CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVE

Exercise 1.2. Before and after

Reading point

Link 31 refers to the last part of the text where James Elkins discusses ‘The place of Narrative in Contemporary Art.

The essay is in two parts: the first is a survey of representations of time in art; it is similar to the first part of the essay on space and form posted on the same website. The second part of the essay surveys the current possibilities of narrative in visual art; it is similar to the second part of the essay on space and form.

James Elkins argues that the story of modernism and postmodernism is almost always told in terms of four narratives. Works of art are either seen as modern or postmodern or praised for their technical skill or because of the politics, they appear to embody. These are master narratives of contemporary criticism, and each leads to a different understanding of what art is and does.

I am reminded of what I read about Phyllida Barlow and how it resonated with my own making process: “Barlow’s physically impressive and materially insistent sculptures ask questions about our relationship to objects, and about objects’ relationships to us. Slipping between different registers of form and meaning as we try to understand them, her sculptures are like things caught in the process of becoming other things, things we might have seen before or may see in the future.” (Hanjte Cantz). My mind goes to how I think about art and if I am asked how my making connects with how I understand my own art-making. I ask myself, what happens in my making that possibly does not happen in my thinking or even writing about this process. It also brings in how I consider the viewer/audience and how they understand or experience the work. (As I am writing this blog I consider my tutor and other readers/students, or assessors such as the time of assessment.

I added this part later (19 November 2021) I was reading about artists and mushrooms and came upon a work by Andy Warhol. It is a film about eating a mushroom and apparently, he shot nine 3 minute rolls of film which he assembled out of sequence so that there is no direct relation between the time spent eating the mushroom and how much of it is left. The viewer can look at somebody eating. It seems that how much is eaten at any one point in time is irrelevant. The focus is on the image of the man (the painter Robert Indiana) who is eating, and not the narrative.

Method

I want to consider the dress as a stand-in for a body. I think about the artists I have looked at and I find my ideas wander to the young Infanta in the Las Meninas painting. Reasons might be the performative aspects I see in the work, but I also think there is an opportunity to consider how painting explores the relationship among the viewer, reality, and illusion, or mystery. The painter did not leave a single word behind to give any explanation of why and how he did this work. Many narratives about how and why are available in art history and fiction. I found that my research took me to look at some of these narratives, I want to apply my imagination and take creative liberty in putting together my own narrative. ( I have added some of this at the end of this blog writing after my own project is shown and discussed.) We do not know why this painting was commissioned, I read the painting was only cataloged in the royal collection in 1666 as ‘La Familia de Felipe IV‘. Then later it was called ‘The Empress with her Ladies and a Dwarf’, then ‘Infanta María Teresa’ (by mistake they thought at the time it was a portrait of the daughter of Felipe IV from his first marriage with Isabel de Borbón). Finally, in 1843 the Prado decided to call it Les Meninas.

I start to make and gather images and stories about the Infanta and the time she lived in : some made, others found and others created by appropriation and manipulation. My idea is to use these as protagonists in my story.

For the purposes of creating a narrative, I decided to go with a storyline around some moments before and after the young Infanta, the royals, and/or some of the household members are passing through Velazques’s studio to get a peek at him painting a portrait of the Infanta and only heiress to the throne.

She is very young and used to the attention and support of servants in this special household.

How does it feel to be in this seemingly heavy dress? I read that kids up to 6years in those times in Spain dressed the same – no gender differences were shown in clothes. Kids also dressed like adults – so here we have a little girl dressed as an adult (woman) and below is her father as a very young boy. Did he know that he would be the future King?

I am thinking about interpretation, but then I feel free – I can create my own narrative for this exercise. As the story could also be different; It could be that the Infanta is the one who has stopped by to watch her royal parents sitting for the court painter. By now I see spontaneous ‘movement’ in the painting – the man in the door could be coming or going, is he opening or closing the drapes? Velazques is in action, putting paint on his brush to work onto the big canvas, the Infanta just had, or will be taking a sip from the cup. The dog is being kicked or pushed to move/awake by the little boy and will move shortly. This takes me to how I have to think about the exercise as, before and after. Is it important what happened? Is it why Velazquez made this painting? Is it about that moment in time?

I am completely aware that Velazquez has painted this work with the idea that there is not just one reading of a painting. He certainly constructed the work with a lot of thought in terms of the size, color, subject/object, use of perspective, space, and light. I am not sure it would have been like if we use a photo to capture a moment of reality I think there was some construction, even a lot, like the use of mirrors, doors, and people. Somewhere I came upon these words: “We must always remember, however, that the comparison of literature and painting is imperfect since it is based on an analogy and is not an identity”. Is there even a linear structure in this work? But then again people go back to this work, and always walk away with new interpretations, it is not as if one stands in front of the work and immediately ‘get it’, one needs some form of contemplation and by looking more intensely one see more happening in the scene, recognize certain people. One also needs to be aware of the role of interpretation, a power, which can be subjective and belongs to each and every viewer, and could be the final ‘constructor’ of narrative.

The creation of how the painting came about is the story I would like the viewer to reconsider. It continues to capture others, famous artists such as Goya, Picasso, and Dali made their paintings after this work as a form of inspiration and interpretation. I learned that Dali was captured by the light in this work. Picasso made 58 works from studying the Las Meninas. I saw these works in Museo Picasso in Barcelona in 2018. I think these works by Picasso can be seen as performing a comprehensive analysis, reinterpreting, and recreating (appropriation) of the work done by Velasquez in 1656.

I learn on the Tate website that Picasso was involved in the Amnesty for Spain campaign to free Spanish Republicans still imprisoned eighteen years after the end of the Spanish Civil War, therefor his works could also be seen as a bitter satire. It is about his reality and revealing Franco’s careful and cynical orchestration of his image in the grand tradition of Philip II of Spain (1527–1598), the great Habsburg King. In these works, Picasso transforms the original meaning of the Velázquez into a cruel indictment of Franco’s dictatorship and his royalist aspirations (to be succeeded by a member of the Spanish Monarchy): ceiling bosses become grotesque hooks for the suspension of torture victims, and the painter becomes a figure from the Inquisition. The maid in the foreground has Franco’s mustache. The many variations on the figure of the Infanta make pointed reference to the traditional Royalist ‘coming out’. Don Juan’s daughter, the Infanta Maria Pilar, took place in October 1954 at the Hotel Parque in Estoril, Portugal, where a spectacular ball was held.

It seems the history of King Philip IV is quite different in that he was a big collector of arts and culture, compared to his father and grandfather who were very ego-driven and harsh rulers. On the Prado Museum website, I read about his collection of art, that he commissioned artists, such as Claude Lorrain, Nicholas Poussin, Jan Both, Gaspart Dughet to participate in a series of landscapes (24 works). In Madrid, the pictures were installed in a room known as the “Landscape Gallery” located in the west wing of the Buen Retiro. It seems that at this time, the theatre was considered one of the most important leisure activities.

I learn that at this time, Spain was ruling over the Netherlands, Portugal, Western Europe, South Americas, Philippines and areas in South East Asia. Alliances through marriage were a well-known position for the Monarchs and their hegemony in Europe. My own story link with the Netherlands when they started finding new trade routes for the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and started an Outpost at the point of Africa, the Cape of Goodhope, in 1652. Cape Town as it is called today is also my birth town. The outpost was intended to supply VOC ships on their way to Asia with fresh fruits, vegetables, meat and to enable sailors wearied by the sea to recuperate. (To remind of the story around the young infanta, at this stage she was 2 years old)Dutch expansion into the country soon started.

My father is of German descent and my mother is of French. I was born at the height of the Apartheid regime and cannot escape this part of my own identity as a white South African, who benefited from the political ruling of the day, and a history of colonialism.

I consider how upbringing and opportunities for women changed since the life of the little infanta and my own. I am aware that she was not the longed-for boy, a brother was born much later, he died, but then Charles II was born to be the King. Her young mother as a woman was obliged to have sons as future heirs to the King, despite the close consanguinity of the couple. (they were first cousins) I read that she never had serious health problems and was seen as an attractive person with a lively character. She grew up in the Queen’s chamber in the Royal Alcazar of Madrid, where she received a good education but was also brought up in accordance with the strict etiquette of the Madrid court, surrounded by maids and servants. Apparently, in his private letters, King Philip IV of Spain called her “my joy”.

I cannot help to consider how a dress is still important around social standing and the role of privilege, here the protagonist is the heir to the Spanish throne. I think ostentation was seemingly admirable in the Court of the King, and I cannot help but think of novels I have read (even Hollywood movies) which would describe this as the normative within social classes – the contemporary thing for that time? How do we deal with these effects today? Does something similar still happen today?

My ideas are built around this as an inspiration. I will look at the little Infanta, who was only 5 years old at the making of this work. The little girl in the center, the artist with a brush, and the mirror in the background offer us many angles on history and culture. The infanta was called Margeret Theresa. She was born in 1651 and was betrothed to her maternal uncle, Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, as a young child, at the age of nine. At the age of fifteen, she married him. (As a politician and mother of an heir). She died at the age of 21 as a result of the aftermath of the difficult delivery of her fourth daughter. It seems that many of the portraits of the Infanta, painted by Velázquez and his successor as court painter, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo, were intended for Leopold I and were sent to his court in Vienna. In the images we have seen of her, she is dressed like the rest of the female adults. It is interesting how small and almost illuminated she looks.

The big dress captivates me, and I then read about the little red jar which she is holding in her hand, or is it presented to her on a tray? According to The Met website and other readings, the jar is called a Bucaro. I came upon the work of artist, Peter van Toth, who suggests that while there is some evidence that eating the pottery would have the desired effect, he also refers to some undesired ones, and alludes that it could alter a woman’s menstrual cycle and that there is testimony that the act of geophagy (‘earth eating’) and that is could be hallucinogenic (induced euphoria and lightheadedness). He shares the words of a Spanish poet, and contemporary of Velázquez, Lope de Vega, : “Niña de color quebrado / O tienes amores o comes barro” translated into English: “Girl of sallow colour, you’re either in love or you eat clay’).”

These ideas were also shared in a BBC online article by Kelly Grovier in October 2020. I understood from this article that Grovier was reacting on a book written by Laura Cumming, The Vanishing Man: In Pursuit of Velázquez. Here the writer and art critic reflects on Las Meninas’s remarkable ability to present a precise vision of reality while at the same time remaining open a mystery.

Infanta Margarita in blue .

1659. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Vienna.

Introduction: It was the year 1656 in a castle in Spain when this story started. The Infanta who earlier in the day was dressed by her attendants for a session with the court painter, Velazques somewhere in the big castle, was leaving his studio. Her dress was decided on by her mother and was hanging ready for her to wear for these sessions. I cannot tell you how many sessions she had to sit in, but the dress was big and heavy and even though the Meninas was helping her to get dressed it was not a comfortable dress, I think she did not like it very much, as she had to stand whilst the painting was being made. It was just so uncomfortable.

See the painting below.

Hypertext would have worked here: This painting was found and belongs to the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. On their digital website, the museum states: “The portrait shows the five-year-old Infanta in a severe pose as if an adult. The imperial emissary also praises her good behavior in the letter he sent with the portrait to Vienna. At the same time, Velázquez painted the many figured portrait “Las Meninas” (Madrid, Prado), in which the small Infanta, standing in the midst of her royal court, reveals more of her individuality.” One can see it is the same dress, her hair is curled and a bow is in it, and she looks very much the same age as in Las Meninas. The provenance note at Kunsthisorisches Museum, Vienna, states the following on above image: Probably sent to the imperial court in Vienna shortly after its creation; at an unknown time transferred to Prague Castle; in 1876 transferred from Prague to the imperial picture gallery;

Development of story: The painting session could not end sooner and the Infanta will shortly accompany her mother for lunch, with the dog running along, like as her Meninas, all following her. Velazquez will stay behind and consider his work for the day. He also hopes this painting will be finished soon as the little girl was restless and had to be soothed and bribed to stand while he painted her. The little red búcaro with sweet water was a concern for her parents, as it could damage her teeth, and it was offered to her regularly during these sessions. Velázquez was painting in the Pieza Principal (main room) of the palace. King Philip was sitting on a chair watching Velázquez at work. I can imagine the high ceilings and scale of the room from the Las Meninas painting. The red curtain opened and the Queen walked in to inquire if the Infanta was ready for lunch. See the image below.

Move forward in time: I want to consider a different time and place. Below is a photo of myself at age 5/6years, dressed in a wide, short dress, the fashion of the day, among my friends and a moment caught on camera. Earlier that day we took part in a children’s radio program and this photo was taken in the recording studio. I would think that I choose the dress I was wearing for this day of recording in the Radio station’s studios. Afterward, we would stop for ice cream and then maybe spend some time running and playing on the beach before my mom would drive us home, drop off some of my friends (parents took turns to take us Saturday mornings) I was the firstborn child of my parent’s marriage and have a sister three years younger than me. I believe due to our social circumstances a boy was not expected to be achieved – no pressure due to political, social or economic reasons. I am well aware of the fact that my father’s younger brother had a son born into their family and that in that way the family name could continue, unfortunately, he had two girls in his marriage. A funny little incident my 90-year-old dad reminded me of recently: When asked on this radio program what my name was, I answered the following, ‘Karen Kuhn Carolina Wilhelmina‘ – my birthnames clearly made no sense to me.

So much different than in the house, no! the palace of King Philip IV. Our little infanta, Margaret Theresa, knew exactly everything about her family tree, the need for the longed-for boy to be the heir to her aging father, and the importance of this to the role of the Monarchy in Spain. A heavy burden upon this little girl.

Meantime in my world fashion of the day (1960’s) was considered by an online search for patterns for clothing, as the chance is very high that my mother made my dress. See the images below.

My paintings of the little infanta become sad and heavy with the burdens of her life.

At the age of nine, she was betrothed to her uncle, Emperor Leopold I of Habsburg. He was her mother’s brother, and at the age of fifteen, she married him (As a politician and mother of an heir). She died at the age of 21 as a result of the aftermath of the difficult delivery of her fourth daughter.

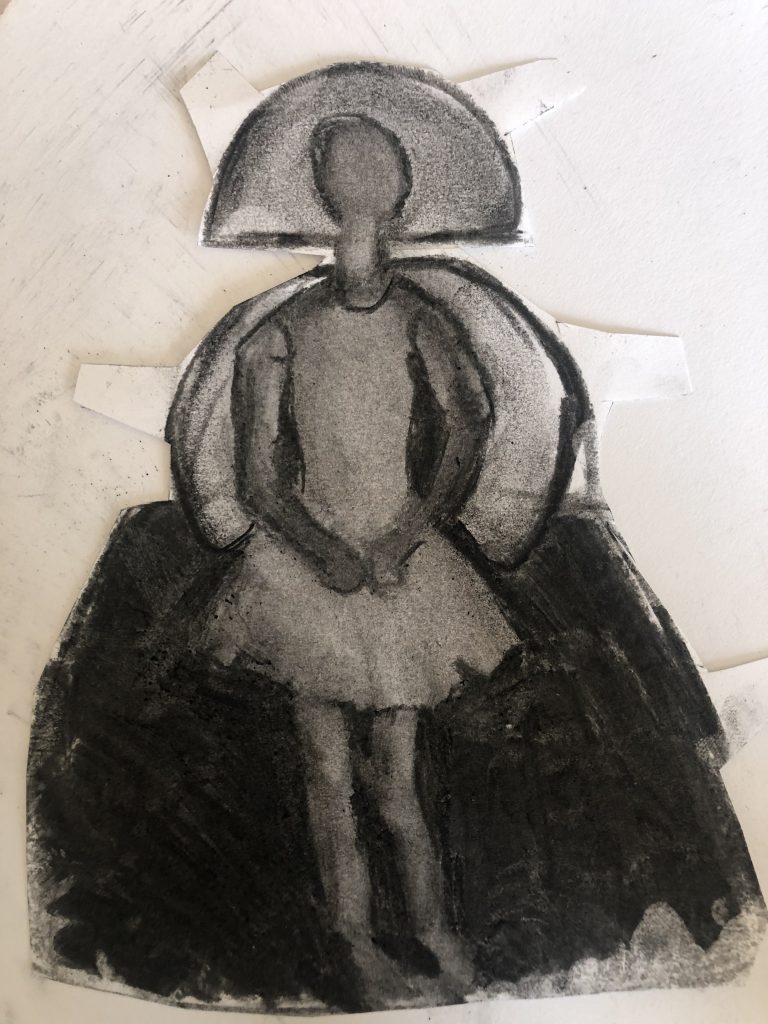

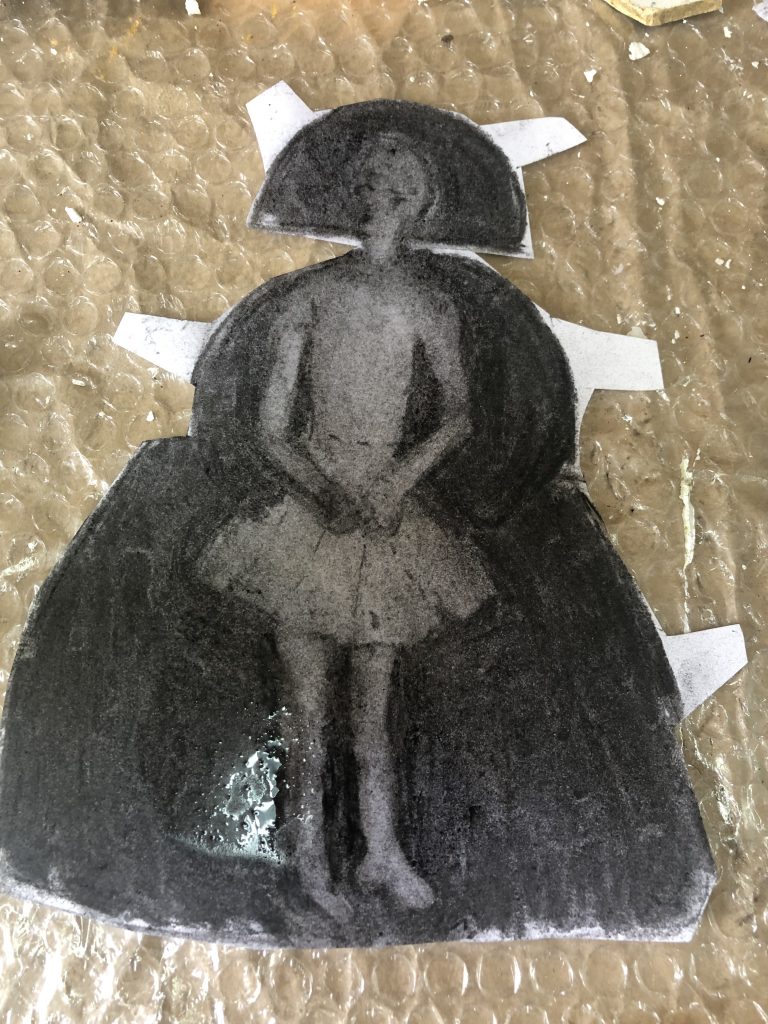

Using a free app to put the image of my younger self “inside” my painted Infanta/Meninas dress. It is clear that the dress is too long and that the body had to be lifted to fill the dress.

An average girl of 5years is 107.9cm (42.5”) tall and could weigh 17.9 kg (39.5 lb) Interesting that there is not much difference compared to boys (google growth chart percentiles were compared)

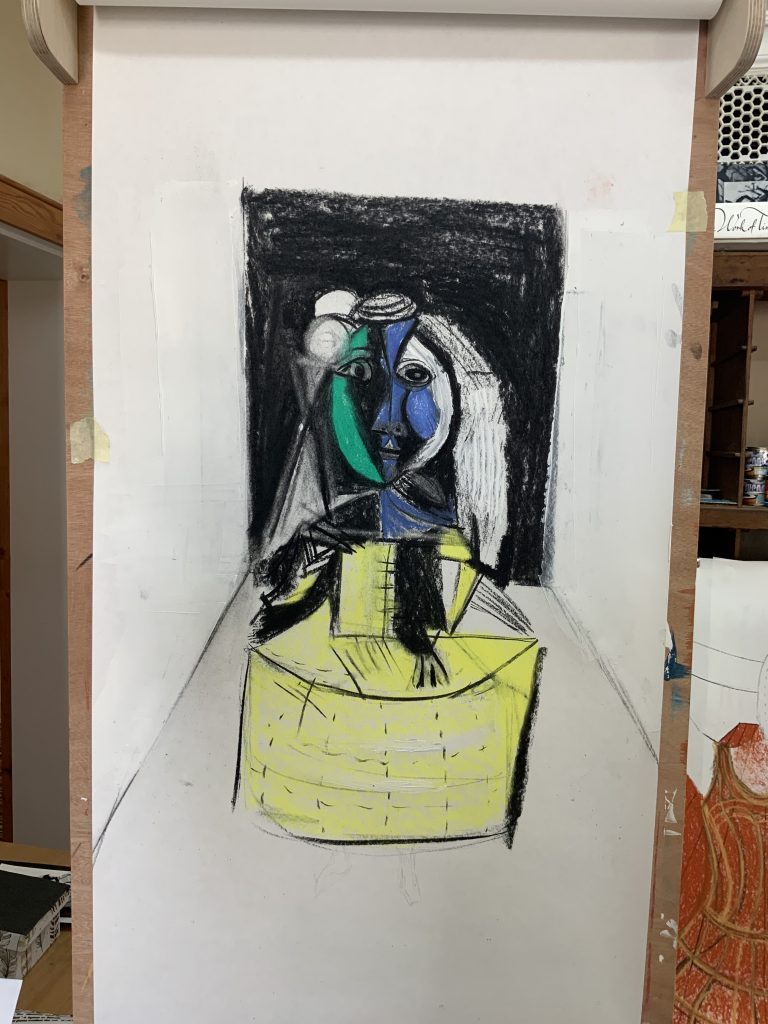

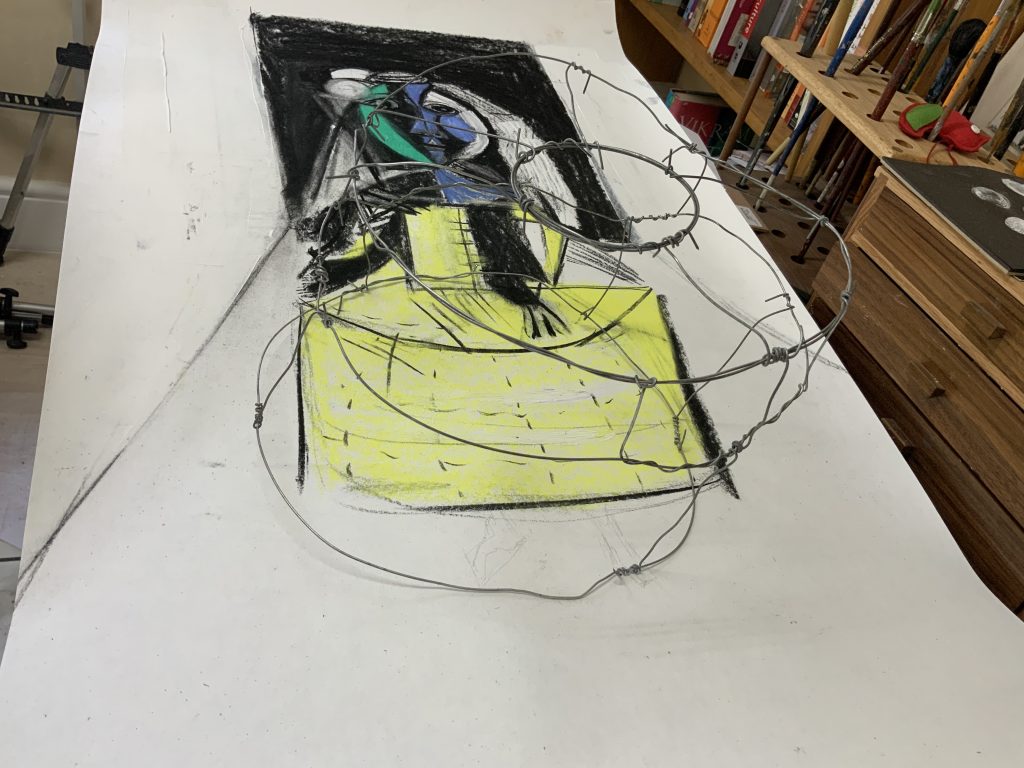

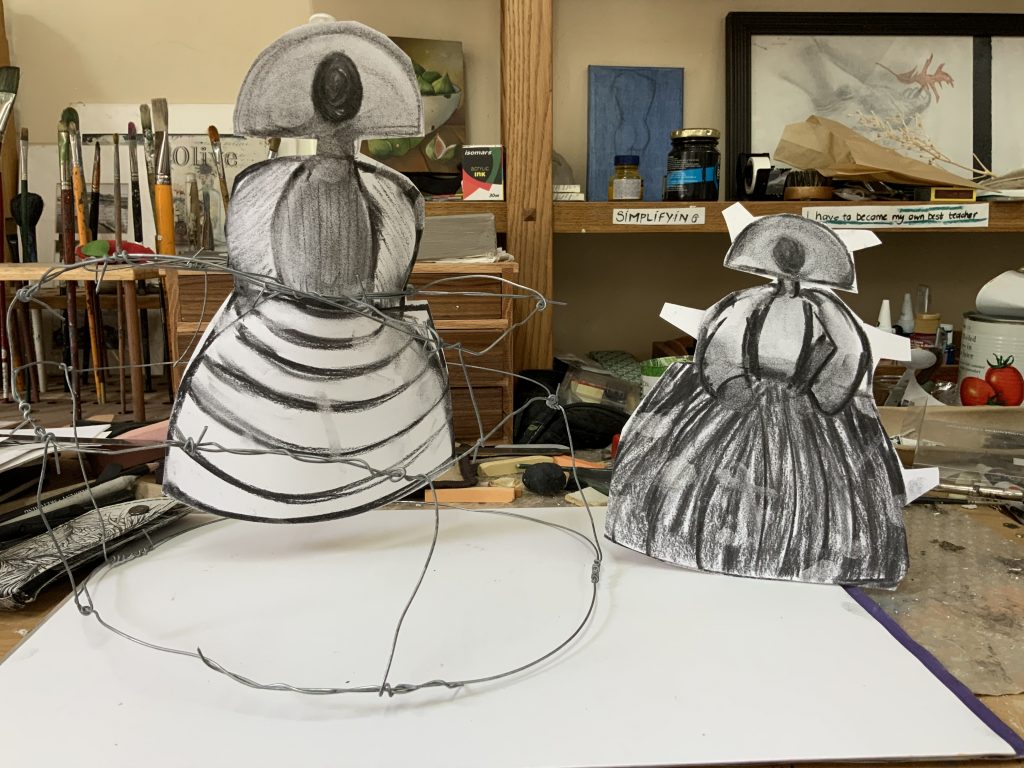

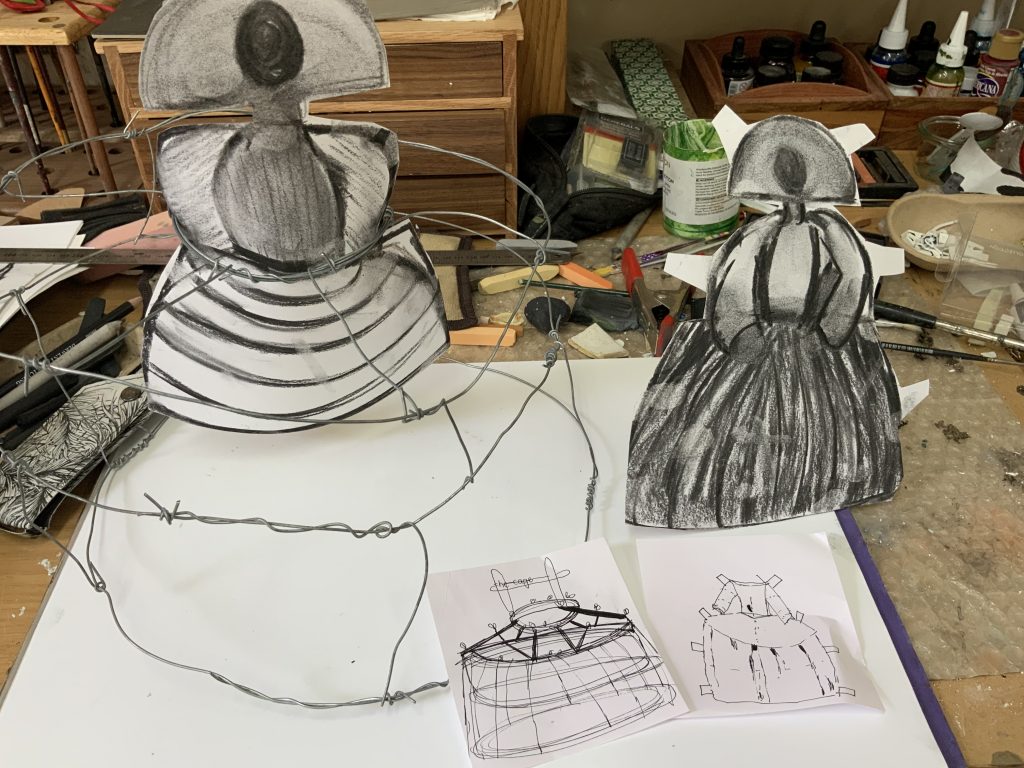

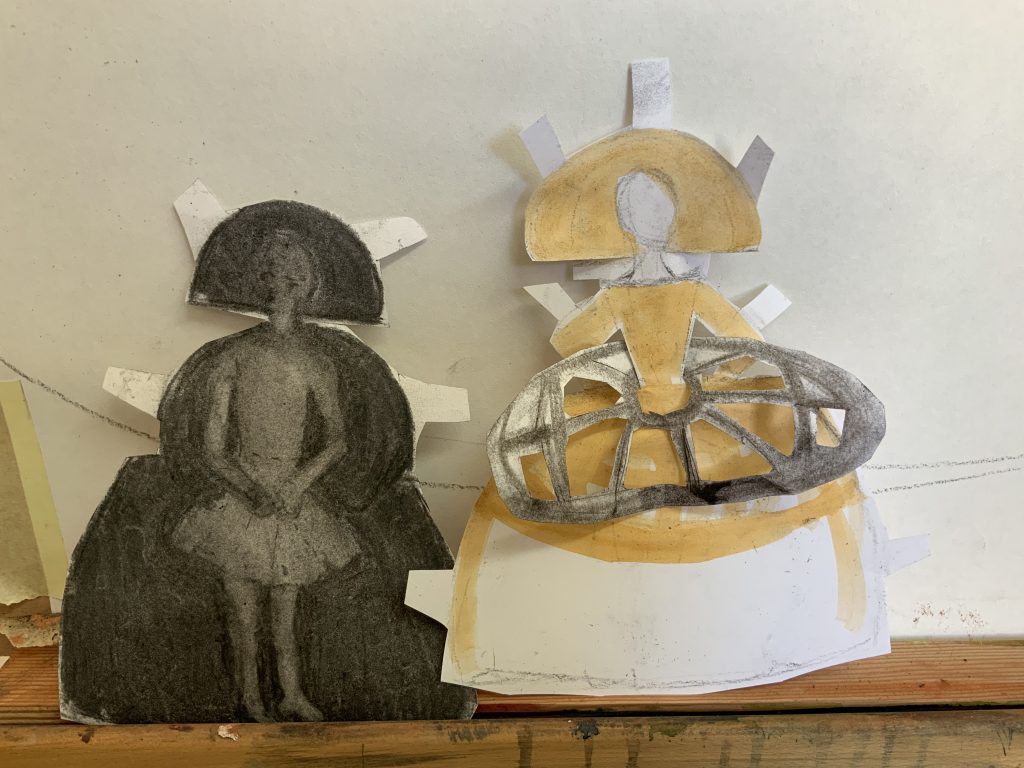

Rachel Baes, like other Surrealist woman painters, opposed the image of women as muses, dream beings, and passive objects. Below is my interpretation, after Picasso and influenced by earlier research of the surrealist painter, Rachel Baes. I worked with charcoal and soft pastels onto wallpaper paper. In my mind it was not easy to dress as the expectation in the Court was, being told what and when and how always pleasing others. I do think of her as a puppet or a little paper doll. I think about control in a way I see the link with the work of surrealist painter, Rachel Baes, the objectification of the female and feminine cultural ideas, such a dress, should feel being captivated by the female role/perception/expectation in society. I learned that the use of mannequin is a widely used fetish. I believe Rachel Baes commented on this in her work The Polka.

I think about Hollywood/Social media focus on rich/famous women and girls dreaming about fairy tale lives,( think about the wedding dress real-life shows I see on our local TV ) influence of fashion and culture ….. something about this tension between the real and the idealized. I think it is a feminist theme in so much as women were portrayed over centuries, mostly by male artists.

I used the ‘paper doll’ and erased myself into/onto the image. I love how charcoal as a drawing tool can work with erasure as a trace of a drawing.

Body modification is a way to obtain a fashionable silhouette: it has been used over centuries to fit the ideologies and practicalities of each time period. Fashion has agency and according to Engel (2019), it offered “another way in which the female body was presented to society. Throughout the eighteenth century, hoops shaped not only the female silhouette but also how people within society viewed themselves and each other.” How does this experience inform identity? Looking at the Infanta Margaret Theresa, at this age, she is the heir to the King. Did this make her so see herself as a precious child/girl, or was it a burden? Did she have friends in the palace to play with? What did her toys look like?

Dresscode of the court: I read about the special shoes they wore with the guardainfante, called chopines. It had wooden or cork soles, which helped to elongate the figure. The guardainfante or wide-hipped farthingale was outlawed in Spain in 1639 for supposedly hiding illicit pregnancies and promoting unchaste behavior in women, but the King’s wife and family kept wearing it till around 1670. (Wunder, 2015) In this period the dresses grew larger in size and popularity. It is clear that these garments tended to reduce movement and confine bodies, creating a rigid silhouette. It comes from the Spanish words for “guard” and “infant,” meaning “infant-guarder.” The effect was to widen the silhouette at the hips to an unnatural degree which, in contrast, minimized the waist. I do not want to make opinions about fashion, taste, and affluence, as clearly, this played a big role in how everybody in this artwork was dressed. It is not sure if she wore these shoes, but to me, she does look a bit elevated, so in my story, little platform shoes were on her feet.

Clothing and fashion of the day come to mind – the ‘guardianfante’ was presumably of a heavy brocade type fabric. I understand that clothing in this situation is loaded with political meaning. She is the daughter of the king. The guardainfante was made with wooden hoops, wire or wicker joined together with ribbons or ropes and was completed in the upper part with wicker to emphasize the hips. This “guardainfante” was also covered with petticoats, sometimes padded with wool to round the hips and on the skirt, the outer skirt was called a “basquiña”. At the top of this “guardainfante”, the feminine silhouette was modeled with the stays, a garment armed with corset stays, whose purpose was to enhance the feminine attributes. This intention emerged from the ideals of beauty in the sixteenth century and gave birth to the so-called chest cardboard, the origin of the different corsets that have appeared in Western fashion throughout history.

If one wants to imagine the comfort level of wearing this stiff and heavy attire, I cannot imagine a little girl moving around in such a dress – I do hope she only wore it for the sessions with the painter. I can just imagine the effort to get her into the dress – something she could not do on her own, but also in her position was not supposed to do on her own.

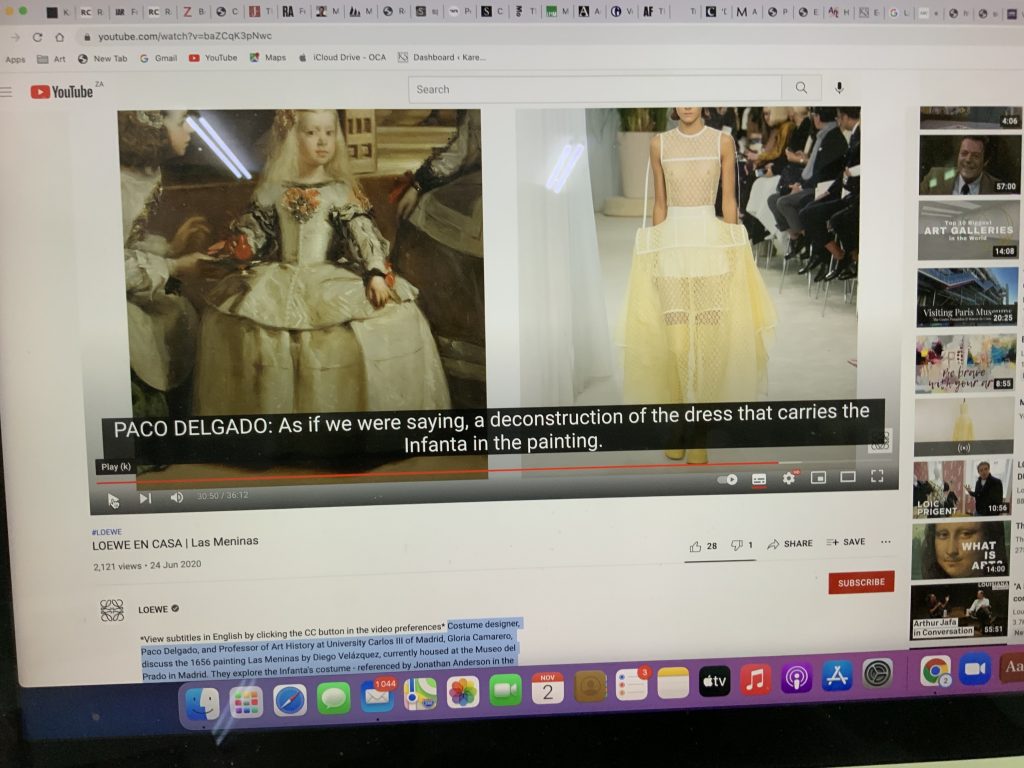

In the video below it became clear we will not be able to wear this type of dress today as women, we value how we move in our clothes. Here Paco Delgado refers to a translation towards modernity and our concern with comfort and freedom as women – about owning our bodies.

Clothing shapes a woman’s identity. In the Costume designer, Paco Delgado, and Professor of Art History at University Carlos III of Madrid, Gloria Camarero, discuss the 1656 painting Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez, as housed at the Museo del Prado in Madrid. They later in the video explore the Infanta’s costume – referenced by Jonathan Anderson in the LOEWE Spring Summer 2020 collection. With Anderson’s dress, the fabric is light, the boning structure is shown on the outside – I agree, he has deconstructed the dress! This modern re creation of the dress of the Infanta became a translation of the interior to the exterior. Delgado refers to the words: “who does not copy, does not create” (appropriating Picasso) when we look at this dress as a looking to the pass and interpret the work – its about knowledge and valueing the past when referencing the past.

I consider sculptures and drawing/painting. I want to focus on a series that brings about a different way of viewing a painting. The photographic work of Joel Peter Witkin really takes me to consider how I want to show and choreograph my narrative. I learn that In the place of the future Holy Roman Empress, Witkin photographed a double amputee. By recasting figures from celebrated historic works with contemporary individuals who represent a broad spectrum of humanity, Witkin exalts those individuals. His photographs are nearly always developed from a preparatory drawing and follow the same production process: firstly, he looks to create the mise-en-scène and distribute various elements that form its composition. Once the photograph has been taken, the negative pass through a process that includes the partial alteration of the photographic plate via the scraping of the emulsion, which alters what has been photographed. It is then completed with a selenium-toned or sepia-toned print.

In my sculpture below I challenged color and materials I could use to create a 3d image translating to the Infanta or the painting of Las Meninas. This 3-dimensional shape shows the form from all sides and looks at how color could be used in 3d shapes to make the form more realistic.

.

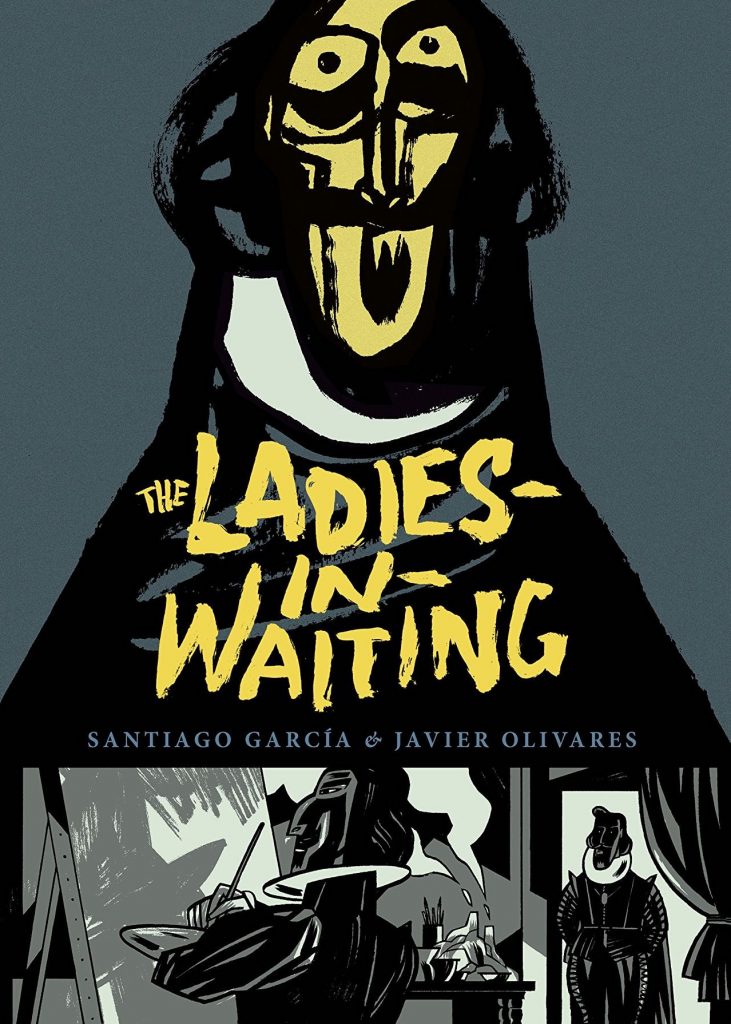

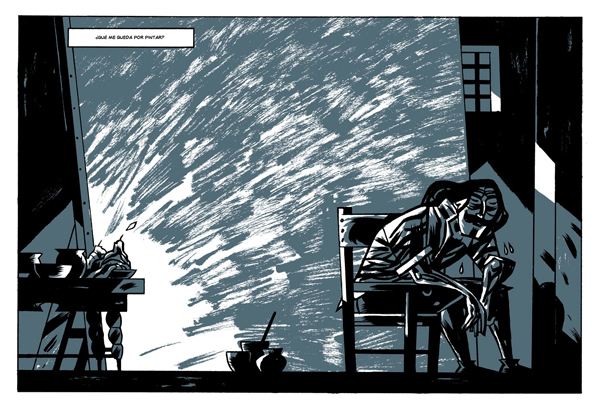

I found other reactions to the Las Meninas like that of Santiago Garcia and Javier Olivare. (http://www.abc.es/videos-otros/20140926/javier-olivares-dibujar-meninas-3807725194001.html)

Santiago Garcia and Javier Olivares’s ‘The Ladies-In-Waiting’ in this work they try to lift the veil of mystery over Velázquez’s famous work ‘Las Meninas’.

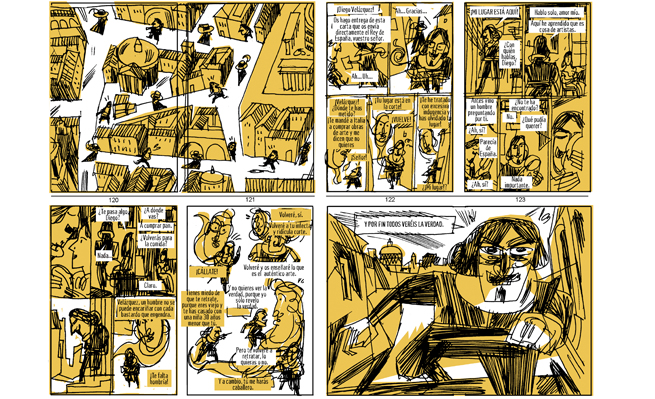

Las meninas (2014), Santiago García and Javier Olivares—writer and artist, respectively—tell, in words and images, the story of an enigmatic painting and painter. Moreover, García and Olivares build a paper museum inspired by Baroque logic: the painting within a painting; the exhibition of objects that question appearance; the promotion of an epistemological reflection of reality; and the presentation of a space of dialogue with a wide network of connections: combinations of shapes, colors, lights, and shadows. The graphic novel—a genre that became popular at the end of the 20th century—blends perfectly with the Baroque period, characterized by syncretism (the convergence of different genres), eclecticism (multiple theories, styles, or ideas), and decorazione assoluta.

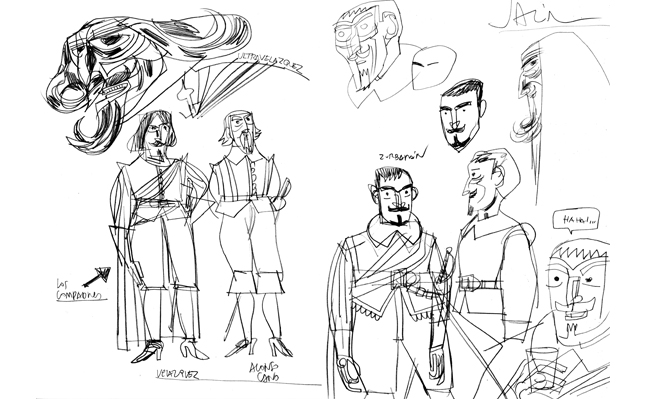

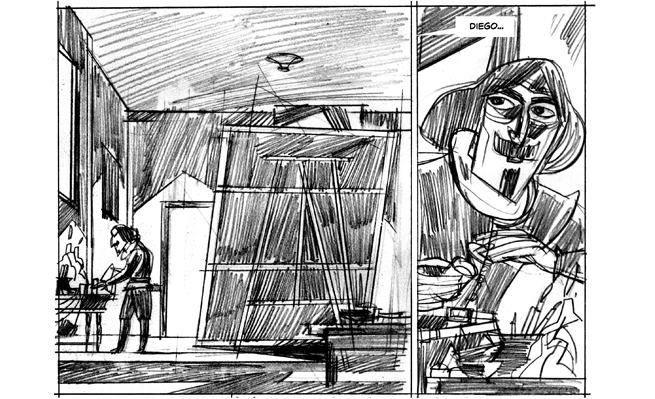

It is also a fictional account of a mysterious and famous painting and a fragmented history of its birth add up to make for an unusual subject for a graphic novel. Santiago Garcia and Javier Olivares’s The Ladies-In-Waiting is an attempt to unveil the mystery shrouding Spanish painter Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez’s famous work Las Meninas, while meditating about the Spaniard’s life. A postmodern novel with a touch of pastiche, an absence of verifiable facts, and accounts of events by unreliable witnesses, this graphic narrative is a smörgåsbord of ideas with broad flatline German Expressionist style illustrations. I found a website where I learned about an exhibition around the paintings of the book. This gallery had an exhibition, called, Drawing Las Meninas, 26 September 2014 – 16 November 2014. Here the gallery, ABC explains that “…This is not the story of an artwork, is the story of how an artwork becomes a status symbol and a new attempt to answer the question that generations of artists, historians, critics and comic book writers have done to themselves: What is the hidden secret behind Las Meninas?” The exhibition was divided into three narrative sections that explain the creation process of this graphic novel. It started with “The key” which shows part of the documentary material, original script pages, the complete storyboard and many early sketches. Then, “The Mirror” shows the process from pencil to inking to colored printed pages. Finally, “The Cross” holds the definitive pages in color, the original photomechanical plates and the cover design. In addition, original artwork made specifically for this exhibition is exhibited next to additional material not used in the book. As an epilogue, there is a study of the historical figures of Las Meninas, from Velázquez to Buero Vallejo or Equipo Crónica.

I read that the working process of this comic has been intermittent, and lasted six years. The first phase was documentation, and then, the scriptwriter did research around the graphic artist’s world. When writing a comic script is important to base your work on the illustrator’s imagination, style, and personality. It was important that the artist, in the way he sees, tells the story the writer imagines. (Each artist has a different way to see the world, and if the writer tells a story that does not adjust to the way they see it, this will end in a terrible result. Throughout the preparation process, the illustrator shares his sketches and character designs to help the writer see the story through his eyes. )In that sense, we can say the script is written with the drawings in the same way that is drawn with the words.

https://www.abc.es/cultura/20140926/abci-meninas-comic-museo-201409252022.html#

“They were appreciated not only for their unusual shapes and American origin, but also for the distinctive aroma and taste of the clay from which they were made. Búcaros were used to contain water and gave it a pleasing flavor. The clay was thought to have medicinal qualities, and it was fashionable among Spanish and Italian elites, especially women, to consume fragments of the pottery. This unusual practice made their complexions pale, which was considered desirable at the time. The popularity of this kind of pottery in Europe is well documented in the art and literature of the period. In Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, the infanta Margarita is served a small búcaro of water on a silver tray, while artists like Juan van der Hamen often included búcaros in their still life paintings. The Spanish dramatist, Lope de Vega, wrote satirically about the obsessive eating of pottery and its effects: “Girl of broken color, either you have lovers, or you eat clay.” (Niña de color quebrado / O tienes amores o comes barro.) Lope de Vega, El Acero de Madrid (1608)

More Las Menina interpretations:

.

Van Toth seems to be an emerging artist, and I found his work on an online gallery’s Emerging Artist Platform (Hansford and Sons Fine Art) It seems he is portraying the little infanta as levitating.

In 2018 the Spanish sculptor, Antonio Azzato created 80 fiberglass Meninas, designed by artists, musicians, and fashion designers and they were placed around Madrid.

The dress becomes a prison!

In 2004, the video artist Eve Sussman filmed 89 Seconds at Alcázar, a high-definition video tableau inspired by Las Meninas. The work is a recreation of the moments leading up to and directly following the approximately 89 seconds when the royal family and their courtiers would have come together in the exact configuration of Velázquez’s painting. Sussman had assembled a team of 35, including an architect, a set designer, a choreographer, a costume designer, actors, and a film crew

I would like to remind that de Beauvoir writes that women are trapped within their fashion choices due to their participation in dress codes/rules established by patriarchy throughout history, when I read the following:The purpose of the fashions to which [a woman] is enslaved is not to reveal her as an independent individual, but rather to offer her as prey to male desires; thus society is not seeking to further her projects but to thwart them. The skirt is less convenient than trousers, high heeled shoes impede walking; the least practical of gowns and dress shoes, the most fragile of hats and stockings are the most elegant; the costume may disguise the body, deform it, or follow its curves; in any case it puts it on display. Costumes and styles are often devoted to cutting off the feminine body from any activity… Paralyzed by inconvenient clothing and by the rules of propriety – then woman’s body seems to man to be his property, his thing… The function of ornamental attire is the metamorphize woman into idol

(de Beauvoir, p 543)

REFLECTION

Looking at how I worked, I feel it is good to start a quote from Alice in Wonderland. I am reminded of the White Rabbit asking the king where he should begin to read a set of verses (King reflecting in court): “Begin at the beginning” the Kind said gravely, “and go on till you come to the end: then stop.” As the King of Hearts said, stories should proceed from the beginning directly to the end – sequential. I developed images as I worked through research around the Infanta, which mainly concerned her role, her age, her gender, her dress, and her environment, or is it about place? The exercise suggested ‘before and after.

It seems that my process of making took the form of a narrative inquiry, as I gathered, analyzed,

and represented people’s stories I found on the internet and mixed them with my own. I believe in this way I challenge traditional and modernist views of truth, reality, and knowledge around the Las Meninas work. I believe it was my way of making sense and creating another layer of meaning to the work. I tried to work within the already known cultural context of the work, but considered how it would be to be the Infanta – some embodiment, or just fiction? Using camera technology of layering I could imbed time in a way: I made a drawing of the infanta and layered an image of my younger self onto that. It says something of my childhood and being a young girl in the 1960s, but also of the young Infanta in 1655. Did I temporalize space?

I realize that I was looking for self-expression and creativity in the process, as I prefer to think about clothing, but the body will always be encoded in culture. However, I feel these structured garments can be viewed as a cage. – a most flagrant way to expect women to be dressed in, where objectification does play an important role.

I do not think that in the end, I produced a series – this is much more a reaction in images upon imagines events, interrupted by time and place.

Bibliography

July 12, 1651: Birth of Infanta Margaret Theresa of Spain. Part I.

Elkins James, Time and Narrative, chapter 5, p 38 -49 online on

Engel, Charlotte, “Jumping through Hoops: The Rise and Demise of the Hoop Petticoat in the Eighteenth Century” (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1412.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1412

Kérchy, Anna. “THE WOMAN 69 TIMES: CINDY SHERMAN’S ‘UNTITLED FILM STILLS.’” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies (HJEAS), vol. 9, no. 1, Centre for Arts, Humanities and Sciences (CAHS), acting on behalf of the University of Debrecen CAHS, 2003, pp. 181–89, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41274221.

Smith, Bernard Museo del Prado – Velázquez and ‘Las Meninas’ 20 November 2019

Wunder, Amanda. “Women’s Fashions and Politics in Seventeenth-Century Spain: The Rise and Fall of the <em>Guardainfante</Em>.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 1, [The University of Chicago Press, Renaissance Society of America], 2015, pp. 133–86, https://doi.org/10.1086/681310.