TOPIC 2: INSTITUTIONAL CRITIQUE

EXERCISE 4.2 TRANSPARENCY

Research the types of galleries and cultural institutions where you live. What are you able to find out about them? Record your findings in your sketchbook in a form you find appropriate. Are they privately or publicly funded; who runs them; who sits on the board; who works for them and on what kind of contracts; what roles do they have – curator, janitor, cleaner, technician; what is the gender, ethnicity, class, age of these people?

[I decided not to venture towards the questions above. I believe it will be in-appropriate to address it on social media (my website/blog) for reasons of strict local laws on privacy and personal opinions on social media in the UAE. I tried to contact a private gallery, but had no success. ]

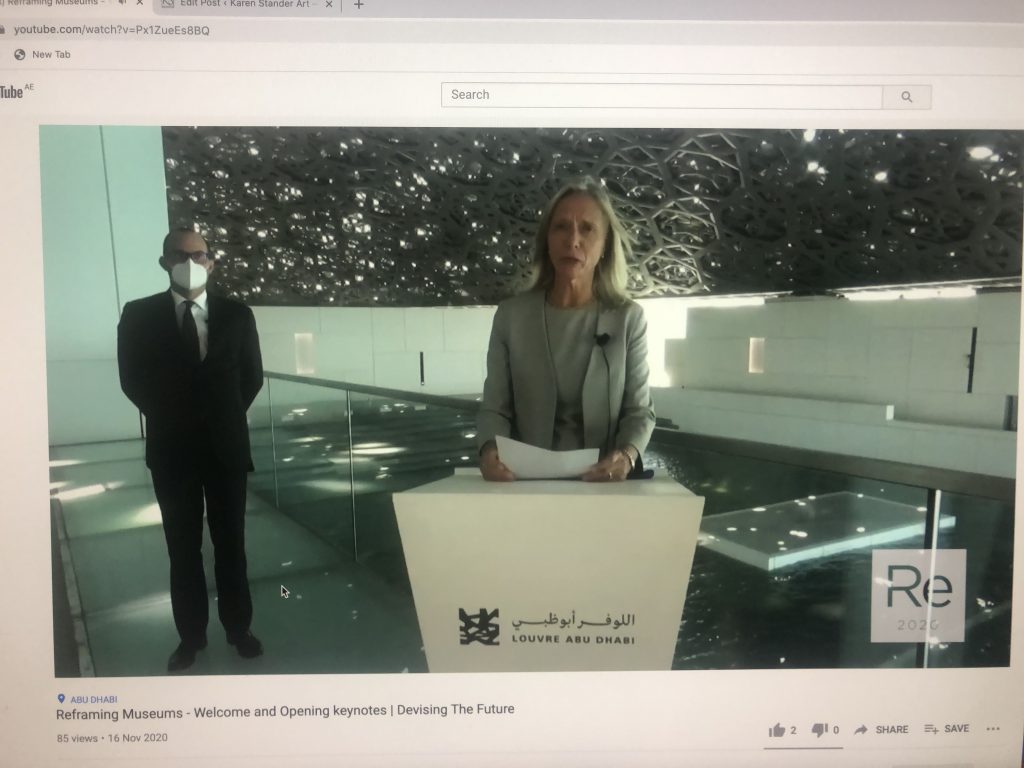

Instead: I looked at a Symposium the Louvre Abu Dhabi initiated and which started today, 16 November 2020 and will continue for 3 consecutive days. The talks is called Reframing Museums 2020 and is in the form of a webinar – also streaming on Youtube due to high demand for attending. It was opened by short keynote talks by the Chairman of the Dept of Culture and Tourism, and the Vice Chancellor or the NYU in AbuDhabi as well as the Director of the Louvre Abu Dhabi. A main message is that of the inequities that the global Covid pandemic laid bare across the world and the importance of culture as a backbone of society and that museums can act as connecting points. There was reference made of how understanding and learning from each other’s culture and religion brings forward acceptance, which is part of our humanity. Here a reference was made of universality and I found it a good metaphor as it seem it is accepted that all humans are concerned with acceptance, within the bigger ideas of being different. The museum becomes a connecting space ( a physical site, but in many places around the world, for many different people) – this can happen through learning about other cultures and having an experience with these objects and making your own interpretations about this ‘universal need’.

In the introduction pamphlet it was stated that the organisers plan to talk about what museum model is needed for the future? Whom are museums for? With notions of ownership and expertise being questioned, how can museums contribute meaningfully to our rapidly changing world? Over the 3 days they will discuss 3 major pillars that they consider have traditionally supported museums , namely collections, buildings and site and people.

I made some notes of the vice chancellor’s opening remarks (seen below in a screenshot) when she referred to museums as sites that want to present collections that are preserved, interpreted and shared – it is about what and who museums are for. How they decide to be a site that can be visited physically or virtually. That this site is today a place that bring people together, as well as a space where all people should have a say to what a museum brings to them. She states; “a difference from the past when it was seen as treasure houses for persons with certain expertees or level of education“. My understanding after listening is that Louvre Abu Dhabi aspires ideas of being a universal museum – is has a commitment to the universality of knowledge and understanding that universal experience is one of difference.

Feedback and reflection on Roundtable 2 discussions on 17 November 2020

The first speaker was from Shanghai Museum – This museum was closed for 49 days during Jan-March 2002 due to the pandemic and after opening with a daily limit of 2 000 visitors it is currently operating on 75% of total visitors compare to before the pandemic outbreak. Booking online, social distancing is required and the responsive actions brought in to operate under the treats of the pandemic. During the pandemic they launched an online program for virtual visits, extended current exhibitions, but suffered by having to postpone planned future exhibitions and and end to exchanges with international museums of art works. They focus on seeing art as ‘a power’ to unite – one realise how institutions can say this within the difference of political scenarios. A question is opened: are we in the post pandemic world, or are we in a current world, an neo pandemic world? The panel member from Spain, the director of Reina Sofia, Manuel Borja-Villel highlights the ecosystem in which a museum operates as a public service, which includes artists, mediators, producers – he refers to the catastrophes brought along by the Pandemic, not a pandemic with crises, as he says, capitalists systems are used to crises, but not to catastrophes such as this – it paralysed everything, the museum understand its role to support this ecosystem. Their visitors are currently only people from within Madrid, and they need to plan for this, and see the need these visitors display to visit the museum – the locals show how they embrace these visits to these places. He refers to a dilemma of Collections versus temporary exhibitions – both have a role and should not be privileged above each other Temporary exhibitions plays an important role, they pushed forward future exhibitions – locals can still visit. I valued critical thoughts they are considering to ideas, like he said the “spectacularization of art” – turning creativity of art into an industry. Trying to keep this moment to rethink what the museum of the present (future) – he does not think museums should contra-pose collections to exhibitions – think long term exhibitions – changing the idea of visiting collections to looking at living exhibitions other timing. Museums should speak from one place – not local, nationalistic, physical bounded – should be solidarious – share collections. He refers to Darrida – says museums should be hospitable – he refers to language and rules – a place for refuge and place for creativity.

EXERCISE 4.3: CONSTRUCTIONS OF KNOWLEDGE

In the study notes: Images of artworks to include within these course materials have been sourced from Bridgeman Education. It has been difficult to find the work by many important women/ethnically diverse artists. The organisation is a subscription service to educational establishments. Knowledge on Wikipedia, on the other hand, is created by the public for free universal access. Do you use Wikipedia? Currently, the majority of the contributors and editors that determine its content are white men based in Europe or North America. This particular demographic determines what is included and the interpretation of knowledge. Use Wikipedia to search for artists where you live. What observations can you make? Record your observations in your learning log.

I consider constructions of knowledge in terms of my art education in the rest of this paragraph, and of how I find meaning through research on topics/exercises and practical making through books, videos, video tutorals, online library and online sites. I would like to think the idea of my own interaction with these mentioned tools is better than a hierarchical system I was brought up in, where school and university had a syllabus and certain books and lectures with certain viewpoints and expected outcomes, very much in line with the political institutions of the day – most prescribed books were written by local academics. By my final year (Honn) I was using American books, but only selected few scholarly articles. Wikipedia and the internet is a new construct – physical visits to libraries and materials like encyclopedias were my supports, apart from handbooks and class notes made from attending lectures and practical sessions. I enrolled for post graduate learning later in my life (2006/7) and was ‘exposed’ to the internet as a search and reference site, but also had access to a student for assisting in library searches, as well as more open discussions with lecturers and fellow students in open debate in classes. I do think it is important to consider how I define this knowledge: I believe it is built on the foundations of scientific facts/’truths’, based on truths, which is facts (and theory) – like climate change and gravity: those are not opinions (mixed with values and identity where politics and other cultural ideas plays into as we are currently seeing playing out in the USA elections) Having said this, I am fully aware of biases and interpretation of facts in how we ‘curate’ our own sense of reality. Social media platforms is used by people with power in politics and economy to use ideas that ‘fake’ news and conspiracy theories to play into our values and identities when things become inconvenient. It is very much about our WHY’s – why to I prefer to believe and or disbelieve XYorZ, not why do I disagree? Schools play an important role in opening up these critical skills of being open ( discussion and listening) to our biases and beliefs. I do belief art has a role to play in culture – not to fight against those who disagree, but to understand WHY they disagree.

This takes me to my own practice and ideas for my parallel project – I should not downtalk to anybody, or judge them, I should pull them into the discussion and connect them. My rhino drawings should not be seen as judgemental or blaming the other – it should invite discussions for solutions and empathy.

It was interesting to read on the Wikipedia Website that they refer to the site as an ‘online encyclopedia”. I have viewed Encyclopedias a something being ‘outdated’ to quickly, thus my lack of trust in them – lovely for images when you had to have visuals of things and places ( all truths and facts) you have not been exposed to. I believe in most households of the early 50’s/60’s good intentioned parents bought it as an investment into their children’s education. Now it gathers dust on a bookshelf or is kept as a memory.

In the Independent (online version) I read the following: ” A spokesperson for the Wikimedia Foundation said: “Wikipedia has been edited by millions of people around the world who have contributed more than 35 million articles across 291 languages. These volunteers make up a vast, diverse community that can’t be defined by any single set of characteristics. No single group controls Wikipedia — editors come from a variety of backgrounds, and each person has unique reasons for editing” I am a bit of a sceptic on the sources as well as ‘researches’ for content on the Wikipedia site – I see the bigger picture of open access to information, but am also aware of measures of control driven by bias and power, be it gender, political or economical. A outgoing founder member criticised the leadership for being anti elitist and went on to establish Citizendium, a rival “free knowledge project” where user generated content would have to be approved by editors with minimum levels of qualifications, such as college diplomas or degrees. I have had very good experiences by using artist own websites and that of galleries like Tate, MOma and the National Gallery when information is needed. I feel it can be trusted as it is written by art scholars with good academic background as well as it being a very reliable source or research. The following statement is found on the Wikipedia website:

The reliability of Wikipedia concerns the validity, verifiability, and veracity of Wikipedia and its user-generated editing model, particularly its English-language edition. It is written and edited by volunteer editors who generate online content with the editorial oversight of other volunteer editors via community-generated policies and guidelines. Wikipedia carries the general disclaimer that it can be “edited by anyone at any time” and maintains an inclusion threshold of “verifiability, not truth.” This editing model is highly concentrated with 77% of all articles being written by 1% of its editors, a majority of whom are anonymous.[1][2] The reliability of the project has been tested statistically, through comparative review, analysis of the historical patterns, and strengths and weaknesses inherent in its editing process.[3] The online encyclopedia has been criticized for its factual reliability, principally regarding its content, presentation, and editorial processes. Studies and surveys attempting to gauge the reliability of Wikipedia have been mixed, with findings varied and inconsistent.

Select assessments of its reliability have examined how quickly vandalism – content perceived by editors to constitute false or misleading information – is removed. Two years after the project was started, in 2003, an IBM study found that “vandalism is usually repaired extremely quickly—so quickly that most users will never see its effects”.[6][7] The inclusion of false or fabricated content has, at times, lasted for years on Wikipedia due to its volunteer editorship.[8][9] Its editing model facilitates multiple systemic biases: namely, selection bias, inclusion bias, participation bias, and group-think bias. The majority of the encyclopedia is written by male editors, leading to a gender bias in coverage and the make up of the editing community has prompted concerns about racial bias, spin bias, corporate bias, and national bias, among others.[10][11][12] An ideological bias on Wikipedia has been also identified on both conscious and subconscious levels. A series of studies from Harvard Business School in 2012 and 2014 found Wikipedia “significantly more biased” than Encyclopædia Britannica but attributed the finding more to the length of the online encyclopedia as opposed to slanted editing.[13][14] “

I found a reference by them to an article in the Guardian> Firstly here is their comments:

On October 24, 2005, British newspaper The Guardian published a story titled “Can you trust Wikipedia?” in which a panel of experts were asked to review seven entries related to their fields, giving each article reviewed a number designation from 0 to 10,[41] but most received marks between 5 and 8.

Wikipedea share their feedback: “The most common criticisms were poor prose and ease-of-reading issues, inaccuracies with omissions and poor balance. The most common praised were :Factually sound and correct, no glaring inaccuracies Much useful information, including well selected links, making it possible to “access much information quickly” (3 mentions)”

I then read the article and it is clear, this is an open source of information,with no knowledge about the ‘researcher’ or person who place the data, but self regulated by its users. It is up to me to trust them, verify their information and make my own decisions on its validity. The author,David Barnett, comments as follow:“..….But Can We Trust Wikipedia?”. And the answer is, we can trust Wikipedia just about as much as we can trust anyone who tells us anything. But Wikipedia, perhaps contrary to popular belief, isn’t a source of information at all. Lubbock says, “Wikipedia entries are basically built upon the architecture of knowledge that we already have.” (Independant, 17 February 2018) So they are building upon knowledge in published books and other articles that exists – one can check these references, up to you to take this responsibility. I do not think knowledge about art, the artworld and artists would be sufficient if I rely on what other people tell me – I still need to verify and do my own critical review where I can reference and verify information.

I will thus give it a try by researching two local female artists (middle Eastern region) one is an Emerati artist, Maisoon Al Saleh and the other a Beirut based artist, Tagreed Darghouth, whose work I have got to learn about during an exhibitions in Dubai, and since then followed them on social media. I have hardly used Wikipedia to search for my studies. I do have the WikiArt App, a great reference for images.

On Maisoon Al Saleh I found the information outdated and not in touch with her latest shows and profile. (can this validate my critic that encyclopedias can be right, but outdated with information?) They state her artistic style is Surrealism – she is known as a Multi disciplinary artist and have been growing her audience as far as Europe, Northern Africa, Asia and the USA. Again not up to date. I visited her website – which I would definitely use if I had do research her work. It is full of images of her work, gives information I would find useful to learn about her work practice and own artistic development.

On Tagreed Darghouth, the Lebanese born artist, I do not find much information, and the site was last updated in 2016. Below are some of her works on view in Dubai over the last two years. She is currently exhibiting in Dubai – I plan to visit the exhibition later this week. I found much more information on other galleries who exhibit her work. I feel Wikipedia is outdated and selective with information. I

EXERCISE 4.4: INSIDE/OUTSIDE THE INSTITUTION

In this topic, you have examined challenges made from inside and outside the institution such as Occupy Museums.

Many artists attempt to challenge the status quo from outside the institution. In 2009 James Brett founded the Museum of Everything in North London showing ‘outsider art’ or ‘nonacademic art’. The exhibition was so popular that it drew enormous queues on the streets and has since toured the world. Initially a non-profit museum, it currently manifests in Marylebone as a commercial gallery. Occupy Museums was created in the first month of Occupy Wall Street in New York in 2011 to highlight economic inequality within cultural institutions. It stages campaigns and actions at galleries and art fairs. The Exhibitionist organise uncomfortable art tours in major U.K. institutions as an alternative to the tours that might be provided by them. However, unlike Fred Wilson’s Mining the Museum, these are not interventions that are sanctioned by the institutions. The tours have attracted significant attention and museums are increasingly trying to avoid embarrassment by including them in their programmes.

I looked at a video in which James Brett talks to an audience about the ‘Museum of Everything” and PINC.15 He calls himself an accidental museum founder. He shares his thoughts about art and outsider art, and suggests that art is a ‘bit of a construct’, he feels something was lost in the ‘neutral environment’ of the the gallery. He looks back at cave art – says people have always been looking at it, liking and admiring it over history. He looks at why we create and what we create and what we expect when we go to look at art. I like when he asks – is the cave a studio, is it a gallery? When art was defined, there was a big seperation, split between high and low art. Words related to the work considered as low art: brut, folk, naive, primitive, outsider – he refers to artists with mental illness, secret working as artists, or self taught, or not known, learning disabled, black and female artists – dismissed by mainstream society, not considered artists because they have not been trained. He focussed on creating empathy with the viewer and work in his exhibitions. One look at the works and become aware of artists who are not seeking ‘praise’, whose journey is the “destination”. Brett refers to it as “a form of energy, a manifestation of innate behaviour or a byproduct of an urgent monologue” .

In 1997 Julian Stellabrass wrote an essay Money, Disembodied Art, and the Turing Test for Aesthetics here he surveys contemporary art and suggests that art is ‘currently’ in a great deal of trouble: with a feeling that

art is currently in a great deal of trouble: “…high culture appears to have pulled up at a dead end, though somehow artists still carry on making things […] culture is stripped of the narrative of modernism, of the promise of a happy ending, and when even the liberatory promise of postmodernism has declined into market-niche relativism, it is hard to know how, where or indeed why to proceed. (Stallabrass, 1997, p. 70)

The exercise asks the following: Can you find examples of artists making interventions where you live, or close to where you live? In your learning log record your observations regarding the types of challenges being made. Compare the objectives and achievements of those made within the institution and those made from outside it.

Below is work of the Palestinian born artist, Hazem Harb. HIs work is regularly displayed by a local gallery, and he had held open days at his home studio here in Dubai. (I wrote more about him in my Parallel blog for Part 4) As an artist he found a way to make art about being out the outside and addressing a Palestinian imaginary. “You miss your place, your country,” he says. “You are not allowed to be there. It becomes a phantasm. It was so hard for me to see Palestine from outside, not from inside. When you are inside the situation, you do not see it. But when you are outside, you see it from a grand angle.” I place his work in this context as I look at global politics around the Arab world where I currently life. President Trump’s travel ban has closed the door to people from some Arab countries like Syria and Yemen and some of the prominent American art institutions such as the Met and MoMA have reacted, by taking an opposite approach, concentrating on Arab and Palestinian art in their exhibition programs. “The international as well as the Danish art scene are currently experiencing an increased attentiveness to the work of Arab and Palestinian artists. For instance Danish-Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour has been selected to represent Denmark at the Venice Biennale this year” says Masha Faurschou. (placed by a Copenhagen gallery, Sabsay, where Harb had an exhibition during Feb/March 2019)

I reflect on contemporary art and the institutions – which I agree with Brett, is very much about the object and money – we tend to forget the role of creativity and that there are other ways to think about art. The art he shows brings the awareness that much of art goes ‘undocumented’ due to the idea of how museums functions as space for art viewing. Is it then as some consider, a continuation of Art Brut?

In 2005 Fraser wrote that the institutional critique has been institutionalised by the museums. One increasingly finds institutional critique accorded the unquestioning respect often granted artistic phenomena that have achieved a certain historical status. That recognition, however, quickly becomes an occasion to dismiss the critical claims associated with it, as resentment of its perceived exclusivity and high-handedness rushes to the surface. Fraser asserts institutional critique has become an accepted part of the art historical narrative, and is now invited into the institution, and through that has lost it’s vitality. She cites the Los Angeles County Museum’s conference entitled, “Institutional Critique and

After”, Daniel Buren’s major installation at the Guggenheim in 2005, a replica of his work of institutional critique that was removed from a show at the Guggenheim in 1971. She said that discussions of institutional critique have become “nostalgic” for an “era before the corporate mega-museum and the 24/7 global art market, a time when artists could conceivably take a position against or outside the museum.” She argues that this change isn’t something that just happened, but that in fact artists who worked with strategies of institutional critique within the museum, were always part of the institution. Even Haacke, in “The ‘Art’ Thats Fit to Show” written in 1974 admitted that artists are not outsiders to the institution.

“Artists” as much as their supporters and their enemies, no matter of

what ideological coloration, are unwitting partners in the art-syndrome

and relate to each other dialectically. They participate jointly in the

maintenance and/or development of the ideological make-up of their

society. They work within that frame, set the frame and are being

framed. (Haacke, 2006, p. 55) So these artists as critiques from the outside say that artists are part of the institution, and that critique of the art institution is self-critique. As the study notes confirmed they agree that many of the artists who practiced institutional critique were seen as outsiders, but in fact they were working within the institution.

More research

I have by now realized that in my Parallel project I look to qualitative research methods – subject to self analysis and the development of ideas and concepts – and hopefully some explanations. I am very aware that in this effort I need to acknowledge the bigger picture It became clear that politics and economics have been drivers of power in art over most of the history of art. Modernism is closely linked to socio-political and ideological phenomena. I realise that I am looking into something which is much bigger than what I will even be able to discuss, but after reading about the work of Haacke and Kurt Schwitters and how MOMA travelled the world to find modern art as well as about the Dada and Surrealist artists, I wanted to understand how Hitler influenced art in Germany and the effect it had on the rest of the world. (a few years ago there was a Hollywood movie about this period) I read that he had been an artist before he was a politician and that his ideas of aesthetics to be used as propaganda for his political agenda. Interesting was to learn that he was twice rejected for a place at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts. He arranged the Entartete Kunst exhibitions in 1937 (or ‘Degenerate Art’) and it was a derogatory term adopted by the Nazi regime in Germany by displaying works deemed to be ‘an insult to German feeling’. It went on to tour the country. The idea was not just to mock modern art, but to encourage the viewers to see it as a symptom of an evil plot against the German people. Some of the art was later burned by the Nazis. The art was also exhibited in a way to mock it – texts/ slogans on the walls indicated to madness in the methods. The sad part of this whole effort was the fact that the German people had no freedom to judge or critique the art or the exhibition – due to censorship and propaganda of the political power.

The ‘degenerate’ applied to almost all German modernist art, and works by international artists such as Picasso were seized. On Moma and BBC websites I learnt that these works became more attractive abroad, gained value because the Nazis opposed it. It was suggested that over the longer run it was good for modern art to be viewed as something that the Nazis detested and hated. Some of the artists featured in the exhibition are now considered among the greats of modern art – Paul Klee, Oskar Kokoschka and Wassily Kandinsky, Otto Dix, Ernst L Kirchner – along with famous German artists of the time such Max Beckmann, Emil Nolde and Grosz.

I want to consider the reaction of artist on political and cultural repression in regimes all over the world when one look at the role of museums and galleries within institutional critique. We will always need to excavate the past, and seek to understand the psychology, ideology and political culture from that perspective. I feel this has something to do with how viewers should be informed about more than just the provenance of a work of art. Some things should not be allowed to forgotten by society – we need to have history in order to understand life.

[Institutional critique] has aimed to clarify the legitimate bounds of critique, but in this case, the bounds have been drawn around the type of critique artists could, in good faith, level at the institution of art, while also embodying it professionally, socially, psychically, and economically. This soldered artists and institutions together in an increasingly half-hearted tableau vivant of autonomy, a reconciled realpolitik not all that different from the kind that anointed liberal democracy as the least-worst form of government still standing after everything else has ostensibly been tried.

—Marina Vishmidt, 2017

I ask myself how opaque are the politics of art? How many artists obscure there opposed values?

Can art become more self-conscious?

Is art is the critical alternative to society?

Should I consider to look into my own artistic ambition?

Critique, or the detailed and systematic study and analysis of systems and concepts, has always been part of artistic production (to greater or lesser extents depending on individual contexts and examples). In an artistic context, to say that an artist is engaging in a critique of something often suggests a negative slant to their analysis, or an attempt to reveal ethical or systematic problems about that which they are assessing.

Reading on the website of Artstory and how they describe Institutiona Critique is agree that when an artist engage in Insitutional Critique, it is usually understood to be one that reflects the negative aspects of artistic institutions as they see it, which might include galleries, museums or the art market. It talks about the ‘unsayable, the controversial -what cannot be said or displayed, and why not? One needs to ask what lies below this need to reveal the political, financial or social underpinnings of the art world? Surely it moves into directions such as activist artistic projects, often including work that addresses access and ethics in relation to issues of gender, race, class and disability – and then it should be true that when any artist confronts the deficiencies of the gallery through their work might then be said to be engaging in a kind of Institutional Critique. How are these borders described today – what is ‘inside’?

In the E-flux magazine (2020) I read the following: ” Marina Vishmidt describes the symbiosis between many critical artistic gestures and the institutions that exhibit and historicise them by comparing institutional critique to the illusions of neoliberal democracy. For decades, artists and arts writers have negotiated this mutually beneficial interaction with a theorisation of “inside” or “outside” positions with respect to sites of exhibition, display, and presentation. This speculation on the spatial, linguistic, and most importantly political borders of the institution is embedded in many questions that cultural workers have been asking themselves since at least the 1970s: How complicit am I? Can I still critique while inside? How to subvert while maintaining my autonomy? How much autonomy should I relinquish? What is the border between the museum and the statist, racialized, capitalist, neocolonial, gendered violence that produces its material wealth? ” She also states: “It’s only more recently that grassroots groups (some including artists) have reframed the last question by acknowledging the border as nonexistent, while incorporating into their tactics the belief in that border exhibited by systems of power“

I wonder, should one look to the artists that we never allowed ‘into’ the institutions? B Looking at artist, D’Arcangelo, (1978) who after his radical actions has been banned from most museums/institutions, one could argue that institutions are fine when art critiques its methods of value production from the inside, but not when that value is targeted or put at risk. It is quite extreme to think that he removed a valued piece of art inside the Louvre, put it on the floor, put up his art (written manifesto), without being observed. I find the artist reactions, by printing his actions, which seemingly did not get the reaction he wanted, a bit disturbing – but then again one should view it in context of the time, when he focussed on the democratisation of how art were produced (role of the artist) and received (status of art) within institutions – social conditions of art .

Artstory: Institution Critique pdf online publication at https://www.theartstory.org/movement/institutional-critique/history-and-concepts/ Accessed on 27 December 2020

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-24819441

Burns, Lucy, 2013, Degenerarte Art: Why Hitler hated modernism, BBC World Service, accessed online on bbc.com on 20 December 2020.

Farago Jason, 2014 Degenerate Art: The attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, 1937 review – what HItler dismissed as ‘filth’ , The Guardian.com

Petrossiants, Andreas, 2020, Inside and Out: The Edges to Critique, E-Flux, Journal 110, accessed online on 3 January 2021)

Stellabras, Julian (1997). Money, Disembodied Art, and the Turing Test for Aesthetics. In thesis of Sophia Kosmaoglou, June 2012 THE SELF-CONSCIOUS ARTIST AND THE POLITICS OF ART: FROM INSTITUTIONAL CRITIQUE TO UNDERGROUND CINEMA read online at : https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/8000/96/ART_thesis_Kosmagoglou_2012.pdf , accessed on 3 January 2020.