November 1903]

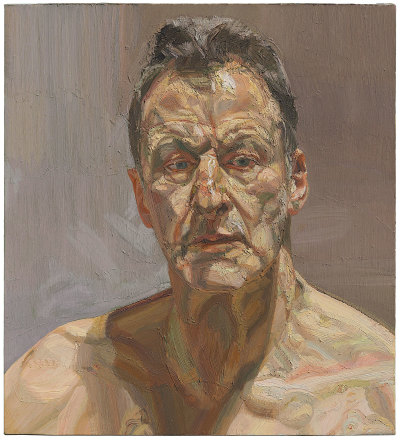

Lucian Freud ( 1922 – 2011)

A more recent artist also inspired by the Expressionist style. His nudes were graphic and discomforting. He puts me as a viewer in a place where idealised human form are challenged, and I like that. I have always been an admire of the way his paints flesh colour and his honesty in every sense of what he sees. His use of his brush and choice of colours, like greens in flesh is for me almost the same as Van Gogh’s use of Yellow.

In my readings on Freud I learned he has done many drawings and sketches in his live as an artist.

On Paper is a book that was dedicated to his drawings and the following reading was interesting to me: ” Lucian Freud claimed, ‘I would have thought I did 200 drawings to every painting in those early days. I very much prided myself on my drawing.’

Drawing became an important part of Freud’s life from the start and a famous sketchbook, “The Freud-Schuster Book”, dating back to January 1940 when Freud was in Snowdonia with Stephen Spender, has survived. So too do sketches from Freud’s life as a merchant seaman on a cargo vessel in the Atlantic in 1941. His then surreal style lent itself to illustrations and his fascination with animals, birds and fish was revealed in the famous line drawings he produced for Nicholas Moore’s book of poems, “The Glass Tower” (1944). “On Paper” charts the works on paper, including the etchings, over his entire career. It includes the formative early work, the sketches in preparation for painting his masterpiece, “Large Interior W11” (after Watteau) (1983)”

Willem de Kooning

I was inspired to look at his painting Woman 3, 1952-53

Being an abstract painting, I had to look for structure, shape, as this artist for sure breaks the rules! The legs and how they are placed at a “perspectival triangle’ to fall towards her lap is in my view use of structure and space. The drawing is 2 dimensional, is has weight and shape and shows a female figure who dominates the space. The female figure was a theme to which de Kooning returned repeatedly. They are often depicted in an almost graffiti style, with gigantic eyes, massive breasts, toothy smiles and claw like hands set against colorful layers of paint.

Heidi Hahn b1982

Hahn has been painting figuratively since her undergrad years at Cooper Union, but only recently gained wide acclaim, following a solo show at Jack Hanley Gallery in New York.  For her recent series “I Saw the Future and It Reminded Me of You,” she focused on pattern making; each painting, of one or two girls, was copiously dotted with tiny flowers. She is quoted as saying about this painting the following: “The repetition of the flower patterns was to adhere to and anxiety-making, but I knew I wanted to paint within that anxiety because the content called for it.”

For her recent series “I Saw the Future and It Reminded Me of You,” she focused on pattern making; each painting, of one or two girls, was copiously dotted with tiny flowers. She is quoted as saying about this painting the following: “The repetition of the flower patterns was to adhere to and anxiety-making, but I knew I wanted to paint within that anxiety because the content called for it.”

Historic and contemporary artists who use the face in different ways

I am contemplating the idea that the face serves as a field of ‘signs’, which, rightly read, could be used to determine the inner nature of the soul behind the face. A number of leading Baroque artists, including Bernini and Rembrandt undertook intense studies of faces in extremis, both as cameos in their own right and to provide raw material for expressions in narrative compositions. “The faces are just a symbol needed to express and possibly reflect the viewer’s own soul. The soul itself is a deeply buried treasure. It is something we all have, but that we rarely visit.” – Johan Van Mullem

Graham Little: These pictures are created with pencil and gouache on paper which makes me look at this artist as a person who spends probably hours rendering these drawings so that they almost look like baroque paintings. When I first looked at his works, all these faces of the women reminded me of selfies and how I see people use apps to soften their looks – to a point of softness that makes me sure the pictures are “photoshopped”. It challenges the image of woman in my opinion – introspective??? to be seen as perfectly manicured???? I find value by him using drawing materials to create expression. It inspires me to without having to give work a title – the viewer can understand the emotions depicted. It reminds me of the first exercises in this course – feeling and expression with lines, marks and abstract shape. The details of colour and patterns in the clothing is very decorative and his draftsmanship is shown. I read he uses models from old fashion magazines, yet these anonymous women are in everyday situations, not real models. Can it be that he is playing with the women being a model in society – adapting, by dressing the part? I am also thinking about the work of Degas – pastels of women, mostly prostitutes, but also anonymous

Elizabeth Peyton:pictures are painted in oil or watercolour. As a young artist she loved Van Dyck and this preference to paint a particular person in a particular place. For a time, most of her portraits were of men, famous superstars. In interviews, she seems to imply it is not the beauty or the talent of famous people that mesmerises her, but their rebellious dismissal of societal constraints. Her subjects are those musicians – like Jarvis Cocker, Kurt Cobain, – who, arguably, remain true to themselves. What I found really surprising is the size of her works, often no more than 11in high. Is the deliberately bringing these larger-than-life characters down from their pedestals – is the “lesson” not to society who put people on pedestals, when all people want to do is do their best? Her portraits are intimate and relate to her friends and heroes saying something about a world in which our peers and icons seamlessly coexist. It is almost as if the wants the viewer of her work to see whom she admires. In an interview with The Believer, October 2013, I read the following words between the interviewer and the artist: “Another thing I like about your work is your three-quarter views and profiles. I like looking at people in profile. Elizabeth Peyton : Oh, thanks, so do I. There’s some great Oscar Wilde quote about profiles… People are so different from their profiles. It contains them in a totally different way. ” Then I found this to ponder about: ” That’s something I’m constantly thinking about painting, because when you’re painting something that is representational, that’s not the end. Describing is no end or beginning. ”

Other comments on her work:” Her art, as Ronald Jones, her former employer, wrote some years later, was “a revival of idealism, and a revolt from reason.” Peyton works in an abstract Expressionist style -she apply her colours in broad, vigorous brushstrokes and allow them to drip in places – all this on small surfaces!

Kehinde Wiley

This black artist paint portraits with a refreshing look – he studied the old masters, know his art history, but uses to persons of colour in his Baroque European paintings. He recently was commissioned to paint the former president of the USA.

Research artists self-portraits

The work of Tracey Emin’s self portraits is often referred to as confessional, for she uses her own personal history as the subject for her artwork. She has used her own body as medium in self-portraits and performances. Her artworks enact self-mapping and self-commemorating through the possible healing and spiritual aspect of art.

Her work is very expressive and one can see the fast marks/drawing as in the print above and below.

Her work is very expressive and one can see the fast marks/drawing as in the print above and below.

Rembrandt 1606-1669 He was an accomplished portrait painter; it seems he depicted himself in approximately forty to fifty paintings, about thirty-two etchings, and seven drawings. In a 1961 book, art historian Manuel Gasser wrote, “Over the years, Rembrandt’s self-portraits increasingly became a means for gaining self-knowledge, and in the end took the form of an interior dialogue: a lonely old man communicating with himself while he painted.” In an influential 1948 monograph on the artist, Jacob Rosenberg wrote of the ceaseless and unsparing observation which [Rembrandt’s self-portraits] reflect, showing a gradual change from outward description and characterisation to the most penetrating self-analysis and self-contemplation. … Rembrandt seems to have felt that he had to know himself if he wished to penetrate the problem of man’s inner life.

Albrech Durer – a painting done in 1498 in oil shows the artist as a gentleman with a cold and penetrating gaze. Durer uses vertical and horizontal lines in this very detailed painting, which hangs in the Museo del Prado

Antony Gormley: Using his own body as subject, tool, and material, – the “found object”. He has revitalized the human image in sculpture through a radical investigation of the body as a place of memory and transformation. Since 1990, he has expanded his concern with the human condition to explore the collective body and the relationship between self and other in large-scale installations in public spaces. The nudity of Gormley’s figures contrasts with the expected conventions of city life, suggesting a stripped-down, elemental existence. Their often seemingly-precarious placement on the ledges of tall buildings offers multiple readings: perched observatory, potential self-harm, the perceived power of height. He said the following of these works: ‘The installation connects the palpable, the perceivable and the imaginable, creating a relational field in which the passer-by as well as the aware viewer is implied in a matrix of looking and being looked at.’ But why doesn’t he use models? ‘I’ve said this again and again – I think there’s no point in making another body when I have one already. I want the most direct translation from living to art. And this is the one bit of the material world that I am actually inside and that I am able to work on from the other side of appearance.’

The following was found on the TATE website: “Art is the means by which we communicate what it feels like to be alive….Making beautiful things for everyday use is a wonderful thing to do – making life flow more easily – but art confronts life, allowing it to stop and perhaps change direction – they are completely different. ” Antony Gormley

Osmond, Susan Fegley, 2000 Rembrandt’s Self-Portraits published in The Arts, downloaded form worldandi.com/specialreport/rembrandt/rembrandt.html on 8/10/2018

Klimt and Schiele

In a recent newspaper I read and interesting article on a drawing exhibition at the London Royal Academy, where rare works on paper celebrated erotic works by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele: ” Viennese figures exposed” , written by Jackie Wullshlager. The friendship between the two artists, which started when Schiele was and 20-year old, lead to Schiele taking Klimt as his guide to built on his achievement as a psychological portraitist and symbolist. Both these artists did a lot of drawings, thereby exploring new ideas of modernity, subjectivity and the erotic. The self portrait below shows beautiful line and colour.

I found the following on the website of the Leopold Museum: “I can paint and draw. There is no self-portrait of myself. I am not interested in my own person – more in other people, females. […] I paint day by day from morning to night – figurative paintings and landscapes, less often portraits. Already when I should write a simple letter I get frightened like of imminent seasickness. Those who want to know more about me shall observingly regard my paintings, and try to realize who I am and what I want.“ G Klimt.

In the above grotesque and eerie self-depiction emerged in connection with the large format painting »The Hermits«. Schiele adopts the head posture and the related straddled fingers. The series of expressive self-portraits of the year 1912 is continued in 1914, when Schiele had Anton Josef Trčka take photographs of himself. Each photograph is consciously constructed and plays effectively with eccentric gesture and facial expression.

In the above grotesque and eerie self-depiction emerged in connection with the large format painting »The Hermits«. Schiele adopts the head posture and the related straddled fingers. The series of expressive self-portraits of the year 1912 is continued in 1914, when Schiele had Anton Josef Trčka take photographs of himself. Each photograph is consciously constructed and plays effectively with eccentric gesture and facial expression.

I just had to present the following painting by Schiele here as well; being that of him and Klimt! A honest look into severe tiredness and the ‘unconscious mind” to me. It brings forward inner states of human beings – anxiety, fear?

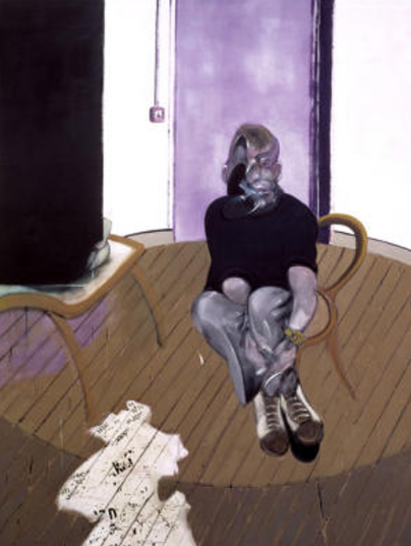

Bacon

In his self portraits, I see the movement of the head and face as what he tried to capture.

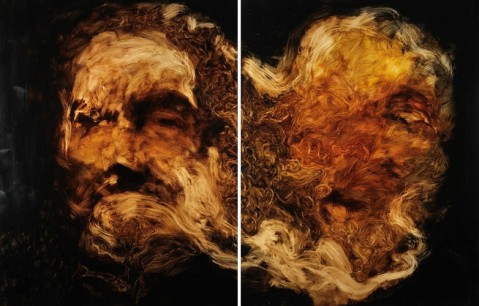

Johan van Mullem ( 1959 -) : This Belgium artist seeks to investigate ‘a visual exploration of the mind as a captive of the body’, and portraiture identifies the category of his work but not the expressionist application of his rich colour palette, in ink on board. Faces are glimpsed through swirls of reds and golds, in form and colour that are reminiscent of Rembrandt’s later works. The artist’s drawings reveal a pattern of character, building faces without creating a particular identity. Van Mullem does not use a live model to draw from and every work is the result of his imagination. The bold canvases are arresting in their emotional, luminous portraiture—that is, if you could consider the faceless figure that emerge from his canvases as portraits. ( Cassone Art.com)

Cristina Troufa

This artist uses her own image in autobiographical paintings to explore her life and spiritual beliefs. She is Portuguese born and says the following about her figurative work: “The theme of my work is about my life, about myself and my beliefs. I explore in my work the self-representation in the looking for my inner self, my self-portrait. ” I have been following her work over the last 5 years and appreciate her reflective style – an exploration of identity and self. Rarely does a subject gaze out from the canvas in her paintings; rather, viewers are invited to peer upon the subjects as if catching a glimpse of something they aren’t supposed to see. In the intimate moments, we watch as young girls investigate who they are both as individuals and within a larger group.

Interesting reading I found in a New York Times Style magazine on why portrait painting, that almost died out in the last century, are ‘back in fashion’ with artists and audiences. Interesting ideas around truth and facts, which is challenged by the current trends in social media and an institutional urgency to speak to a more diverse audience with painting that depicts the black community, the Asian-American experience, the Latino face, to attract the various people who had been excluded from the museum by remaking the history of figurative painting, this time with colour. I quote: “As we assess the various power structures that landed us here, it is stabilising and reassuring to look at the work of an artist who is clearly in control of her craft, who is able to depict a reality that is material and grounded in recognition — of seeing, in the Facebook age, a painting that looks like who it is meant to.”

Looking at artists’ self-portraits I see a strong move towards realism and not idealism. Artists are vulnerable, vulgar, expressive, challenging, explorative, sexual, communicable, in these expressions. These expressions are not always their own truth, but a way to deal with or bring to the open conscious and unconscious realities.