RESEARCH POINT 1

Look up interviews with and texts about the British artist Lubaina Himid and Kerry James Marchall. ( Study material offers suggestions of youtube video to listen to, as well as other online sites, such as MOCA) I am asked to reflect in my learning log in writing or in the form of an audio piece on how these two interviews differ from the experience of reading a text about an artist or their work. (interesting that I have started listening to audio discussions recently) I firstly want to familiarize myself with the artists and their works.

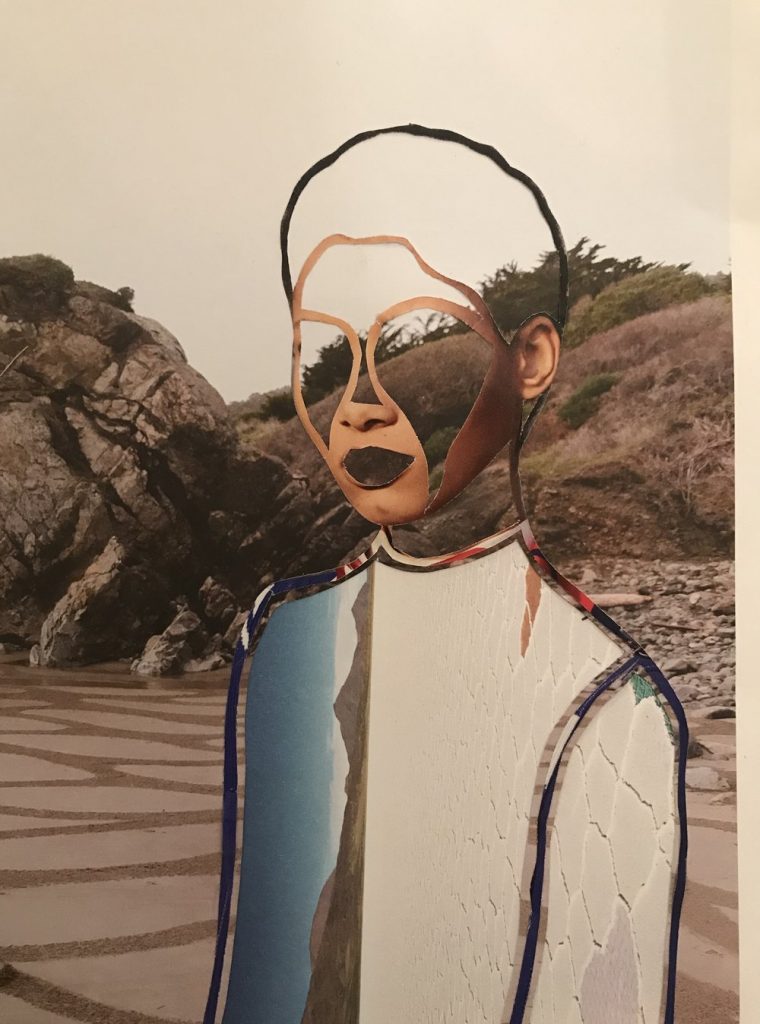

Tate Shots video (Lubaina Himid – ‘I’m a Painter and a Cultural Activist’ . June 2018) with the artist Lubaina Himid talking – her childhood (mom a textile artists learning her to look at things) influences and training in theatre as a designer of sets, her thesis as a student and awareness of ‘invisibility’ of young Black (women) artists, but not experiencing Black woman as a ‘solid group’. Painting is about filling in the gaps, using found objects and paint a history on them – that which is not talked about so much. It is about getting into the space of the viewer, her cut outs. She feels she can see two things at once – being between 2 things, like race, or divide yourself between the two things. She wants to have conversations with her viewers – history or experience happening in these public spaces where art is. She feels strong about ‘belonging’ and contributions to cultural landscape to be shown and seen. She looked a lot at William Hogarth in terms of art history and tell her stories about the slave trade. Above work, Carrot Piece, refers to a time where Black artists were invited into institutions, with main reason being funding, and this artist saw the ‘gap’ by partaking in this institutional ‘game’ – because she felt that after she made a work – the work has to ‘do’ something, ‘talk to’ viewers, and this space was then seen as appropriate . She sees her work as shifting ideas – act of negotiation, reasoning – brokering of a deal. (Then I read this on the TATE website: “Himid says that when the work was made, cultural institutions ‘needed to be seen’ to be integrating black people into their programmes and ‘we as black women understood how we were being patronised … to be cajoled and distracted by silly games and pointless offers. We understood, but we knew what sustained us… and what we really needed to make a positive cultural contribution: self-belief, inherited wisdom, education and love.’

Below is her work, Naming the Money where she tells the story of slave/servant and emigrant and asylum seeker, one which is often revealed in art, as the figures are not important or just being there as supporting and to enhance the appearance of the owner/master/mistress.

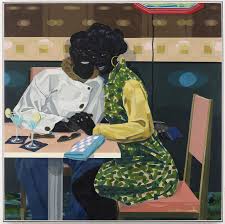

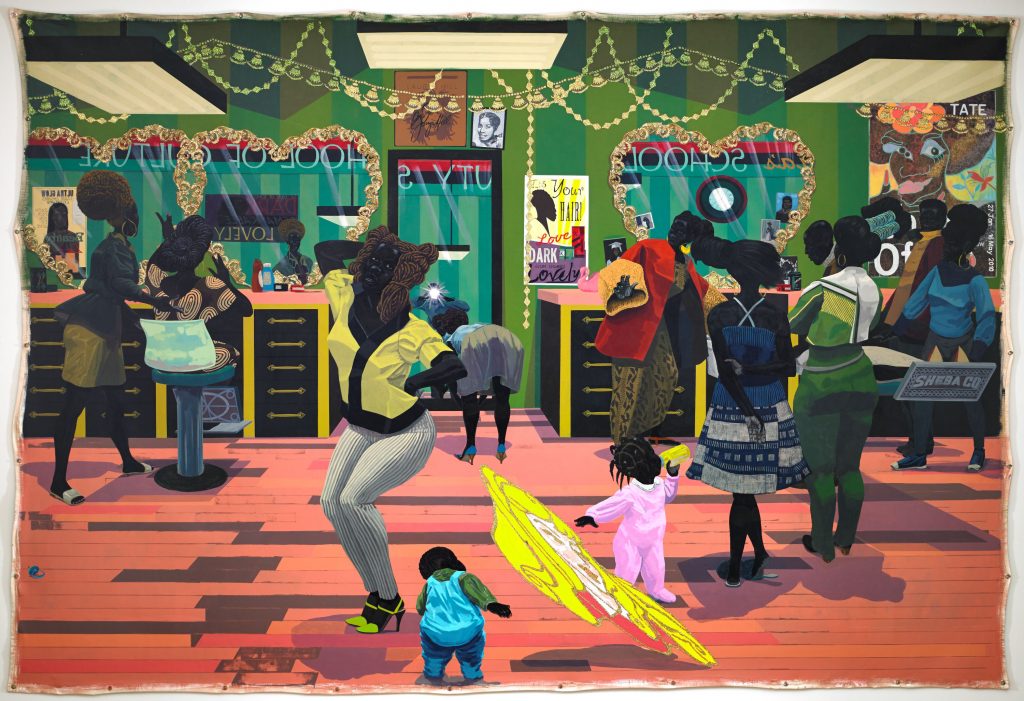

Looking at Kerry James Marshall I realize he is a ‘pictures generation’ artist, like Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman……., a Black male artist and thrown into the social movements of his era. By the early 80’s he commits to painting using exclusively black figures, and calls it unapologetically, Black, by choice of dark colours of the figures he painted, becomes about colour, an identity, an aesthetic, a philosophy, as Helen Molesworth stated, it gets to be a ‘way of being’ (video of Moca). One has these beautiful executed works, but become aware of a gaze from the subjects to you as a viewer – which becomes the complicated narrative in his work.

De Style, acrylic and collage on canvas, 1993

I was excited to find a recent Tate talk by artist, Sharon Walters on Instagram – my interest was heightened when I heard that she is inspired by Labaina Himid and that apart from showing her own work and workprocess she would talk about The Carrot piece. She interprets The Carrot Piece in an empowering and personal way, as she recently stopped to work for an art institution, and work full time on her art. She she the woman as having her hands full, to demonstrate that she has everything that she needs, despite what the institution is trying to through at her . She sees the power dynamics at play – is it as a sign of the constant battle?

She referred to her latest series of work called Seeing Ourselves’ where she explores under-representation in many arenas in particular, the arts and heritage sector and mainstream western media. She works mostly with cut outs and collage as medium for her work. Below are two of her works.

My Reflection on above works of the two artists:

I think my own feelings to belong can link with these narratives. I realise my longing to be among people where I feel at home – culturally and physically in a place where I am acknowledge as being part of, and not ‘the other’. I can also recall the history of South Africa and the effects of Apartheid as ideology for the ruling White minority after being a colony. Living in a place where you are seen or treated as an outsider, due to not becoming or allowed to become part of the place can really be a hard space for humans – we need to socially integrate and feel connected. I feel this is a history we need to be open to learn from in order to create open and non discriminatory societies. Art history has many narratives where these stories were hidden within the works.

I am also asking, how do one ‘reclaim’ identities without power (as its is so easy to corrupt) – I think these artists shows power within their art by focussing the viewer on the expression of the silenced within history of art, culture and society. Feeling at home within myself, a place, within a community, as part of a cultural group needs to start by opening up conversations to exactly these things and claiming it back. How is it possible that someone can lose his name – is this driven by the powers of money, or what does it say about humanity?

Reference lists

Naming the Money WordPress blog of Lubaina Himid (lubainahimid.uk)

Lubaina Himid: Turner Prize 2017 [online] At:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PKiN2FHqYFU

Helen Molesworth on the work of Kerry James Marshall: https://www.moca.org/exhibition/kerry-james-marshall-mastry (accessed on 23/01/2021)

Listen to the discussion between Kerry James Marshall and Helen Molesworth at The Museum of Contemporary Art. If you cannot access it, find an alternative interview, or text regarding the work of Kerry James Marshall. Kerry James Marshall and Helen Molesworth in Conversation [online] At:

https://www.moca.org/program/kerry-james-marshall-and-helen-molesworth-in-conversation (Accessed on 22/01/2021)

Reflect in your learning log in writing or in the form of an audio piece on how these two interviews differ from the experience of reading a text about an artist or their work

https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucreative-ebooks/reader.action?docID=4535042&ppg=11

RESEARCH POINT 2

You examined attempts by fluxus artists to challenge the status quo in the previous topic. Look up the ways in which Dada and the Situationists made provocations.

Situationists: ” In his Report on the Construction of Situations (1957), the manifesto of the movement, Debord wrote that “Our central idea is the construction of situations…We must develop a systematic intervention based on the complex factors of two components in perpetual interaction: the material environment of life and the behaviors which that environment gives rise to and which radically transform it”. (theartstory.org) From what I understand the Situationists (SI) privileged writing of manifestos over the production of art works: they did not want to be part of a historical avant-garde, whose provocative art had been co-opted by the cultural establishment.

They used a form of ‘vandalism’ and kitsch to critique the institutions. I will show images to confirm this ideas:

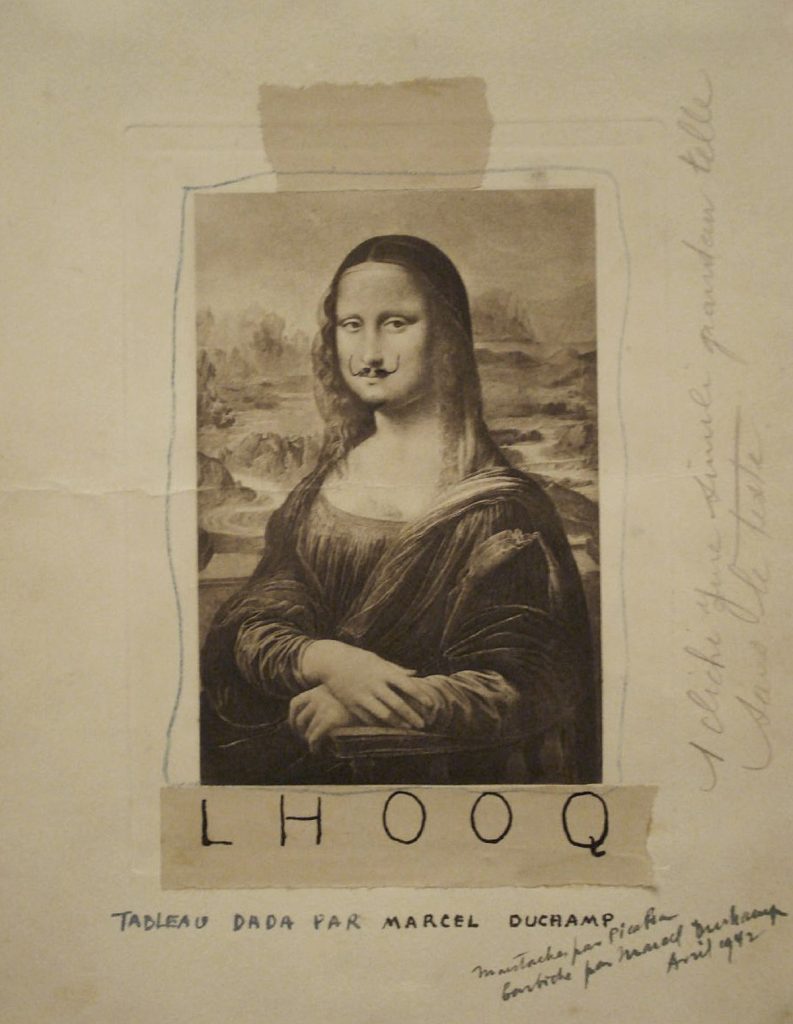

It seems that Duchamp’s Mona Lisa is meant to be seen as a Freudian joke. But this is not merely an allusion to Freud, here he reveals with his gesture (vandalism) that which the painting conceals, by uncovering an ambiguity of gender at the heart of Leonardo’s aesthetic – could Leonardo have seen the male form in the female.? Is this a hidden self portrait by Leonardo da Vinci? One is also aware of how banal reproduction of these works had become, one can buy it being printed on almost anything from clothing to a printed replica.

Jorn Asger led the movement artistically, with Debord its leading theorist. His concepts of psychogeography, dérive and détournement, as well as his view that the existing social system was based upon the “spectacle” and the “commodity”, informed the group’s mission to create a new artistic paradigm in the early 1960s. Guy Debord joined the Lettrist movement in France. The movement took its name from “lettrie” (letters) which were viewed as pure form devoid of semantic meaning. Lettrism was founded by Isidore Isou, who was again influenced by Dada and Surrealist: Isou emphasised combining poetry with graphics and experimental film to create controversial juxtapositions. Situationism strongly influenced Performance and Installation art of the Fluxus artists. The movement’s style and slogans were also adopted by 1970s punk rock music and other musicians, including Laetitia Sadier, Chumbawamba, David Bowie, and Nation of Ulysses, and the 1990s hardcore punk of Orchid, CrimetheInc, and His Hero is Gone. Digital phone apps like Drift, Random GPS, and Derive, have also been developed, as a way of experiencing Situationist drift. (see my Parallel project) One can consider to see their pioneering use of political graffiti to critique commodity culture as setting the groundwork for many subsequent artists, like graffiti artist Banksy.

It seems that the late 1950s were given over to the creation of an artistic revolutionary praxis (applying theory and philosophy in everyday life), as the SI began staging interventions in the art world.

- In 1958 they “raided” a Belgium art conference by dropping pamphlets and using extensive media coverage to critique the social system of the art work

- Wildcat strikes and riots in Paris in May 1968

- Shortly after the May ’68 riots, there were a number of demonstrations in London against the American involvement in the Vietnam War, centred on the American Embassy in Grosvenor Square.

Research point 3:

The work Untitled, (public sculpture for a redundant space), 2016 by Mike Nelson, consists of a prototype for a series of three works made on site for the High Line in New York. The High Line is a former elevated railway line that once fed the industries of the western edge of Manhattan. These are long defunct, like most of the industries that once thrived in the area.

Any signs of this recent past will disappear once the redevelopment of the former factories and warehouses is completed. For this work in New York Nelson uses the rubble from these sites to fill sleeping bags; at the Royal Academy in London, the sculpture contains debris from a site close to Nelson’s London studio. After conducting your own research, write a short review of this work in your learning log.

It clearly looked like a homeless person’s sleeping bag; something abandoned/rubbish, or even a crime scene. ( In South Africa – people will complain as this is a public park, made for walking, and this object can indicate that the area is unsafe!) The artist won the 2018 Charles Wollaston award for the “most distinguished work” in the Summer Exhibition. Above work is described by the ‘most distinguished’ – very interesting and great if one understands the context and look at the space surrounding the work. Being a walker I can identify on so many levels with this work – it would be something I would have loved to thought out this as an installation myself! I have considered if it would be ‘appropriate’ to make a work with the rubble, plastic and other junk I find outside when I walk. The images below connects with cities, development and redevelopment – here where I live, building rubble is lying outside our compound – I have collected many images of stuff found, see below.

As with the work of Nelson I relate to the mess people leave behind – be it after a work was done, or just being inconsiderate to get rid of rubbish in the ‘correct way’ – by taking it to a dustbin or landfill. Evidence of our being in a place is not always something aesthetically pleasing or to even be proud of and want to keep as a memory. Here in Dubai cleaning is done by municipal employees and it is sometimes hard to comprehend why people do not clean up after themselves. I also felt that I challenged my judgement of ‘homeless’ people who live on the streets – it cannot just be a mere nuisance which drives the frustration toward this problem. I find it hard to imagine not having a safe home, as least a safe place to sleep in every night of my life. What does it feel like and do to a person to have ‘home insecurity’? How important do I view people’s right to a home within society? Do we ever consider the enormous social problem homelessness is all over the world, and what to do about it and how to address it? I think about living ‘outside’ the norm – being seen as ‘useless, a threat to safety and sense of gentleness of a living space – is this too complicated to think about this relationship that exists in our cities, and play out under bridges, on streets, public park (benches) and in shelters? Is it touching my own ideas of place and its aesthetics, but also the unequal economics that we created? It is a well known fact that property value is linked to a factor like being close to a shelter or low cost housing. Again these works lead me to think about the vulnerable, the side-lined, the other – this time it is mostly a judgement on economics and social status.

I know that with the Covid Pandemic and lockdown period, many people lost their jobs – here in Dubai people could not afford to fly back to their home countries (rule is that you have to leave the country within 30 days of being jobless) Shelters are available, but I could not find good information about the operations and or numbers of people living in these facilities.

RESEARCH POINT 4

Look up the works by the artists below and consider the kinds of concerns the work is addressing, how visual language is adapted to communicate them and the relationship between the form and the subject/content? How much does the artist rely upon the power of the visual to convince the viewer?

Research Jananne Al-Ani, Shadow Sites, 2010.

Research Amie Siegel, Quarry, 2015.

Research Shilpa Gupta, In your tongue, I can not fit, 2018.

I have seen the work of Shilpa Gupta in 2019 at the Venice Biennale and was really touched by this haunting work. She raises concerns about our right to freedom of expression, mostly the bravery of those who struggled to resist. One encounter 100 microphones suspended of 100 metal rods, each piercing a verse of poetry, with a name of a poet who have been jailed through time for their writing or their beliefs. Sound is used over microphones to recite fragments of these poems. First one hear a single voice, then it becomes echoed by a chorus which shifts across the space of the installation. Reading these works, whilst moving through the installation was powerful to experience the power of poetry to counter dominant political doctrines over different times and geographies. One is so aware of the struggle of so many people, a reality of it today due to the lack of democracy and human rights which exists in many social and political situations around the world.

I believe in the power of words as part of transformation, and this work came very strong in this way. This artist makes notations of the things that concern her. In the video below she talks about this installation.

I read the following about her after an exhibition of her work, Thought Inside a Thought (2017) in the Juliet Art Magazine. The work can be described as a circular neon sculpture in which the words of the title follow each other without interruption.) The work plays with the idea of intersubjectivity and with the fact that all our thoughts come from within us but are not yet completely ours: they take shape in the subconscious in precise times and places, but they never completely coincide with the moment when they emerge.

As the artist states in the interview with Monelli , “I am constantly attracted by perception, and therefore by definitions, and by the way in which they are forced or even transgressed”. Clearly the he structure of the work invites the spectator to participate by repeating aloud the words he/she reads to introject them as if they were a mantra and to be led by their persuasive repetition in the ‘unreadable’ place of thought caught in his being.

Monelli, Philipo, 2019 https://www.juliet-artmagazine.com/en/shilpa-gupta-do-not-see-do-not-hear-do-not-speak-again/

Research point 5:

For some artists, art can be a way of living that affects every aspect of their life. The American artist, writer and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz lived a life that was inextricably connected to all forms of his creative work. Research these 3 strands of his output – artwork, writing, activism and describe in your learning log how they inform and affect each other.

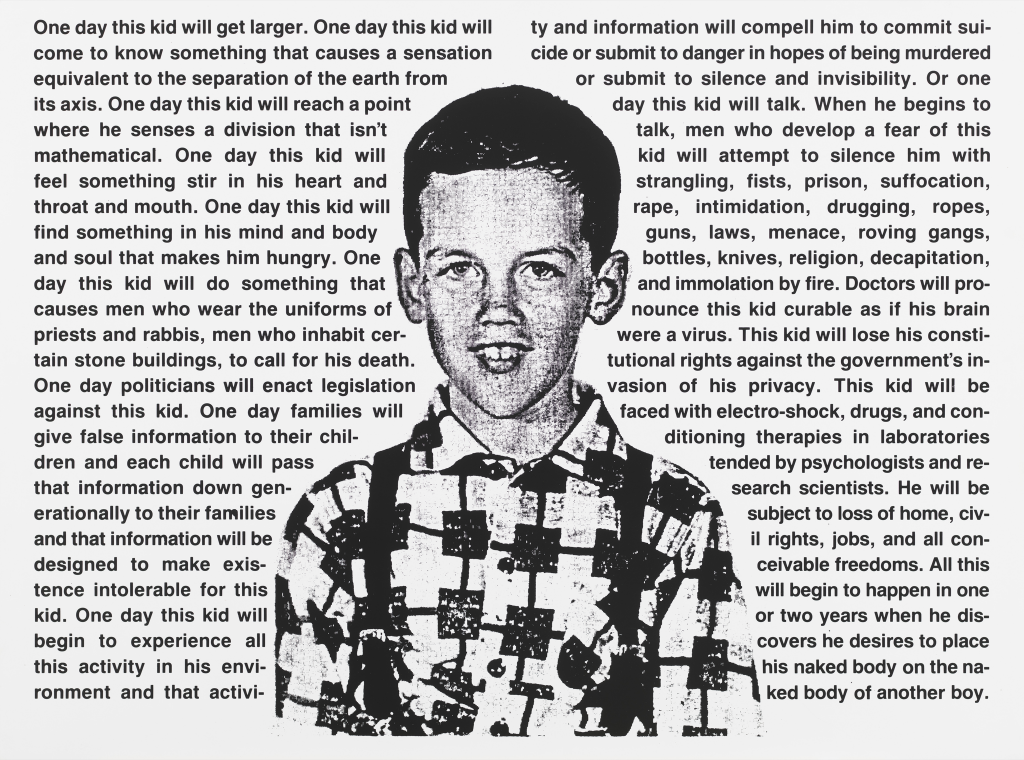

In this work, above, one has text, image, political action. Wojnarowicz did this for his 1990 retrospective, Tongues of Flame. Above image is from a retrospective at the Whitney Museum, stating ” the life and work of the artist and AIDS activist are a model for making art out of political anger”.

A New York Times article sums up this work very well: “Twenty-five years on, it remains a powerful statement about innocence, shame, hate, homophobia and the dangers posed to individual liberty by repressive governments. Like many of Wojnarowicz’s works, it mixes text and image, autobiography and political action, tenderness and rage. And as much as it says, it is more remarkable for what it doesn’t say. Wojnarowicz had received a diagnosis of AIDS before he made “One Day This Kid” (he died in 1992, at age 37), but the text makes no mention of the virus. It diagnoses a society, not an individual. If AIDS kills you, it says without saying, that’s only because America already wants you dead.”

Christine Smallwood 2018,The Rage and Tenderness of David Wojnarowicz’s Art , online published in New York Times magazine, published 18 September 2018. accessed on line on 2 February 2021

RESEARCH POINT 6

Look up the work of Adrian Piper

On the MoMA website I read the following: “Since the 1960s, this uncompromising artist and philosopher has explored the potential of Conceptual art—work in which the concepts behind the art takes precedence over the physical object—to challenge our assumptions about the social structures that shape the world around us. Often drawing from her personal and professional experiences, Piper’s influential work has directly addressed gender, race, xenophobia, and, more recently, social engagement and self-transcendence.” I then used a video (conference with the artist and curators at MoMA) to listen and learn more about her work. I enjoyed the videos she called Funk and how it explores dancing and ideas about black and white people’s conceptions of dance, as well as identity. She really gets her audience into these discussions and this makes her work very personal in terms of experience. The fact that she is a highly acclaimed academic scholar in philosophy made me look at her lectures and her understanding of the importance of artistic research and keeping it sustainable by having an online archive. She shares personal and subjective views, but it is driven by evidence of years worth of research. In her much of her installation work, called she confronts the viewer with making choices/decisions – she does not judge, but she asks of viewers to think about their ideas and decisions. There is the work called the Humming Room, where you have to hum or another where you have to sign a statement…. . The viewer is pulled into the work very effectively., and it is as if the work touch our being, we are asked to commit, never be just an onlooker with no viewpoint, a very personal experience.

I can take so much learning from this artist for my own practice – how I engage and connect with viewers. Art is not passive – we cannot be innocent bystanders. I want to go back to my rhino drawings – having a space somewhere in an exhibition where viewers are ask to sign a statement, give a commitment to their views on trade of rhino horn. I also think of my walking audios and how my friends reacted when starting to make their own sound recordings or reflections of a walk experience – seeing and experiencing on a deeper level – looking more closely…

moma.org

Research point 7:

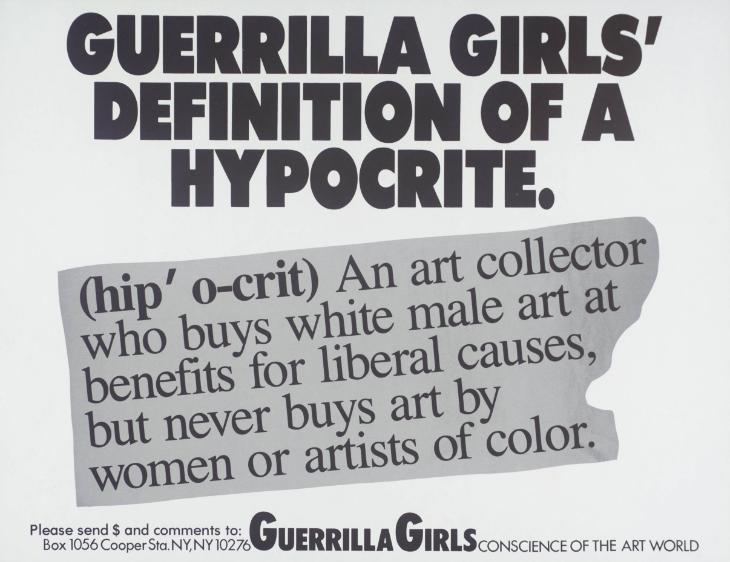

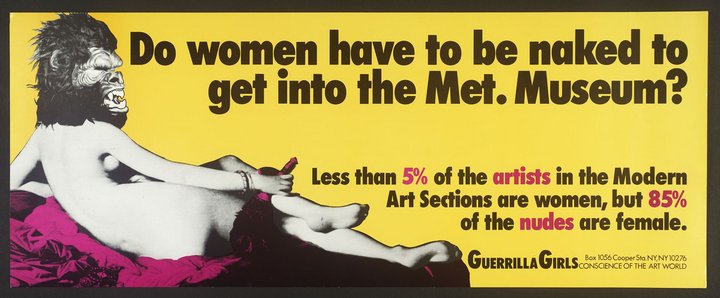

Look up the work of the anonymous female collective the Guerrilla Girls.

I listened to an interview with the Guerrilla Girls, presented by the Hirshhorn Gallery – it was a Zoom talk on January 27 2021 at 7:00 US eastern time, which I could view afterwards on YouTue channel. The interview was called, On Art and Behaving Badly.

They have become a group of very diverse woman – including skin colour and sexual/gender. They see their work as part of their artistic practice, working as a collective. I like the idea of staying anonymous and focussing on issues, rather that personalities or individual work. When in public they wear gorilla masks and name themselves after famous dead women.

What I took away from their idea to take their activism to the streets and take on the ‘gate keepers’ within the art world, has developed with time. From posters to using the current technology of today – namely digital printing. I follow them on Instagram and feel they are very relevant and not shying away from injustices and still focusing on critiquing culture. and how people are excluded. Although they began as an activist group, they have gradually been embraced by the artworld and have shown their work in galleries such as MoMa and Tate Modern. I remember viewing their poster work inside a museum in Barcelona a view years ago (2018) – institutional biases are clearly addressed by them ‘making trouble’. I also think this type of action show how many people they reach, and leave us (viewers) with critical questions to ask: like seeing how the art world became more and more and instrument of capitalism, and or with art becoming a trade commodity for rich people.

When thinking about direct action I really could walk away with many questions I feel I can address in my work, by asking the questions about art and how power seem to control decisions, which should be questioned. I agree that the world needs more groups like theirs, as one need to look at this work and ongoing. I also think the ideas on transformation, comes back to a continuous process of growth and new realizations.

One can also question the functionality of the museum space – why can it not serve by repurposing its space when it is closed at night – live up to its social function?

Research point 8:

One of the projects commissioned by Sculpture Chicago’s Culture in Action –

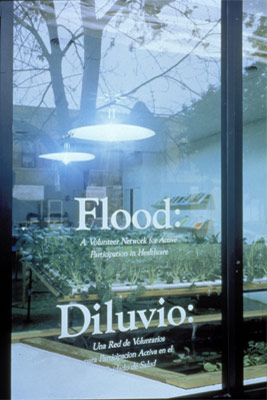

HAHA: FLOOD, 1992-1995 was initiated by artists Richard House, Wendy Jacobs, Laurie Palmer and John Ploof who formed a volunteer team. Research the project and consider why it has had a lasting legacy.

This volunteer network focussed on active participation in Healthcare, when they built and maintained a hydroponic garden in a storefront on the north side of Chicago. Here they grew vegetables (kale, collards, mustard greens, swiss chard) as well as therapeutic herbs for people with HIV. For several years Flood provided bi-weekly meals, educational activities, meeting space, public events, and information on alternative therapies, HIV/AIDS services in Chicago, nutrition and horticulture, as well as a place to garden. The storefront closed in 1995, but this initiative was instrumental as a future-directed seed project. They volunteered at social service organizations and hosted a series of round-table discussions between social service and community-integrated organizations. As a result, a collective effort emerged to build a comprehensive HIV/AIDS facility in Rogers Park, which opened in 1997. This facility contains a food pantry, an alternative high school, a community center, and administrative offices for four organizations.

Looking at how the current Covid pandemic has struck communities all over the world, this project provides a great case study for thinking about the role of artists and collectives: it focus on ways we can be integrating life with art.

Research point 10:

The Austrian art group WochenKlausur is a collective that since 1993 generate what they call “concrete interventions” using funds provided by various cultural institutions, to initiate long‐ term, problem‐solving measures in the local communities. Research their interventions.