RESEARCH POINT 1

Research some of the artists that subsequently emerge as a result of these shifts. Look up:

- Kurt Schwitters, Merzbau, 1937;

- Marcel Duchamp, 1200 Bags of Coal, 1938;

- Roy Lichtenstein, Stretcher Frame, 1968.

- Look at installation images of exhibitions by Frank Stella,

- Kenneth Noland and

- Helen Frankenthaler.

Kurt Schwitters

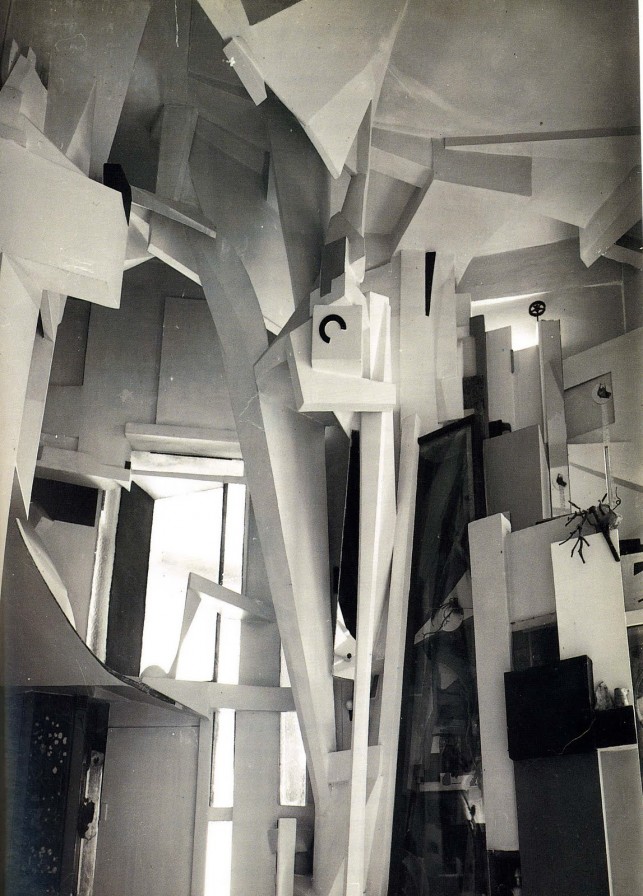

Below is a picture of Merzbau, left and a re creation right.

The artist worked on this piece during 1923 to 1937. He fled to Norway to escape the threat of Nazi Germany, and whilst in exile in 1943, the work was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid. The work was made inside his home and Barr saw it during a visit in 1935, unfortunately the artist was not home, but on holiday in Norway. I found this story behind the work fascinating and followed a trace that led me to interaction with A Barr, from MoMA. A letter in an article, which Barr’s wife wrote, ( Sudhalter, 2007) tells it better: “It is like a cave; the stalactites and stalagmites of wood junk and stray rubbish picked from the streets are joined together to fill the whole room from floor to ceiling and walls to walls. A.[lfred] and M.[argaret] are silenced. The effect is mesmerizing. How did the artist intend to display it? What I gather from this is, A Barr (and his wife) liked the work, saw its significance, but the size made it impossible for them to consider getting it to New York. In 1936 Barr included some of Schwitters work in a Moma exhibition, Cubism and Abstract Art and in Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism he showed two images of the Merzbau structures, in a section on Fantastic Architecture.

After these photos of his work were requested by Moma, Schwitters suggested in a letter to Barr that he can make a new Merzbau to be exhibited by MOMA. Here he was adamant that his work was cubist sculpture into which people could go and not architectural in terms of interior design or decorative style – he called it Raum Abstract Interior.

A copy of the letter reads : “In order to avoid mistakes, I must expressly tell you that my working method is not a question of interior design [Raumgestaltung], i.e. decorative style [dekorativer Art]; that I do by no means construct an interior for people to live in, for that can be better done by the new architects. I am building an abstract (cubist) sculpture [abstrakte(kubistische) Platik] into which people can go. […] I am offering now to design an abstract interior,..”(Sudhalter, 2007) Sudhatler claims that had the artist made a different appeal to Barr, Barr might have saved the Merzbau in Hamburg, as he also feared what the war could do to the work. During the war the artist was in a camp in England and the USA was not interested in granting him asylum and or to buy more of his works. It was only after Barr was removed from his position, after the war in 1946 that there was a more favourable view on his work again, when he found that he might be able to save some of the pieces left of his original work in his home in Hamburg. Sudhalter shows a letter which shows the artist’s intent:

“I shall raise money in America. I could sift through the fragments or remains the way ancient ruins are excavated, and sell them to Americans. I could live on the proceeds while this was going on.” By now MOMA was also interested in any photographic material, but the work seemed to be beyond repair.

The work was a room sized living sculpture according to notes I found on the MoMA website. On the MoMa website I read the following: “Schwitters’ art was more than just the collage object itself. It was a whole process, philosophy, and lifestyle, which he called merz—a nonsense word that became his kind of personal brand. He was a merz-artist who made merz-paintings and merz-drawings, and naturally, the place where he merzed—his studio and family home—was his merz-building, or Merzbau. Over the years, this Merzbau developed into a kind of abstract walk-in collage composed of grottoes and columns and found objects, ever-shifting and ever-expanding”. (Moma.org)

The Merzbau has become a kind of art-historical myth, and one that has influenced many artists since. The definition of art shifted in the 20th century, and many artists now create not only paintings and sculptures, but also installations, happenings, performances, and other works that can be hard to research.

Manzoor gave the following description: “The Merzbau involved two dimensions. The first dimension consisted of a crafted architectural structure made of plaster and wood, and built up along multiple, irregular axes. The second consisted of an inner core, a formless accretion of discarded random objects and fragments. The interior and the shell-like enclosure connected to one another through labyrinthine, miniature tunnels or voids, which doubled as spaces for the display of objects. Schwitters used these spaces to present other assemblages or collections of things taken out of everyday circulation.” (Mansoor, 2002) Merzbau was a continuous project altered daily, small apertures were often sliced out of a larger mass, or covered over and buried under the agglomeration of objects, wood or plaster. Mansoor also said that Richter “generously saw Merzbau as a living, daily changing document on Schwitters and his friends.”

Then I read this in the article by Mansoor:

In a short essay entitled “Balance Sheet—Program for Desiring-machines,” (1977), addended to the 1997 French edition of Anti-Oedipe,17 Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari refer to Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau,18 as “the desiring house, the house machine of Kurt Schwitters which sabotages and destroys itself, where its constructions and the beginning of its destruction are indistinguishable.”19 The word “house” introduces less a sense of architectural structure than of a site of specialized production, a process, indicated by its slippage into the word “machine.” For Deleuze and Guattari, the compositional, anti-structural set of relations, cuts and connections enacted by Merz, constitute it as a desiring-machine. For the field that links objects, materials, and processes is not the coordinates of a coherent structure, but rather the aleatory encounter between materials and processes. The (dis) connective tissue itself, as a set of ruptured and re-connected points of intersection constitute the machinic assemblage. This machine, in turn, produces and is produced by affiliations between scraps and residua, or chance relations between elements that are ultimately distinct. It is “the un-connective connection of autonomous structures…that make it possible to define desiring-machines as the presence of such chance relations within the machine itself.”20 In other words, the machine is the space of excessive process, the production of production producing normative, hegemonic forms of production differently. I set the “Balance Sheet Program for Desiring Machines” into play throughout the present essay for its singular capacity to describe the Merzbau’s operative mode. It presents a chance to rethink an artist’s project as performance and practice—a set of activities irreducible to any object status answerable to art historical evaluations, which are founded on the seeming stability of the object.

It reminds me of the works of the architect Gaudi I saw in Barcelona – like the Basilica Familia Sagrada that is still an ongoing project. Schwitters also continued, even after the first Merz was destroyed.

Moma website: https://www.moma.org/explore/inside_out/2012/07/09/in-search-of-lost-art-kurt-schwitterss-merzbau/ Accessed on 4 November 2020.

Mansoor, Jaleh, 2002, Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau: The Desiring House pdf read on https://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue4-IVC/Mansoor.html accessed on 4 November 2020.

Sudhalter, Adrian, 2007, Kurt Schwitters and The Museum of Modern Art in New York on Academia.edu https://www.academia.edu/39014836/Kurt_Schwitters_and_The_Museum_of_Modern_Art accessed online on 4 November 2020.

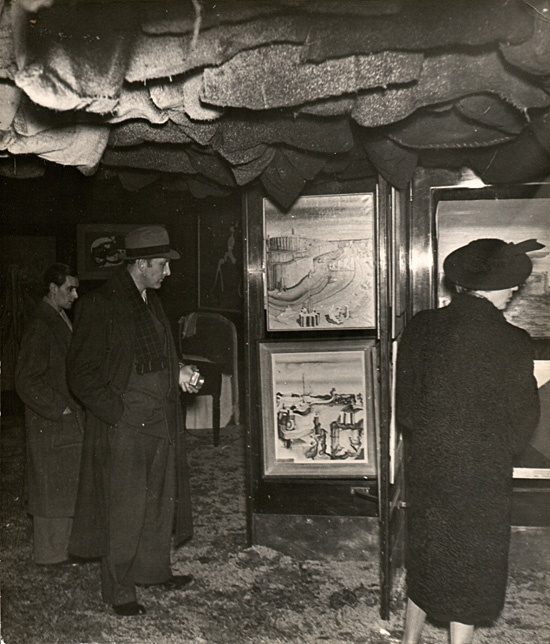

Marcel Duchamp, 1200 Bags of Coal, 1938.

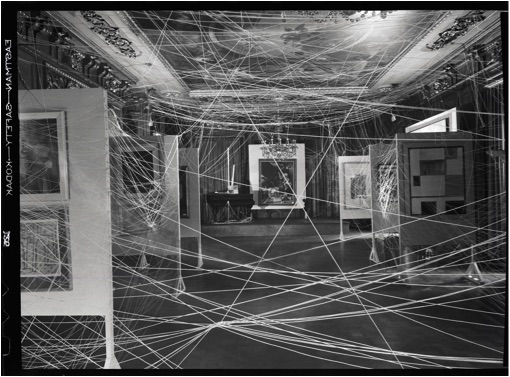

The exhibition took place in a prestigious venue, the Galerie Beaux-Arts. O’ Doherty wrote that Duchamp originally wanted to use umbrellas. Leading to above installation was a corridor of 16 female mannequins a reminding one a bit of fashion shop displays. Viewers were given flashlights/torches, its seems disorientation and uncomfortability was an important intention by the surrealist artists for a viewer experience. This exhibition ran from 17 January until 24 February was by Georges Wildenstein, at 140 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. It it was divided into three sections featuring paintings, objects, unusually decorated rooms, and redesigned mannequins.

Meecham claims that the idea was not to have a contemplative experience. The floor was covered with a layer of sand and dead leaves and above the visitor’s head dark bags were hanging close by. The inversion pointed to how the ceiling as space was not conceived as ‘a space for art’ in the white cube idea.(Meecham 2005: 471-473) It also seems that Meecham saw that through concealment Duchamp exposed the myth of art’s autonomy and showed art is complicit in the fiction of the gallery and its romance with the artist. O’Doherty concludes that Duchamp should make one think as to who he addressed this work: “Are they to be delivered to the spectator, to history, to art criticism, to other artists? To all, of course, but the address is blurred. If pressed to send the gestures somewhere, I’d send them to other artists” ( O’Doherty,1986 :71)

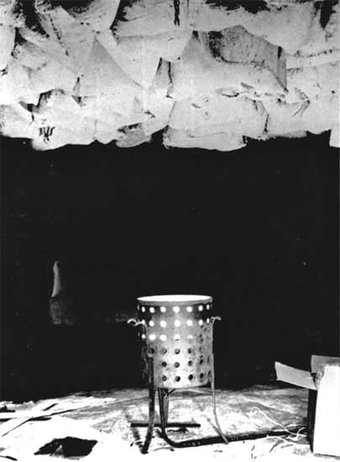

On the Tate website I read the following: “Duchamp hung 1,200 sacks of coal over the heads of visitors, which, although actually stuffed with newspaper, apparently leaked coal dust and must have been distinctly unnerving for those beneath. To add to this, the entire space was plunged in darkness. There were just two sources of light: a workman’s brazier, placed centrally in the exhibiting area, around which visitors huddled, and the flashlights that the artist Man Ray, Duchamp’s longstanding collaborator and the so-called ‘lighting advisor’ for the show, had provided to enable people to illuminate the works on display“

On the MoMa website I listened to an interview (video footage) and the following was said by a curator about Duchamp’s ambition, namely that for him it was not about how to be a better artist, it was about how to redefine the question of what it is to be an artist.

Kenneth Noland

In my research on the artist I read that he was inspired by stain painting (thin brushes of colour onto an unstained canvas) and his work was “championed” by the formalist art critics, like C Greenberg. He focussed on radiant targets made of rings of pure color strained directly on raw canvas which created a direct and vibrant colour experience for the viewer. I looked at his later work and I feel that this artist was not concerned with objects and narrative, and contemplation it was about painting and colour, pushing himself throughout his life. The viewer in this case, was getting an experience which required to walk around in the gallery – get use to the space these hangings was taking up and almost reflecting onto the viewer and how you as a viewer have to use your body around these works.

Ideas I am thinking about – contemplating the research question

I want to focus on the ‘shifts’ and keep it linked to the institution of the White Cube. As Schwitters was experimenting with collage and sculptures, he challenged the convention of how a piece of work can be displayed – perception changed, and it was motivated by investigating form and abstract thinking of cubism. One can say that Surrealism abandoned neutral exhibition spaces in favour of environments that embodied subjective ideologies. Apparently Duchamp saw painting as ‘retinal art’ and when he abandoned it, it was for a search of his questions about what is art, that he used his installations, where he in a sense took away that ‘eye of the viewer’ and showed the viewer the ‘brain’ of the artist, which is flowing with ideas, decisions being made, concepts, and not necessary only hard working crafting behind the scenes. I understand in hindsight how O’Doherty had the insight to see this and that it can be viewed as an almost foundation for conceptual art.

I am thinking about myself as a viewer of art – the need to critic myself around the spaces where I visit to see art – what to I embody in these spaces?

I am thinking if I made any ‘shifts’ in my own questions in my studio practice since I started with this course. I am thinking about the objects I paint or draw – are they in a way ready mades, ( concepts) by the fact that they exist as a memory, a fragment, discarded, exotic, scarce, endangered en dysfuntionalised? The question now becomes , do I make them into events when I link it with a walking practice. I would rather work with the ideas and research and experiment more with chance and improvisation and working in series (bodies of work) – as the learning and development of my own work with come with the process. (see Blog on Parallel project for Part 4)

Failure is an important consideration. In Experimental Painting, Stephen Bann considers a number of essays on historical painting and painters. One is Frank Stella, who he writes, moved away from external restrictions to encompass experimentation in his artistic practice and importantly produced his works ‘almost exclusively in series’ (Bann 1970: 64), an example of which is the Harran II (1967) series, shown below.

Stella felt that the classical approach to painting was alien to his method of working: ‘he sought unpredictability’ (Bann 1970: 64). He also suggests that the nearest comparison to Stella is not found in ‘the various types of pictorial experiment’, but in the literary and linguistic model offered by Roland Barthes’ (Bann 1970: 113).

According to Bann, Barthes was a public experimenter. To explain this idea further and Barthes’s reliance on theme and variations, which are evidenced as ‘new ranges of meaning when removed from the strictly temporal sequence which it implies’ (Bann 1970: 113) Bann said:

“the idea of variation may seem too limited to do justice to the

individuality of the works considered singly” (Bann 1970: 113).

This is a reference to the fact that most of Stella’s works are series, see above, and experiments as seen in the experimental drawings of this project. They are not considerations of chance, but of intentionality in the ideas about his practice. The concept of failure is also considered in the context of artistic practice.

I will also consider the ideas discussed by curator and writer Lisa Le Feuvre, the editor of Failure (2010), where she discusses failure in her reviews of a number contemporary artists in essays.

Manifesta 9, The European Biennial of Contemporary Art, 30 September, in Genk, Belgium.

Meecham, Pam and Sheldon, Julie, 2005 Modern art : a critical introduction Published by Routledge viewed online on OCA library, ebook Central.

O’Doherty, Brian,1986 Inside the White Cube: The ideology of the Gallery Space Essay series by Arts Berkley Edu.com accessed online on 3 November 2020 as a pdf document. https://arts.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/arc-of-life-ODoherty_Brian_Inside_the_White_Cube_The_Ideology_of_the_Gallery_Space.pdf

RESEARCH POINT 2

Research the work of Hans Haacke using the link below and other sources:

Hans Haacke: Exposing systems of power

http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/hans-haacke-2217/hans-haacke-exposing-systems-power

I started by listening to the video’s made available by Tate on 9 November 2020. Haacke is considered a pioneer of institutional critique and his conceptual works below aim to expose connections among money, art, and politics. In these videos he recounts that which inspired him to explore the relationships between art and the outside world in the following works:

- Condensation Cube 1963-5 – here the artist tries to show with plexi glass and water that art is like a living organism – it is an open system that continuously changes depending on its dialogue or interaction with the environment. It is not about the object, but the physical exchange in the environment , which is here the viewer and what he/she experience in the cube (gallery space) Kwon (2004,19) suggests that Haacke moves from the “physical condition of the gallery to the system of socioeconomic relations within which art and its institutional programming find their possibilities of being “

- A Breed Apart 1978. The artist look at the British Leyland company who supplied Apartheid South African defence force with landrovers, which was used in action against the rising Black majority. He used their own advertising slogan in this case, A Breed Apart in his black and white photos of real footage, which can be described as a ‘expose’ of the uprising – showing governments brutality against the Black people of the country. Clearly he wanted viewer to make these connections of business with ideology when they try to make sense of what one is exposed to when the site of art is an institutional frame work within economic and political terms.

- SFMOMA collection. 1969. – here he looks at anti establishment views in his generation, which were born shortly after the World Wars. Art was in a secluded space – he calls it a ‘holy sphere’, and he wanted to bring the real world, dirty politics, into this space – in this exhibition he was using the news of the day, being printed, as it was hooked up with a new paper agency – accumulating on the floor in the gallery.

I feel I should consider the following I read on this blog: “Post-structuralist art writing is not so much criticism as it does not “go after” any sort of final judgment of a work of art. This methodology of art examining is more interested in multiple interpretations, it advocates for individual evaluation more so than for objective analysis. In other words, post-structuralists reject any form of authority of inherited structures. Can I say that I understand that value of this form of critique lies in their descriptions and not in judgements? ”

Alberro (2009) discuss in their paper that the artistic practices of the late 1960s-1970s came to be referred to as institutional critique which revisited the radical promise of the European Enlightenment, and they did so “precisely by confronting the institution of art with the claim that it was not

sufficiently committed to, let alone realising or fulfilling, the pursuit of publicness that had brought it into being in the first place.” In this situation he continues the “artists juxtaposed in many ways the immanent,

normative (ideal) self- understanding of the art institution with the (material) actuality of the social relations that currently formed it.” By doing this it brought to the foreground tensions between the theoretical self- understanding of the institution of art and its actual practice of operation, and to summon the need for a resolution of that tension or contradiction. He looks at the analytical and political positions which were built into critical interpretive strategy. One can say that at that time even though these early critiques were juxtaposing the myths that the institution

it also perpetuated with the network of social and economic relationships that actually structure it: they ultimately advocated for the institution. Alberro writes that ” Haacke claims that they function as snares to capture the concealed machinations and assumptions of museums—as institutions, critique, and institutional critique “double- agents” that enter into the institution of art to show that much of what it presents as natural is actually historical and socially constructed. One understands here that the work of Haacke played a huge catalytic role – as a viewer one is confronted with the institutional practices when facing these work within the institution.

They refer to Belgium artist/poet, Marcel Broodthaers and work he did, A conversation with Freddy de Vree, 1969 where Broodthaers critiqued the hidden frame of the institution.

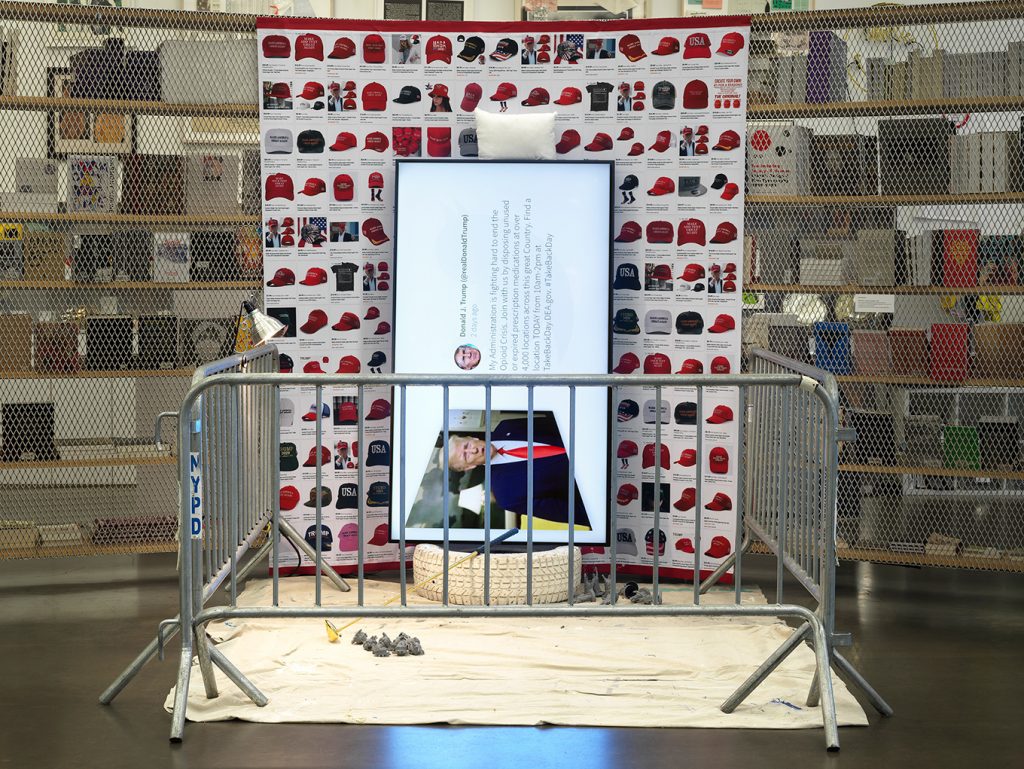

Below is a very recent work of the Haacke

In an article by Kastner about above exhibition he writes the following about Haacke : ” His practice has argued for more than half a century that, like the things we make, what we do and say should never be understood as discrete or dis-locatable from the world at large; all must be considered — scrutinized and critiqued — as implicated in the contexts — social, economic, political, historical, spatial, environmental — in which they are produced and encountered. The myriad outside factors that might affect our words and deeds are not always evident — in truth they are often obscure, and often so deliberately so — just as our own radius of action is difficult to accurately gauge. It’s precisely for these reasons that Haacke has so insistently made the case that the complex, interpenetrating systems that influence our expressions and behaviors deserve careful, critical investigation.“

Later I read that Kwon (2004,25) sees it as a move towards the dematerialization of the site as well as the simultaneous de- aestheticization and dematerialization of the art work – which continues to resist the commodification of art. Art became site-specific and adopted strategies which are antivisua – became informational, textual, expositional, didactic – one sees the relationship between work and site moves away from being based on the physical permanence of site. It is as if aesthetic and art historical concerns became secondary issues to real life issues of racism, sexism, homelessness, etc. Art works are now in hotels, city streets, housing projects, hospitals, schools, newspapers, television – the space expanded beyond the museum/gallery space system. Site is no more precondition. Since the late 1980, Kwon (2004.44) reminds that there have been increasing numbers of ‘traveling’ site-specific art works. We even see refabrications on site -specific works from the minimalist and post minimalist eras, becoming common again. Minimalist ideas of authorship and authenticity needs to be considered.

I recently read a critique on the work of installation artist, Daniel Buren – it was about a temporary installation of The Observatory of Light, in 2014 where a building of the Louis Vuitton Foundation, called The Fondation, is covered by colored filters—in 13 different hues—that accentuate the shiplike structure’s 12 billowing sails. One can see is as a true mastery of color and light, (these patterns refract on 3,600 pieces of glass both inside and outside of the building and create a kaleidoscopic effect that changes depending on the time of day and season) – but looking at the client, Louis Vuitton, a luxury fashion brand who took over this area, which has a cultural biography which dates back to when this park, known as the Bois de Boulogne park, acted as a cultural

The building acts as a center for art, music, and other cultural events It was the brainchild of Bernard Arnault, chairman and CEO of the French luxury-goods conglomerate LVMH Moët Hennessy–Louis Vuitton. “We wanted to present Paris with an extraordinary space for art and culture, and demonstrate daring and emotion by entrusting Frank Gehry with the construction of an iconic building for the 21st century,” Arnault said in a statement when the building was first built. This immersive installation is sure to dazzle the center’s visitors and passersby alike. (https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/frank-gehry-fondation-louis-vuitton-daniel-buren)

Alberro, Alexander, Stimson, Blake 2009, Institutions, Critique, and Institutional critique, Columbia edu

Kastner, Jeffery, August 2020 A System Is Not Imagined, Place Journal.org

Minton, Mellisa, 2016 Daniel Buren Brings Color to Frank Gehry’s Fondation Louis Vuitton, online publication in the Architectural Digest

Two videos on TATE :http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/hans-haacke-2217/hans-haacke-exposing-systems-power

RESEARCH POINT 3

Research the work of Fred Wilson and Mierle Laderman Ukeles using the links below and your own sources:

Reynolds write the following: “Hans Haacke utilized site specific critique of museums to expose systems within the museum, Mierle Laderman Ukeles used performance art to explore women’s labor and maintenance within the museum, and Fred Wilson used techniques of museology to present a new narrative within his work Mining The Museum (1991). Through analysis of these artists, their work, and their relationship to the Art Workers Coalition and the art world, the important role of the museum and its critique becomes clear. Critiques of the institution both in artworks and through political action are vital to the future of museums, as they are the holders of common culture and history. ” (Art Honors Thesis, 2012) Interestingly all three these artists are known for their conceptual art.

Ukeles Manifesto for Maintenance Art in 1969 was a performance of her doing work, which she called, MY WORKING WILL BE THE WORK (p146) As a first-time mother in 1969, she grew frustrated by the schism between her domestic life, (boredoms and joys), compared to her identity as a New York artist. She used this performance, a new medium of

artistic practice, to be critical of traditional artistic practices. Her Manifesto for Maintenance Art describes two basic systems of human labor: development and maintenance. She describes development as, “pure individual creation; the new change; progress, advance excitement, flight or fleeing. She wrote in four typewritten pages, how double standards exists in society pointing out a double standard; namely, that repetition and systems , like maintenance were considered rigorous in the context of the avant-garde, but dismissed as drudgery when it came to maintenance workers or housewives. I suggest it relates to feminism and the fact that museums of the past were largely responsible for not collecting the work of women and that the (art) work that women did was considered lower than fine art. I base that on the fact that the Art Workers Coalition’s formation coincided with the beginnings of the women’s liberation movement. The work also implies that cleaners inside the museum (working) are also important.

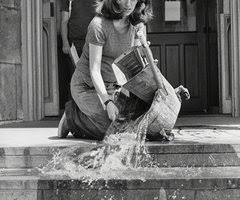

Her first public maintenance work was a set of four performances at the

Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford, Connecticut. The performances were called the Maintenance Art Performances and took place in 1973, in conjunction with a show of women artists curated by Lucy Lippard. The ‘actions’ took place over two days, Friday, July 20th and Sunday, July

22nd. Her cleaning materials consisted of water, stone, and diapers. Diapers were the material that conservators used for cleaning and maintaining objects. Ukeles work casued that they became a symbol of motherhood and maintenance. She called her motions ‘floor paintings, interesting one of the photographs Ukeles is pouring a bucket of water down the steps.

Kwon writes about this work as critique to the institution of art that the artist “posed the institution as a hierarchical system of labour relations and complicated the social gendered divisions between the notions of the public and the private (Kwon, 19) This act implied that art perceived in a literal space, diverged to a site.

A manifesto that was very effective was : “After the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?”

Scott, Andrea K, 2016 , Mierle Laderman Ukeles and the Art of Work , October 28, 2016 on http://www.mutualart.com/ExternalArticle/Mierle-Laderman-Ukeles-and-the-Art-of-Wo/CC6EB0C44D7405C2?source_page=Artist%5CArticles

Kwon, Mivon One Place after Another https://monoskop.org/images/d/d3/Kwon_Miwon_One_Place_after_Another_Site-Specific_Art_and_Locational_Identity.pdf

Reynolds M, 2012, Ethics and Exclusions in the Museum: The Art Workers Coalition and Case Studies of Institutional Critique, University of Colorado Boulder, accessed as pdf on 22 December 2020.

‘Fred Wilson’

Fred Wilson’s 1992 work entitled Mining the Museum, looked at an African-American narrative is as much as how the traditional museums were relying on the white male frame. I read that he was born in the Bronx in 1954 to an African-American father and a mother from the West Indies, and identified as African-American and Native American. Through working at a museum, he realised how the Black art community was not represented.

It seem that Wilson reconfigured museum collections – in above work he created juxtapositions that critiqued not only the museum, but also historical, political, and social structures of racial and social inequities, and even tying the movement to the emerging narratives of Identity politics in the art world. I read that art historian Jennifer A. González wrote about work of F Wilson as emphasing the visual history of race as a social discourse. “The collection and display of bodies, images, and artifacts in museums and elsewhere is a primary means by which a nation tells the story of its past and locates the cultures of its citizens in the present.”

The art market was also becoming globalised.

Reflecting:

Artist’s critiques of Haacke, Ukeles, and Wilson invited the art world to reflect on the history of the museum, how and what narrative is presented and new narratives they were inspired to include.

The Art Story.org Institutional Critique (Jeniffer A Gonzalez quote)

Archivesandcreativepractice.com [online] At:

http://www.archivesandcreativepractice.com/fred-wilson/ (Accessed on 19.07.18)

Garfield, D, Wilson, F (1993) In: Museum News (193) [online] At:

https://msu.edu/course/ha/452/wilsoninterview.htm (Accessed on 19.07.18)

Steinhauer, J. (2017) ‘How Mierle Laderman Ukeles Turned Maintenance Work into Art’ In: Hyperallergic 10.02.17 [online] At:

https://hyperallergic.com/355255/how-mierle-laderman-ukeles-turned-maintenance-workinto-art/ (Accessed on 19.07.18)

Ukeles, M L. ‘Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969’ In: Arnolfini.org.uk [online] At:

https://www.arnolfini.org.uk/blog/manifesto-for-maintenance-art-1969 (Accessed on 19.07.18)

RESEARCH POINT 4

Richard Serra famously asserted that his 120-foot Cor-Ten steel sculpture Tilted Arc made for the Federal Plaza could not be relocated as this would destroy the work. Research the sculpture and the controversy surrounding it.

The sculpture and the controversy surrounding it:

The Tilted Arc (1981) was a sculpture of monumental size which intimidated its site, the Federal Plaza in Lower Manhattan – the surrounding buildings as well as the people who worked in this area. It was a commissioned work for the Federal government (GSA) for permanent installation in Federal Plaza. After about a year of drafts and interviews, being chosen by a panel (government private appointees like art historians) reviews by both art-world appointed civilians and government officials, Serra installed Tilted Arc. He was invited to the White House to be congratulated on the work after the installation. Two months after its installation, a petition requesting the removal of the sculpture was signed by 1,300 federal employees working in and around the plaza. Outspoken critics included the architect of the Javits Building, Alfred Easton Poor, and William Diamond, the regional administrator of the GSA.

Tilted Arc

General William Tecumseh Sherman on the Army Plaza

Replacement work

If one looks at the historical and political situation at that time, it was in the Ronald Reagan era – and his appointee in 1985 convened a public hearing which led to the eventual court decision to remove and break it up. So we have the same people that commissioned the work arguing for its removal and finally succeed. Making is even more controversial is that in spite of the fact that 122 people spoke in favour of the Tilted Arc and 58 against, the jury voted to remove the sculpture. One could see it as part of the culture wars of the Reagan years. It seems most of the claims against the work was outrageous – like it caused a rat problem and security hazard, bombs can be blasted! The main public criticism was that the sculpture had a generally disruptive nature; its scale and location obstructed views and making it difficult for pedestrians and office workers to commute between buildings. Its overwhelming size and mass was aesthetically unpleasing to many and some felt that Serra had destroyed the work of another artist (the plaza designers) for his own artistic conceit. In the podcast Serra shares his skepticism that everyone in the community was against the sculpture. He lived within four blocks of the plaza for almost 20 years, and he saw the site as not just an areas used by federal workers, but as a place where international tourists and local residents interacted, gathered, and participated.

“The viewer becomes aware of himself and of his movement through the plaza. As he moves, the sculpture changes. Contraction and expansion of the sculpture result from the viewer’s movement. Step by step the perception not only of the sculpture but of the entire environment changes.“

More than 180 people spoke at the hearing and it became quite a media frenzy, with Serra even receiving death threats over the phone.

Other comments:

“Tilted arc has a proprietary claim on the plaza, just as a painting has to its canvas”

Moma also disagreed with the fate of Tilted Arc. People working in the area had to walk around the installation as they had to move around to work, but it was also used by civilians visiting the governmental buildings. One get to the question of who was using/viewing this plaza and art – was it for the public or seems by the reaction of the government, it was only for ‘them’?

The fact that site-specific work could not be moved also posed a challenge to the growing commodification of art. Some of the works created for specific locations have since become iconic and artists and curators have had to decide whether they can be re-fabricated. If they can (some may no longer exist or be too fragile to move) under what conditions and what are the implications in terms of the originality, and authenticity of the piece? Write 200 words in your learning log.

Serra insists that the work can never be installed anywhere other than the Federal Plaza. Over the year the GSA has made attempts to reinstall the sculpture at an alternate location, but organisations have been reluctant to go against the wishes of the artist. As a result, Tilted Arc has remained in storage for the last 24 years. (wnyc.org)

“I don’t think it is the function of art to be pleasing….. Art is not democratic. It is not for the people.” Miwon Kwon wrote that Serra’s statement signals a crisis point for site specificity in term of the “version that would prioritise the physical inseparability between a work and its site of installation” (Kwon, 2002:26) She also points out in her essays that site specific work was now not only about site in a physical arena, but a political issue. Could it be that site specificity was embraced as an automatic signifier of ‘criticality’ or progressiveness of the artists, and that the political power was at play? The ownership was motivated on the fact that the work was a commission and belonged to the government. The work will always be known as a Serra piece – maybe even more, but we only have photographic images and anecdotal stories to prove its history and making.

Looking at the public one need again to be specific with the times, history: Crimp wrote the the public’s ignorance is an ‘enforced ignorance’ (Krauss, 42) the court clearly dismissed their voice. For Serra the work had to be experienced as material reality ( see the welding done onto the steel, revelations of his work process by the artist/maker)) in the place where it resides. It is art that is not for consumption, but for a viewer to become involved, spatially in a specific site. I consider that even outdoor exhibition spaces could be revealed (institutional critique) as constraining, by having ideological connotations, or overtones – a frame – not being neutral. The public at that stage has yet to learn about urban policies and how culture and art became part of this discourse – Kwon calls it, ‘spatial-cultural’ discourse. Clearly it was seen by the government officials, that the artist was not sensitive to the architect of the Plaza’s ideas (NewYork article)

It leaves one with questions about ownership when doing a commission work – this changed over the years with new laws. It also asks if public art has to be practical? / Can it be Provocative? Must it be Beautiful? Who are the viewers of public art? Who gets to have a say in the process of commissioning new art? I feel like taking another road and look at contemporary work – Jeff Koons and his commissioned (gift?) to France after the terrorist attack. Times have changed as well as the public opinion and position it takes on these matters.

Copy from the New York times article: “The public is not likely to forget having had no say in the existence of a huge, dominating sculpture that no one in and around Federal Plaza could escape. The art world is not likely to forget the metaphors of dirt and decay that continue to inform the Government and press response to a major American artist’s work. Serra is not likely to forget the promise that his sculpture would be permanent, which led him to make the most ambitious and absolute work he could.”

Artists in the city a wnyc.org Podcast of and interview by Jenny Dixon with Richard Serra https://www.wnyc.org/widgets/ondemand_player/wnyc/#file=/audio/json/335510/&share=1

Krauss Rosalind E. Richard Serra/Sculpture, R E Krauss, Essay by Douglas Crimp, Serra’s Public Sculpture: Redefining Site Speciticity (p41 -5 6)

Kwon, Miwon, 2002, One Place after another

Brenson, Michael, 1998 The Messy Saga of Tilted Arc Is Far From Over New York times, April 1989

RESEARCH POINT 5:

Transforming Place: Site and Locality in Contemporary Art video recordings. At:

https://www.tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/transforming-place-site-andlocality-contemporary-art-video-recordings (Accessed on 04.08.18)

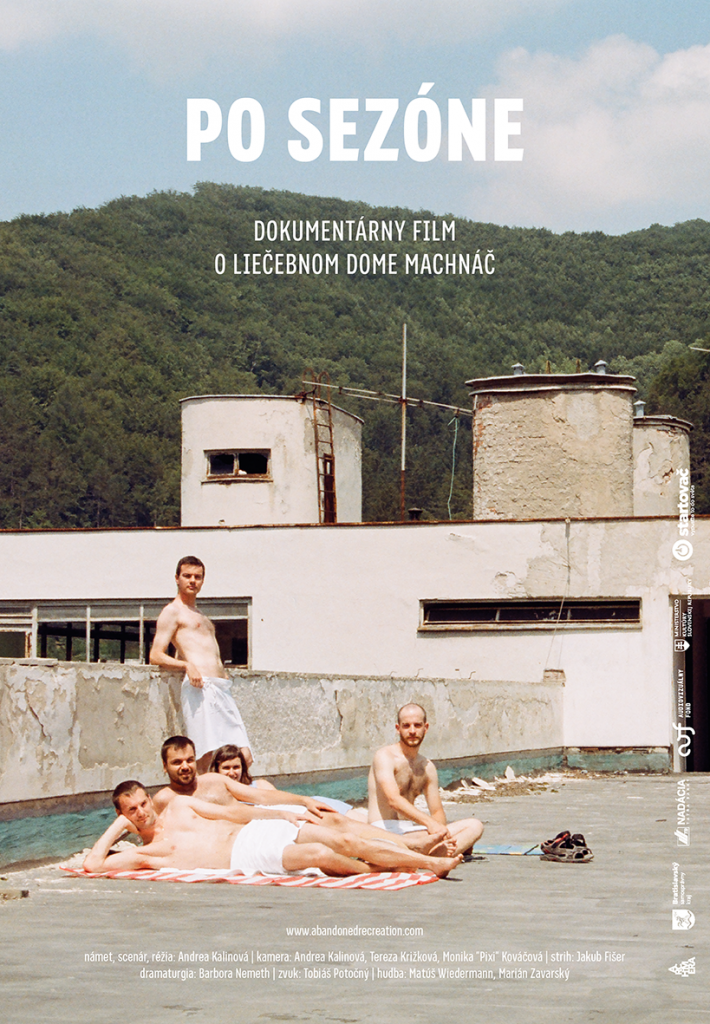

Look up Andrea Kalinová and Martin Zaiček’s Abandoned (re)creation and the work of Andrea Caretto and Raffaella Spagna.

Andrea Kalinova and Martin Zaicek:

This duo, architect and photographer started their ongoing project , they call it ‘long lasting’ in 2011 in the spa town of Trenčianske Teplice, current day Slovakia. Their first project was a sanatorium, the Machnáč which was an abandoned national heritage site of international value and became the main subject of several artistic and civic activities organised by them. Sanatorium Machnáč is described as an outstanding piece of the architect, Krejcar’s work, and it is considered to be one of the most valuable architectural buildings of the 20th century in Europe.

In 2014, they gradually started moving into other Slovak spa towns, where they researched and mapped the condition and value of the late modernist sanatoria, mostly designed in the 1960s and 1970s. The project resulted in the book where they focus on modernist architecture by creating new ways to engage with these buildings. On their website I read the following:” The title of the book ARCHITECTURE OF CARE reflects the phenomenon of balneology in the area of todays Slovakia in the period after WW2, and the way the human body, its regeneration and lifestyle was perceived at that time. The spa care was based on prevention to the development of illness. I find it interesting to read that the idea of collective recreation embodied in spa architecture represents the condensed ideal of socialist society. This attitude disappeared after 1989. Our present hectic lifestyle fails to afford enough time for our care of ourselves, medical care mostly deals with consequences.” Then when I read more I find that the current use of these buildings are for refugees: “Nevertheless, due to political, economic and social movements in the past 25 years Georgian spa architecture has undergone an extensive and a highly traumatic transformation. The war in Abkhazia in 1992-1993 lead to forced migration of over 200,000 ethnic Georgians from the Black Sea coastal separatist region of Abkhazia to Georgian inland. In trying to find a quick solution to the situation, many migrants have been temporarily moved to modernist hotels or spa resorts. The political crisis has, however, become a long-standing conflict lasting till this day. Thus, many of the migrants became permanent residents of facilities designed for institutionalized collective spa recreation. Many of the buildings were therefore rebuilt into collective residential quarters through random, participatory do-it-yourself processes.” The group has printed guidebooks with information about these buildings and walks around the town to visit the buildings.

In its initial two years, the project operated as a workshop for students and recent graduates, mostly from the Academy of Fine Arts and Design. The participants were supposed to respond to the dilapidated architecture by site-specific installations and interventions in the public space. It seems taht at least 10 artists partook in this project, which later developed in lectures in which the community also partook. A documentary film of Machnac shows the decay of the building, and the fact that for the current owners it does not make financial sense to upkeep or restore it – it is becoming a ruin. In this video the last question is very strong: ‘what is dysfunctional, the building or the society. I get the idea that the problem lies with a memory which is being discarded – let to decay and die? How did the public react – do they care? As activist and commenting on socio cultural issues these artist have created a different work process in art. I did a quick google search and found that the city is still famous for its healing waters and modern day spas.

On the website of the city I read the following: The greatest merit to the development of the spa in Trenčianske Teplice is attributed to the llésházy family who owned the spa for 241 years. At that time, it was one of the most important spas in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire.

In 1835, the spa was bought by the Viennese financier George Sina, who rebuilt and modernized it. His son Simon built a hotel and expanded the spa park. In 1888, his daughter Iphigenia had the most valuable historical monument preserved to this day, the Hammam spa in oriental Moorish style, built next to the mirror room Sina

Interesting that here is nothing written about the spas of the Modernist style during the communist era on websites about the city.

Looking at these decaying buildings, I cannot help but think of a visit to Barcelona two years ago – I did a walking tour, focussed on the modernist buildings in the city centre. These tours are popular, educational and enjoyable – I felt there was pride in the history of these buildings, the tour guide was well trained and shared many of the architectural history of these buildings.

http://www.abandonedrecreation.com/english-summary (Accessed on 20 December 2020)

Andrea Caretto and Raffaella Spagna.

Project Marta is a monitoring art archive to aid projects that specialize in the conservation of art work – by creating this data base, professionals are at hand to assist in restoration, preservation and promotion of cultural heritage by creating multimedia materials for education and outreach. It is a constantly growing research source and a comprehensive benchmark to do conservation of contemporary artwork as well as managing various materials involved in art by contemporary artists. Andrea Caretto and Raffaella Spagna is a duo who worked on projects. I looked at one of their projects, Falis Frutti, 2015, which is an installation that presents the reproduction in wax of one hundred and five apples of an ancient traditional Piedmont variety. They were made from wax modeller Davide Furno, and the real fruit were used as moulds to create the artificial fruits, by using a technique developed by a late nineteenth century wax modeller Francis Garnier valets. This variety of apples does not exist any longer. It was very difficult to get much more information – on the website of projectmarta I copied this: …”“metal” apples are exhibited as they were sculptural objects on glass shelves. Caretto / Spagna invite the visitor to focus on the morphology of each variety, rather than on the colour of the fruit.

I read that here is strong links with the Arte Povera artistic movement: The focus is on food and care for the land, as well as the social and natural landscape. The outcome is to foster solidarity and social inclusion.

I was very interested in the work done by these community driven projects – and looked into Cittadelarte and Let Eat Bi, which is also part of the group with whom the artists did above project. They work at forming partnerships in the community, with associations, cooperatives, social enterprises, economic operators and local communities, aggregates, promotes and contributes to organizing resources and activities (knowledge, actions, planning ) operating in the Biella area whose common denominator is the care of the land, of the social and natural landscape.

The focus is on outcomes that produce culture, conviviality and sustainable economic development, promoting social inclusion. Interesting was their project about land use for agriculture.

I could not get good information behind the why of the The Anthill Village was a collective action of digging out and auto construction of raw earth laid and was run in the form of a workshop 25th-26th June 2005 c/o Munlab, Ecomuseum of Clay, Cambiano (To), Cambiano clay quarry.

Participants: Cesario Carena, Andrea Caretto, Silvia Casetta, Paola Gaeta, Pierluigi Gamba, Grazia Isoardi, Gabriella Moltoni, Carmine Morano, Cristina Morano, Luciano Perissinotto, Francesca Piana, Assunta Picone, Raffaella Spagna, Davide Toniolo, Nadia Tozzoli

I feel there is a lot to learn from them for when I am back in SA. I joined the group and looked at current projects, but they are not currently doing anything in Southern Africa. I will continue to read their newsletters and follow them on social media. The project, called “Terre Abban” interested me particularly. It is a project which intends to restore uncultivated or abandoned lands in the Biella area to their agricultural vocation, promoting exchange and dialogue between the inhabitants and at the same time trying to stem episodes of abandonment and degradation of the rural landscape. Their efforts are to get cooperation within the local community, developing a sensitivity aimed at reuse rather than consumption, the care of the territory as a place of collective identity also pass through making available a forgotten land. The vision of the project is to make the Biella area a place for experimenting with good practices of participation and sharing, as well as for the enhancement of the rural landscape.

I enjoy how the work informs histories which could be lost as well as connect with current day farmers and consumers. I see potential for my own ideas within such a form of project when we move back to SA in April 2021. Our community is a farming community, social issues are linked to poor communities, with less access to land ownership and social status. The historical background of the town is closely linked to colonialism and Apartheid – farms belong to white families and workers are Black and brown people living in the area in poor social circumstances. Artists in the town have started community driven projects and I will surely join in.

In Kwon ( 2004,26) she writes about artist exploring non-art spaces and touching onto disciplines such as sociology, political theory, etc., and site moved into a wider cultural landscape (Kwon 2004, 52) – work are in neighbourhoods, a theoretical concept, a historical condition – resists commodification and engage with marginal groups/places – as the artist become more of a service to the community.

http://www.projectmarta.com/en/autore/andrea-caretto-raffaella-spagna/ Accessed on 16 December 2020

Project Terre Abban http://mappa.italiachecambia.org/scheda/let-eat-bi-il-terzo-paradiso-in-terra-biellese/

“The place where [language] communicates best and most easily is also the place where[it] is the least interesting and emotionally involving […]

When these functional edges are explored, however, other areas of your mind make you aware of language potential. I think the point where language starts to break down as a useful tool for communication is the same edge where poetry or art occurs.”

— Bruce Nauman (

Christoffer Cordes, ‘Talking with Bruce Nauman: An Interview, 1989’ (excerpts from interviews: July, 1977; September, 2

1980; May, 1982; and July, 1989), in: Janet Kraynak (ed.), Please Pay Attention Please: Bruce Nauman’s Words.

Writings and Interviews, Cambridge/London, 2003, pp. 354-355

As artists have moved further into the wider cultural landscape away from the spaces and institutions of art, the site can now be ‘different cultural debates, a theoretical concept, a social issue, a political problem, an institutional framework (not necessarily an art institution) a neighbourhood or seasonal event, a historical condition, even particular formations of desire are deemed to function as sites.’ (Kwon, 2004: 28-29) Whilst earlier site-specific work was fixed to a location, today it is fluid, ephemeral and even virtual. Kwon asserts that the discursive site recasts the role of the artist as author and as central to the work, in order for the work to be authentically repeatable. Although the work has dematerialised and resists commodification, as institutions and public bodies line up to commission artists to engage marginalised groups/ histories/places, the artist now becomes a service/commodity. Once a piece is regarded

successful an artist may be asked to apply the ‘same treatment’ to another situation or plac