7 June 2018

Research Point

Research artists from different eras who use landscape as their main subject.

I read that in Italian a Vedutista, is a Landscape Painter.

The term “landscape” actually derives from the Dutch word “landschap”, which originally meant “region, tract of land” but acquired the artistic connotation, “a picture depicting scenery on land” in the early 1500s (American Heritage Dictionary, 2000). Interesting this is also a similar word in my mother tongue, Afrikaans, Landskap. It seems that initially artists looked at landscape paintings by earlier masters such as Claude Lorrain or Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665), who created idealised landscapes in which mythical figures or classical ornamentation gives an historical or classical impression to the image. With such so-called ‘historical landscapes’, landscape painters attempted to justify themselves in the superior genre of history painting by letting the landscape play the most prominent role in the depiction of a historical subject. The artistic shift to Landscape paintings/drawings seems to have corresponded to a growing interest in the natural world sparked by the Renaissance. By the time the Romantic thought arose, landscape artists turned more and more to the countryside. Artists therefore focused increasingly on the depiction of the natural scenery around them and the emotions that nature evoked in them, rather than imitating earlier artists by focusing on idealised landscapes or merely presenting an exact copy of nature. The romantic landscape painters added an inner expression of the landscape.

It is my view that artists of landscape have the ability to almost condition a viewer about a certain view or way of looking at the world.

Albrecht Durer (1471 – 1528)

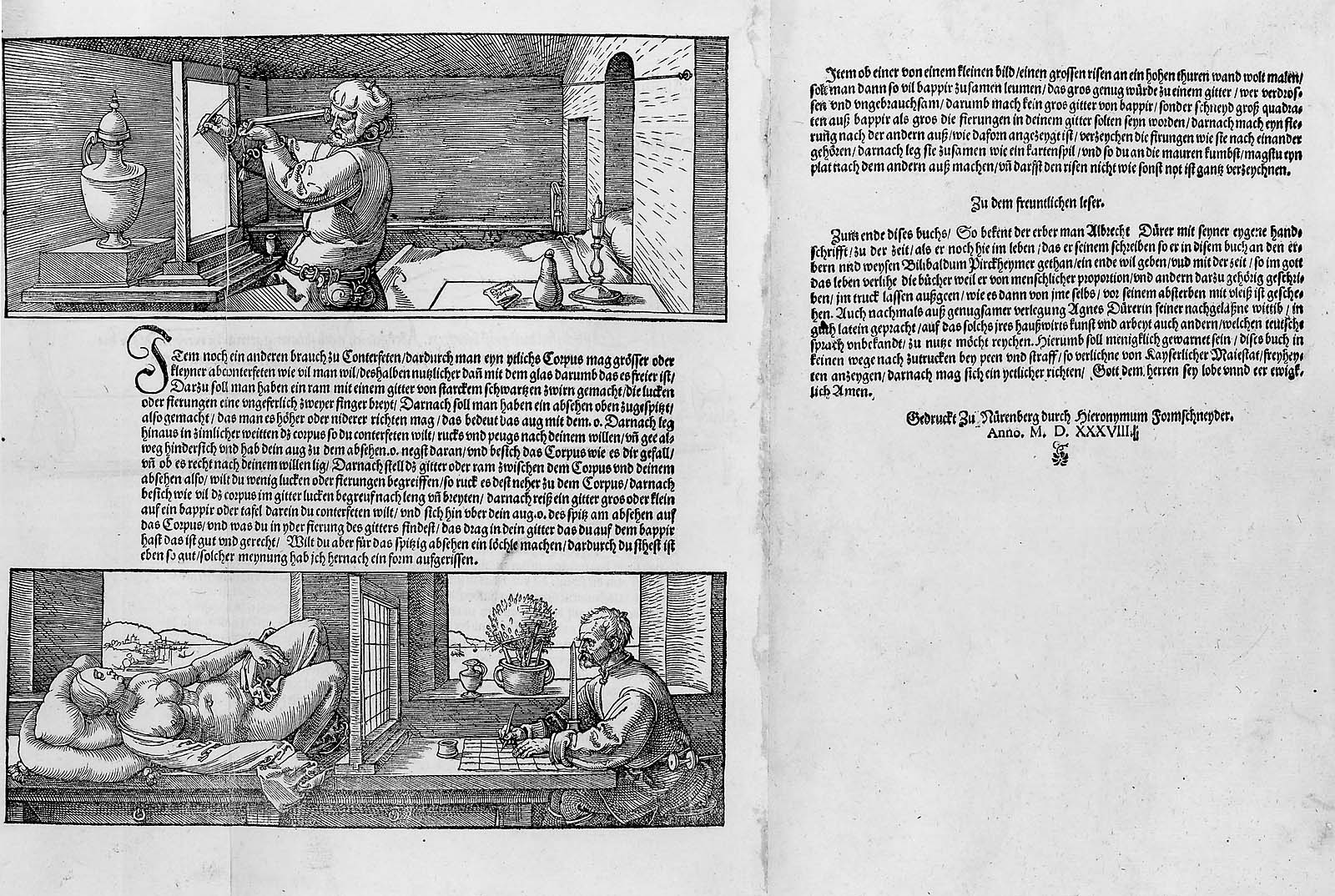

In 1525 the artist Albrecht Dürer published a treatise on measurement which included a series of illustrations of drawing frames and perspective machines. The aim of these devices was to enable artists to take accurate measurements of their chosen subject or to trace a scene as it appeared before them in order to create a convincing illusion of the real world.

It seems his landscape paintings in mostly watercolour and guache was done earlier in his life. Durer shows interest in the world around him, but also manages to use his knowledge of perspective he learnt from his travels and studies in Italy.

According to my research, Durer’s watercolors can be divided into two groups. The early examples frequently include topographical studies which are the first autonomous coloured landscapes to record particular locations in detail. They still contain some perspectival uncertainties, such as the depiction of the Wire-drawing Mill. Here, the artistic interest in producing a realistic picture is at the fore. This reminds me of the ideas discussed in my notes on Landscape. It seems he is using forms of the roofs to create an interesting composition of this particular landscape. It does not seem that he wanted to capture a mood or emotion with this landscape, other than a permanent impression of the view over the roofs.

The detailed record is now subordinate to the harmonious effect of the whole. A single motif that aroused Durer’s interest, such as a section of wall, a mass of roots in a quarry or a complex of buildings, may stand out from the otherwise summary picture, captured with a few brushstrokes and colour surfaces. In his later work, the Quarry, dating from about 1506, a section is placed freely on the surface of the picture. Here, Durer is experimenting with the technical opportunities of watercolour by allowing various brown tones to come into effect in numerous nuances and shades.

The knowledge of perspective gained in Italy was already leaving its mark on watercolors such as the Landscape near Segonzano in the Cembra Valley. His knowledge about the influence of light and air on the appearance of colour only becomes noticeable in later works. These move from a natural to an atmospheric and cosmic record of landscape, which becomes clear both in the overall composition and in the more relaxed use of colour.

Claude Lorrain (1600 – 1682)

Lorrain ( Gellee) was a French artist who spent most of his time in Rome, Italy. It seems that is work is very much in line with his contemporary Italian artist. His work is seen as poetically and the scenes are described as “Arcadian”. According to Wikipedia, Arcadia (Greek: Ἀρκαδία) refers to a vision of pastoralism and harmony with nature. Apparently the Roman poet Virgil had described Arcadia as the home of pastoral simplicity.

Above: Landscape with Cephalus and Procris reunited by Diana1645, it is done after the story from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’ (Book VII) where Diana, goddess of hunting, gave the huntsman Cephalus a magic dog and spear. Ovid’s story ends tragically with Cephalus accidentally killing Procris with the spear. The happy ending shown in this painting by Claude is unusual. I like the silhouettes he creates with the trees behind the animals. I read the following interesting facts about the artist: Claude was never able to draw the human form successfully. His biographers and contemporaries testify to this. The figures in his landscapes were usually painted by assistants or collaborators such as Jean Miel, Filippo Lauri, Jacques Courtois, and Francesco Allegrini. In some cases, however, he painted them himself.

I read: “Claude’s work of the years 1645-1648 shows a considerable advance over that of the earlier periods. A comparison of the Mill in the Doria collection, painted in 1648 or slightly before,with an earlier picture such as the Village Feast in the Louvre, painted in 1639, is an excellent example of this.”

I love how he used trees to create a frame. The sky and the clouds in this work is also beautiful. According to National Gallery his use of trees is giving the composition an overall balance. In his work it seems the artist is a competent ‘drawer’ of landscape, with emphasise on his use of light and silhouettes – almost to picture-like for my taste, although not so theatrical. It is also important that this skill in his painting comes with practice and working outside a lot. It seems that he spent most of his painting on landscapes in Rome, Italy and was very much influenced by Northern Mannerism. This is the form of Mannerism found in the visual arts north of the Alps in the 16th and early 17th centuries. Styles largely derived from Italian Mannerism were found in the Netherlands and elsewhere from around the mid-century, especially Mannerist ornament in architecture.

Above painting was an interesting find! It seems the artist Hendrik F Van Lint, painted large landscapes inspired by and sometimes even copied after works of Claude Lorrain and produced them to collectors. Like Le Lorrain, Van Lint devoted special attention to the trees which grow in Rome and the surrounding region. His wide open compositions are imbued with silence and invite contemplation. Hendrik received the nickname “Studio” which demonstrated the care with which he prepared his compositions. In his signature he subsequently added this nickname to his name. His nomination in 1744 as academician of the artistic congregation of the Virtuosi del Pantheon, and later rise to the title of “Prince” in 1752 attest to his moral and artistic reputation in Rome. It was in the Eternal City that he died at the age of seventy-nine, on September 24, 1763, in his house on the Via del Babuino.

Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840)

Dismissing the picturesque traditions of landscape painting, Friedrich embraced the Romantic notion of the sublime. Through his sensitive depictions of mist, fog, darkness, and light, the artist conveyed the infinite power and timelessness of the natural realm; the viewer is physically reminded of his frailty and insignificance. His painting, The Wanderer above the sea of fog (1818) seen as key work from the Romantic period, this piece conveys the awe-inspiring and sublime characteristics of nature. Through the thick fog, jagged cliffs in the background and rocky mountains topped with trees emerge in the distance. While a figure is featured in the center of the canvas, his back is to the viewer, redirecting his gaze to the backdrop.

As the man contemplates the vastness before him, the sublimity of nature is demonstrated not in a calm, serene view, but in the sheer power of what natural forces can accomplish. The viewer is touched by the subtle colour palette.

Joseph M W Turner (1775 – 1851)

This British artist was seen as a Romantic Landscape painter. Although Turner was considered a controversial figure in his day, he is now regarded as the artist who elevated landscape painting to an eminence rivalling history painting. Although renowned for his oils, Turner is also one of the greatest masters of British watercolour landscape painting. He is commonly known as “the painter of light”.

One of his most famous oil paintings is The Fighting Temeraire painted in 1838, which hangs in the National Gallery, London. The artist was already in his sixties when he painted ‘The Fighting Temeraire’. It shows his mastery of painting techniques to suggest sea and sky. The paint is laid on thickly and used to render the sun’s yellow rays striking the clouds. The sky is absolutely beautiful, and the colour of the sea, which influenced by light, is just great. By contrast, the ship’s rigging is meticulously painted.

Turner travelled widely in Europe, starting with France and Switzerland in 1802 and studying in the Louvre in Paris in the same year. He also made many visits to Venice. He used sketches in his sketchbooks to make notes, drawings and detailed info during his travels. One popular story about Turner, though it likely has little basis in reality, states that he even had himself “tied to the mast of a ship in order to experience the drama” of the elements during a storm at sea. If this was indeed said by Turner, I agree that “this statement reminds us rather of a modern and avant-garde artist of a much later time, indifferent about others’ opinions and engaged with expressing his own impressions and inner experiences upon a work of art.” (taken from a RMA thesis: This made me a Painter, Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context, Utrecht University)

Marine paintings was an important part of his oeuvre. It is just so lovely for me, not being able to visit the National Museum, to be able to watch short video clips done masterly by the curators – the one on Turners’, Fighting Temraire being tugged to her last berth, was just so great!

Vincent van Gogh

I felt I had to visit Van Gogh’s drawings of landscape for this research, and a great video of the Van Gogh museum encouraged this part of my learning. From the very beginning, he was painting the Dutch landscape around him. In 1882, Van Gogh was painting the sea, dunes, and woods of the Netherlands in dark, muted earth tones. In these early Van Gogh landscapes, he was still developing as an artist and was not yet painting in the style that he would be most known for. He wrote to his brother, Theo, “I’m certainly no landscape painter, if I were to make landscapes there would always be something of the figure about them.” One of the themes in Van Gogh’s paintings from Asnières was the rise of industrialism and its influence on the rural landscape. For Van Gogh, peasant life and that of the agricultural worker were seen as, perhaps, the truest form of living. His beautiful and famous Starry Night paintings come to mind – as it is of a city scape at night.

During his visit to Arles in 1888, Van Gogh discovered the reed pen (made from local hollow-barreled grass, sharpened with a penknife). It changed his drawing style. He created some extraordinary drawings of the Provençal landscape, including a series of drawings of and from Montmajour (east of Arles) , in reed pen and aniline ink on laid paper. The ink has now faded to a dull brown. My reason for looking at his works, are also because of his fascination with trees – I read in his letters to his brother Theo that he thought trees had ‘souls” In the video of Van Gogh Museum there is reference to his study of Japanese prints. “Van Gogh was much impressed and influenced by ukiyo-e prints – depictions of everyday life in Japan which were usually done as woodcuts and were of a fairly small size. He collected ukiyo-e prints and this collection now resides in the Van Gogh Museum. He learned about: the use of bright colours; their characteristic compositions, daring perspectives and tiny figures populating the scene. The Japanese prints set the tone for drawings done in the summer of 1887 and subsequently. In April 1888, he announces to his brother Theo that he wants to make drawings in the manner of japanese prints and would have to do a tremendous amount of drawing.”

Claude Monet ((1840 – 1926)

Monet was a founder of French impressionist painting, and the most consistent and prolific practitioner of the movement’s philosophy of expressing one’s perceptions before nature, especially as applied to plein-air landscape painting.

Monet was fond of painting controlled nature: his own gardens in Giverny, with its water lilies, pond, and bridge. He also painted up and down the banks of the Seine. Between 1883 and 1908, Monet traveled to the Mediterranean, where he painted landmarks, landscapes, and seascapes, such as Bordighera. He painted an important series of paintings in Venice, Italy, and in London he painted two important series — views of Parliament and views of Charing Cross Bridge.

Wassily Kadinsky (1866 – 1949)

A Russian born abstract artist. His “Winter Landscape” is one of the works in which the individualities of the artist, being the founder of abstract art, are shown in the full extent. The motive of thin black trunks is often used by Kandinsky in his landscapes.

Bright colours, with dominant pink, yellow, blue and black is based on immediate visual impressions: the author seeks to convey various light effects in the snow lit by the setting sun; and the spatial depth of the landscape is emphasised with the composition.

Above is of his earlier work, which reveal Kandinsky’s strong interest in the tradition of capturing light and the life of cities evident in Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, as well as his love of vibrant and expressive colour. This work was done during his regular travels to Germany and the Netherlands. It represent his impressions of other cities and landscapes that he visited.

Henry Matisse ( 1869 – 1954)

The Landscapes of Matisse represents the moment at which Matisse began to use a more instinctive, spontaneous way of painting that was unparalleled among his contemporaries. The landscapes he painted in the summer of 1905 were “wilder, more reckless than any subsequently produced in his career,” according to Matisse scholar John Elderfield. “In the works of that period colour speaks for itself with a directness previously unknown in Western painting, and speaks directly too of the emotional response to the natural world that required changing the colour of this world the better to render that emotion. In the Landscape of Collioure, he worked directly with his colours on the canvas.

A view from the interior of an automobile! I do love this view of a landscape. It reminds me of videos I have taken whilst driving to my home, on the road I pass thick pine trees on both sides of the road, as well as videos of the landscape of the dry Northern Cape where trees are so scarce amongst the rocky outcrops. In normally call these videos ” virtual reality, as the 4×4 vehicle bumps along the roads, and my video footage is not the best quality due to these bumps in the road.

Jacobus H Pierneef ( 1886 – 1957)

This South African artist was born from Dutch parents and with the war of 1900 between the Boers and the English, the Pierneef family decided to move back to the Netherlands in 1901. Hendrik continued his schooling in the Netherlands. This experience brought him into contact with the works of the old masters and it had a lasting impression on him. He studied part time at the Rotterdamse Kunsakademie. He was one of the most prominent South African artists whose modernist and geometric style revolutionised South African art in the early 20th century. What I find interesting is the Eucalyptus trees he painted as well as did printing – as we find this in many farming areas of the country.

L S Lowry (1887 – 1976)

His initial drawings were made outdoors, Plein Air, often rough sketches on the back of an envelope or whatever scrap of paper was to hand. More finished drawings were made later and, after about 1910, he only ever painted at home in what he referred to as his workroom, rather than his studio. His palette was very restricted and he used only five colours – flake white, ivory black, vermilion (red), Prussian blue and yellow ochre. Lowry had also painted empty landscapes and seascapes for many years and in the 1960’s he made repeated visits to the north east of England, particularly Sunderland. Many of his seascapes from this time are based on the view from his room at the Seaburn Hotel where he was a regular visitor.

I found the following as part of a letter sent to Tate:”When I started it on the plain canvas I hadn’t the slightest idea as to what sort of Industrial Scene would result. But by making a start by putting say a Church or Chimney near the middle of the picture it seemed to come bit by bit.”

George Shaw ( 1966 – )

He is a former Turner Prize-nominee and renowned for his highly detailed approach and suburban subject matter, and for his idiosyncratic medium – Humbrol enamel paint, typically used to colour model trains and aeroplanes. His preferred medium, Humbrol enamel paint, is a deliberate means of distancing himself from the traditions of oil painting. He also never uses people in his paintings.

Shaw is known for his luminously atmospheric depictions of the urban landscape and woodlands of central England. Painting scenes from his native region, Shaw meditates on the central themes of relationships, ancestry and love. I found it interesting to read that he grew up with L S Lowry’s prints in his home. He says: “His pictures were not the world I knew. I’m not too sure it was the world my dad knew – even though he was brought up in the north west during and after the war. Like the films of the ‘kitchen sink’ sixties, these images of working class life parked themselves in my eighties adolescence; not as documentation but as visionary mythology. Lowry soaked up the world and squeezed it out in the shape of his own imagination. ”

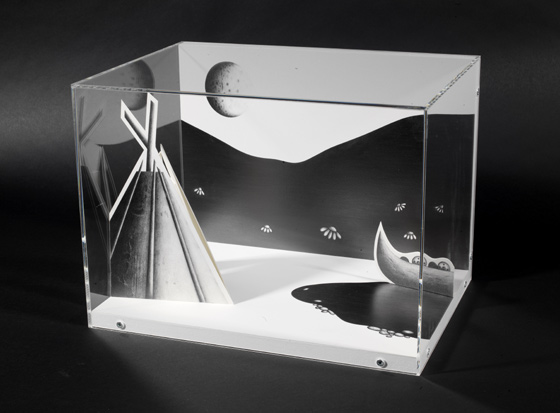

Sarah Woodfine

Sarah Woodfine trained as a sculptor. Her drawings are often constructed as self-contained three-dimensional worlds reminiscent of architectural models and of children’s toys such as cut-out card castles and toy theatres. It is interesting to read that she won the prestigious Jerwood Drawing Prize in 2004. Her work is therefor vital evidence of the emergence of drawing as an independent art form and not merely a stage in developing work for other media.

Here each element is drawn with pencil.

Jeanette Barnes (1961- )

I saw her work on OCA website ( In conversation) I love her loose work style.

She works mainly with willow charcoal or conte crayon in large scale. She mostly tries to work on location. “In the studio I put all my sketches around me and will make one or two compositional drawings from these. I staple a large piece of paper from a roll on to the wall, tie a piece of compressed charcoal on to a stick, so I can work on the drawing at a distance and begin trying to fit the diverse bits of information together, seeing what works and what I need to change. With this method I can’t be too detailed early on, when I have a reasonable composition, I draw with the compressed charcoal in my hand. The work isn’t about capturing one moment in time, but more trying to piece together a history of events. The large drawings can go on for months.” Her large-scale works depict the bustle of the streets and traffic, the movement of cranes sweeping across the sky and the mystifying process of buildings being assembled. I watched a short time lapse video of her sketching and photographing areas around London, capturing the energy and the speed of the city. I also found a longer video is on Vimeo. Interesting to hear her say that she like to see herself inside her drawings – looking through or for things or information.

Heather and Ivan Morison .

I included this collaboration pair due to my own interest in ecology, anthropology, living sustainability and connected and how an artist can become part of solutions by interacting with civil society. I understand their work is mostly commissions for public spaces all over the world and that they take time to ‘get the feeling’ of a place or situation. (great story about their involvement with a special needs school who had difficulty with resistance to change of the locality of their school building) I particularly like the two statements below, a feeling and embodiment of place .

This is part of their artist statement: “I am so sorry” ( I will make art..) and “Artists know the way to solve a problem is to begin.” (the idea that an artist is not so risk averse)

“Artists now work in a vastly expanded field, transcending traditional divisions within the creative arts, acting in collaboration with many other areas of creativity, thought and commerce, often directly addressing major societal questions of our time.

We are living in a period of great change in which opportunity and dignity are being stripped away from individuals and communities.

It is essential that we seize control of the forces of change to shape them into the future we want.”

Lauren Halsey (1987 –

This artist builds her own platforms for engagement that promote creative space-making in gentrifying neighbourhoods. In “we still here, there,” Halsey’s solo exhibition at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art’s Grand Avenue the artist presented installations that include fake plants, rugs, shattered compact discs that form stages for black figurines, as well as sphinxes and other statuettes based on Egyptian iconography. A grotto is the set where every things plays out.

I looked at her large -scale public art installation called, The Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project as planned for the neighbourhood and a current work in process. It is I understand that artist is seen as a Visual artist – but she is using her landscape to create conversations and connecting with her target audience.

Reflection:

What I take away from the contemporary Landscape artists is how they open themselves up during the process of creating their work – making them so very creative and in touch with modern life and the landscape thereof.

The landscape around me can sometimes be so deceptive – all pastoral ( we live on an estate which is part of a dairy farm: one of the last in the city, with lovely park areas for walking and recreation as well as a beautiful golf course), yet a polluted river that runs through is in a terrible state, and the surrounding area are influenced by the dangers of crime, corruption. loss of purpose and poverty (people living in shanty towns down the road, beautiful old buildings and even art galleries lacking maintenance and general up keeping)

In the book, Vitamin D, in the paragraf , All the world’s a drawing, there is reference made to Land Art as inescapably drawing. The image of Richard Long’s “A line made by Walking “( 1967) I see how an artist can act on landscape by making a ‘mark’ on it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

http://www.moodbook.com/history/renaissance/durer-life-and-work.html ( accessed on 7 June 2018)

http://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/17/to-the-ends-of-the-earth-art-and-environment ( accessed on 7 June 2018)

PDF : A Landscape by Claude Lorraine https://www.metmuseum.org/pubs/bulletins/1/pdf/3257307.pdf.bannered.pdf (downloaded on 7 June 2018)

National Gallery

Vitamin D, New Perspectives in Drawing, Phaidon Press Limited, 2005,

William Turner.org

RMA Thesis https://dspace.library.uu.nl/…/RMA%20Thesis%20-%20Final%20Version.pdf?…2…by M Mohr – 2014 –

TATE blog dated 26 September 2013, Artist George Shaw: Lowry’s pictures weren’t the world I knew.