Potts states that words and pictures/images are signs, activated by “cultural convention” (2003,20). and a work of art operates like a sign. The viewer ‘who assign significance to a world of visual art is like the user of a language who envisages a word or a text as having meaning because she or he has internalized the rules of the language concerned. Semiotics is a philosophical theory of signs. According to Saussure a sign is the basic unit of meaning and they are made up of two parts, the Signifier and the Signified. The Signifier is the form of a sign (could be a sound, a word, an image such as a photograph, a painting or a facial expression). The Signified is the concept or object that is represented (it could be an object, a command to stop, a warning). Pierce added a third to this semiotics of signs, namely the Interpretant, what the audience make of the signs. In this way we turn to the ‘realist understanding of how signs operate (2003,20) Pierce explained that we only think in signs and added that anything is a sign if someone interprets it as meaning something other than itself. So the idea is to focus attention on the reference a sign makes to an object other than itself. He also added that signs can be defined as belonging to one of three categories, namely the icon, index, or symbol. Pierce’s semiotic theory is relevant for the study of art as it makes us think about art in history, in society, that is not bound up with the intention of the artists. Mieke and Bryson (1991, 191) says it can “contribute to the explanation of why certain elements of an image are particularly seductive or deceptive, suggesting depiction of something real, while specularity, a return to the self away from the real, is in fact the basis of the seductiveness.” Potts says that ” a theory of the sign, as a distinct form a theory of the image or a theory of representations, gives a distinctive cast to the analysis of a work of art by focusing on its function as a vehicle to convey meaning.” (2003, 21)

Another point to keep in mind is that the correlation between signifier and signified in an index can be known innate or learned. A smile/laughter is an index of being happy and it’s something we all know innately. On the other hand a red stop light is an index for stop, but it’s something that we all needed to learn. De Saussure said signs aren’t meaningful in isolation: a thing and its name have a totally arbitrary relationship. It challenges the idea that language and reality have an organic relationship, meaning that that names rose out of the thing. Meaning comes from interpreting signs in relation to each other; it is almost as if we know things by accessing their shadows through language. Signs communicate by:

- resembling what they represent, or

- by implying what they represent, or

- through arbitrary representations that must be learned before we can understand their meaning.

Semiotic approaches claim that meaning and truth are not inherent properties of things but are socially constructed. Baudrillard claimed that the mass simulacrum of signs become meaningless, functioning as hollow indicators that self-replicate in endless reproduction. Baudrillard claimed that the Saussurean model is made arbitrary by the advent of hyperreality wherein the two poles of the signified and signifier implode in upon each other destroying meaning, causing all signs to be unhinged and point back to a non-existing reality. Derrida’s theory of signs runs counter to the Saussurean model as well. He elaborated a theory of deconstruction that challenges the idea of a frozen structure and maintains there is no structure or centre, no univocal meaning – we have infinite shifts in meaning relayed form on signifier to another. For Derrida the schema in which the direct relationship functioned has been rethought. Summers (2003,13) states that representations are “primarily significant not only in terms of what is represented, but also in terms of how it is represented.” he sees the what of representations as the subject matter, and says it is most significant for what it reveals in having been chosen, and the how, the manner of treatment, reveals the syntheses and schemata. In looking at this view he concludes that a work of art can express both a personal and collective points of view. If I look and think about above ideas, it is important to notice the history of presentation within an imaginative formation and then Baudrillard who ceaselessly reminded us of the domination of the image and of cultural life that is reduced to the hyperreal. One of many methods for understanding an image, structuralist semiotics maintains that language and cultural products are systems of constructed signs; everything has sign value and meaning can be found in the underlying structure inherent in cultural products. For texts, meaning may be brought about by reading objects as signs and relating these signifiers to signifieds. As a predominantly linguistic model of analysis, it may be difficult to translate paintings into sets of semiotic signs, signifiers and signifieds. A sign is being treated by the user as representing or ‘standing for’ other things. Structuralism is not an ideal analytical system to apply to every aspect of a painting because defining what a sign in a painting is may not always be possible. Furthermore, post-structuralists maintain that language and signs, and thus their meanings, are culturally conditioned, subject to biases and therefore cannot be fixed, reliable and objective meaning givers. Meaning then cannot just come from observing only an object, but from ‘deconstructing’ it by looking at the systems of knowledge and contexts used to produce it. This implicates that our language of words do not necessarily name only physical things which exist in an objective material world but may also label imaginary things and also concepts.

“A photograph is both a pseudo-presence and a token of absence. Like a wood fire in a room, photographs—especially those of people, of distant landscapes and faraway cities, of the vanished past—are incitements to reverie. The sense of the unattainable that can be evoked by photographs feeds directly into the erotic feelings of those for whom desirability is enhanced by distance.” (1979, 16) Photos reminds us of the absence of that which is represented.

Sontag Susan, 1979, On Photography. Kindle Edition

Potts Alex, 2003, Sign, Critical Terms for Art History, Second edition, Nelson Robert S & Shiff Richard. Kindle edition

Bal Mieke, and Norman Bryson, 1991, “Semiotics and Art History.” The Art Bulletin, vol. 73, no. 2, 1991, pp. 174–208. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3045790.

Nature / culture

- The realist acknowledges the separate existence of natural phenomena.

- The constructivist treats everything as included under culture.

My first thoughts on nature is the idea I have that what comes from nature is a gift, it is not man made, and then… man, as everything else, developed by ‘fits and starts’, to use Deleuze’s reference to a starting point. Nature and natural signs (a leopards footprint), which is observed by us as signs of life is an abstract concept, we do not necessary understand the intention of the sign, where as with cultural signs which we have created through intention and function, mainly through language interpretation, we can make meaning of it. Sign implies a causal connection or resemblance – in nature we can also observe this. I almost immediately thought about the ‘observer effect’ which I read about in a BBC article on a possible link between quantum physics and the human mind. (Ball, 2017) The discussion is whether objectivity was an illusion, or as Albert Einstein complained, the ‘Moon does not exist only when we look at it” The fact is, we as observers bring interest to signs, if they are caused naturally or if they were the effects of our own intention. What quantum physics actually might be showing us is the notion of scientific determinism which governs the micro world of atoms and particles. According to quantum mechanics, you cannot predict with certainty what route a particle will take to reach a target – even if you know all its initial conditions. All you can do is to calculate a probability, which implies that nature is a lot less predictable than we thought. In fact, it is only when you actually measure a particle’s path that it “picks” a specific trajectory – until then it can take several routes at once. These quantum effects tend to disappear on the scale of people and everyday objects, but it has recently been shown that they may play a role in some biological processes, ranging from photosynthesis to bird navigation. So far we have no evidence that they play any role in the human brain – but, of course, that’s not to say they don’t.

Leonardo looked for resemblance in the stains on the cave. The way we explain consciousness depends on how we see the world. I am also reminded of a path from ‘myth to reason’, which I think is a continuing and collective discovery of a symbiotic evolution of nature and culture, even before the philosophers started searching for wisdom. I take note that the philosophers of the day call consciousness, ‘the hard problem’ and J Searle’s arguments against the ‘mind/body’ problem. It seems David Chalmers had opened up these discussions and that there is at least some consensus is the way we accept that the mind could affect outcomes of measurement. When this “observer effect” was first noticed by the early pioneers of quantum theory, they were deeply troubled. It seemed to undermine the basic assumption behind all science: that there is an objective world out there, irrespective of us. If the way the world behaves depends on how – or if – we look at it, what can “reality” really mean? The most famous intrusion of the mind into quantum mechanics comes in the “double-slit experiment”. Some of those researchers felt forced to conclude that objectivity was an illusion, and that consciousness has to be allowed an active role in quantum theory.Whether we think of ourselves as biological or social, cultural, intellectual, materialistic or spiritual beings, or we identify with all of these definitions, each of us is free to determine what we value.

Nature presents itself as a reality which is characterized by permanence and stability: the recurrence of seasons, day and night, the constancy of living forms and of the material world. This cause nature to be seen as a kind of guarantee of the substantiality of being: the fact that things have a nature gives them a sort of solidity on which humanity can rely in its actions. We know from physicist theories such as the Big Bang Theory that once a physical system is set in motion it follows a completely predictable path – almost as encoded into the initial conditions of being – predetermined. Again, when looking at nature from a quantum physics position and calculating probability, nature seems a lot less predictable than what was thought. I do like this curveball as duality comes into play – I would like to think about my brain as part of my consciousness – as one. Plato said the soul was not dependent on the physical body; he believed in metempsychosis, the migration of the soul to a new physical body. Reading about the Stoics and the Epicureans shows that they believed that all ordinary things, human souls included, are corporeal and governed by natural laws or principles. Stoics believed that all human choice and behavior was causally determined, but held that this was compatible with our actions being ‘up to us’. Chrysippus ably defended this position by contending that your actions are ‘up to you’ when they come about ‘through you’—when the determining factors of your action are not external circumstances compelling you to act as you do but are instead your own choices grounded in your perception of the options before you. Hence, for moral responsibility, the issue is not whether one’s choices are determined (they are) but in what manner they are determined. Epicurus and his followers had a more mechanistic conception of bodily action than the Stoics. They held that all things (human soul included) are constituted by atoms, whose law-governed behavior fixes the behavior of everything made of such atoms. But they rejected determinism by supposing that atoms, though law-governed, are susceptible to slight ‘swerves’ or departures from the usual paths. Epicurus has often been understood as seeking to ground the freedom of human willings in such indeterministic swerves, but this is a matter of controversy. If this understanding of his aim is correct, how he thought that this scheme might work in detail is not known. By now one observe that in many of these disputes about the nature of free will there is also an underlying dispute about the nature of moral responsibility. On the Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy website I read the following: “It is possible that indeterminacy on the small-scale, supposing it to be genuine, ‘cancels out’ at the macroscopic scale of birds and buildings and people, so that behavior at this scale is virtually deterministic. But this idea, once common, is now being challenged empirically, even at the level of basic biology. Furthermore, the social, biological, and medical sciences, too, are rife with merely statistical generalizations. Plainly, the jury is out on all these inter-theoretic questions. But that is just a way to say that current science does not decisively support the idea that everything we do is pre-determined by the past, and ultimately by the distant past, wholly out of our control.”

Art became involved in reaction to cultural issues such as gender in the early sixties and I thought about a recent contentious issue in the athletic world; a transgender black woman, who holds 2 olympic records, is being challenged by an international athletics institution for having an unfair advantage over women due to having naturally higher than normal testosterone level. In order to compete she is expected to use medication to alter/lower specific hormone levels. It is thought these higher hormone levels give her this ability to excel in athletics, this has not yet been scientifically proven. Here we see a nature culture dichotomous relationship, science, gender and sports politics and ethics are being challenged. Many ‘accidents of nature’ are automatically classified as fair advantages: height, muscle composition, arm span, feet size, international sports however does not classify according to these criteria, it only differentiate by sex.

I read about The 11th Taipei Biennial, ‘Post-Nature: A Museum as an Ecosystem” the Frieze.com Facebook page, currently running. It questions the public role of the museum in raising ecological consciousness. The presentation of the works by science, visual art, documentary and film makers, architecture and activism by NGO’s and activists is foregrounded by recent ecological theory that warns us of the impossibility of thinking about nature and culture as opposites.

An interesting word I learnt: AUTHOCHTHONOUS . Websters explain as follows: Ancient Athenians considered their ancestors the primordial inhabitants of their land, as if sprung from the very soil of the region they inhabited. Their word for any true-born Athenian, “autochthōn,” itself springs from auto-, meaning “self,” and chthōn, meaning “earth.” Nowadays, the English adjective “autochthonous” is often used in somewhat meaty scientific or anthropological writing (as in “several autochthonous cases of fever broke out in the region”)”

John H. Bodley, 1999, Cultural Anthropology: Tribes, States, and the Global System,

3rd ed. 1999. online pdf file.

Standford Encyclopedia for Philosophy: Plato and free will. Online website reading.

Exercise 3.8

What does it mean to say nature is culture? Can there be one without the other? What would it be like?

Schopenhauer says, ” Not merely philosophy but also the fine arts work at bottom towards the solution of the problem of existence. For in every mind which once gives itself up to the purely objective contemplation of the world, a desire had been awakened, however concealed and unconscious, to comprehend the true nature of things, of life, and of existence.” (2010,97)

We humans evaluate and reflect about what is going on on earth, the outer space as well as in our own lives, in our communities, cultures, economies and political areas, which we call collectively our environment. We are measuring, comparing, attaching meaning, classifying, naming from our perspective and interaction within our own ‘environment’ with the natural phenomena in/of Nature. The word nature lies in the Latin natus or gnatus, being produced, related to the Greek, gignomai, ‘to be born’, roots that survive in ‘pregnant’, ‘genesis’ and ‘native’. Nature is whatever has been generated and comes to be, and is not constructed by the human mind – we can even think of it as being before we became aware. In most cultures, throughout history of man I think one can observe behaviour reflecting a fondness, fear, admiration for Nature, or lack of interest and value. Artist who end up choosing to work in Landscape reminds of the artist’s connection with Nature and their expressive need to share their surroundings in representations of shapes, colour, light and space – the world around us can be a constant source of inspiration, to poets, writers, photographers and other visual artists. Susan Sontag reminds of how nature changed (1979, 15)and how photos record what is disappearing, photos store and share information – almost as a reality can be constructed and that it gives multiple meanings. Our consumerist culture also turned the experience of taking a photo into a way of seeing – “today everything exists to end in a photograph” (1979,24) Sontag’s reference to Walt Whitman with regards to how he saw America is profound, he call America “the greatest poem” (1997,27) is he is referring to the role that art and culture play in shaping the desires and will of people? Whitman believed that poetry and democracy derive their power from their ability to create a unified whole out of the divided. Whitman initiated over 150 years ago, a dialogue about democracy, poetry, love, death, and the endless permutations of life that he believed would define America and eventually produce a republic equal to its ideals. The remarkable fact is that most American writers/poets/artists, ( like our R W Emerson) at some point, had a confrontation with Whitman where there was a wrestle with his structuring of poetry, the nation, democracy, and the self: “I am large,” he said, “I contain multitudes” . Here is also a reference to Walker Evans’s break with the heroic mode where the artist uses art to identify with community values such a empathy, concord in discord and oneness in diversity. I just recently read the prelude of a book, Figuring, by Maria Popova (Pantheon, February 2019) online, and the following seems so in touch with this question: ” We spend our lives trying to discern where we end and the rest of the world begins. We snatch our freeze-frame of life from the simultaneity of existence by holding on to illusions of permanence, congruence, and linearity; of static selves and lives that unfold in sensical narratives. All the while, we mistake chance for choice, our labels and models of things for the things themselves, our record for our history. History is not what happened, but what survives the shipwrecks of judgment and chance.”

Summers writes the following when he discusses (2003,12) Representation: ” According to the first principles of idealism, the world is represented by us at the same time that it is manifest to us, and weltanschauung is perhaps best translated as world intuition.” He refers to the pictorial character of these visual metaphors and to idealism as from the Greek word meaning ‘to see’. To me reality is this immediate moment, and a constant reminder through my awareness. The term worldview or as I read in philosophy “weltanschauung” is according to Summers (2003, 14) ” the local commonality of the forms of human imaginations, explaining evident differences among groups in terms of the spirits of peoples, place and times…. ” We express this further in words such as society and social culture. It seems that when Kant defined aesthetic judgement being integral with primary imaginative representation, aesthetic also became important in the historical as well as cultural respects. Summers states that we may refer to the aesthetics of a period as much as we speak of its worldview. So it is a reference to the common concept/sense of reality shared by a particular group of people, usually referred to as a culture, or an ethnic group. According to Jenkins (1993) it also seems that worldview can be an individual as well as a group phenomenon. And he states that expressions of commonality in individual world views make up the cultural worldview of the group. “This is the social culture, the way people relate to one another in daily activities, and how they cooperate together for the good of the group as a whole, called the society. This means that every person has a culture in their head. This is what we call their worldview. Thus there is a bit of difference with each individual. The culture in their head, however, includes the areas allowed to be different and those required to be the same or similar. The rigidness or flexibility of the social culture will be a part of that worldview in each member’s head and part of the general worldview.” It is clear that a person’s relationship with culture is complex as it can at once be very personal (local) and also political (global). No one lives in a vacuum and every cultural reality has localised, and globalized components. Our families form a subculture in itself which exerts certain influence over your views as you grow up. To complicate it even further, as we grow up we share some aspects of culture with other members of the community in the city or town in which you were raised. If I look at my own situation, I came from South Africa to the UAE, Dubai, and my cultural reality is different from the culture I now share – the local language and food is different, the religion and social landscape and is different. In art I see more use of letters/words and geometrical shapes.

Anthropology regularly questions what is natural about us humans and what is cultural about humans. Some of our earliest forms of culture, were the cave wall drawings – I see this as an attempt to tell visual stories about the interaction with the world/environment around us. I am also reminded of the exercise on Emerson, reality and cultural hegemony in our study material, on pages 69-71. Emerson in Culture says, “the preservation of the species was a point of such necessity, that Nature has secured it at all hazards by immensely overloading the passion, at the risk of perpetual crime and disorder. So egotism has its root in the cardinal necessity by which each individual persists to be what he is. He refers to human nature and individualism which has brought about egoists. Critical constructivism challenges the view of reality and accepted world views and values, as it shows that cultural power can be deconstructed if not reconstructed. Based on the understanding that knowledge of the world is an interpretation between people that is crafted in a contextualised space, critical constructivists argue that knowledge is temporally and culturally situated, therefore knowledge and phenomena are socially constructed in a dialogue between culture, institutions, and historical contexts. Critical constructivism maintains that historical, social, cultural, economic, and political contexts construct our perspectives on the world, self, and other. Ontologically critical constructivists seek to understand how socio-historic dynamics influence and shape an object of inquiry, and epistemologically critical constructivists explore how the foundations of knowledge of a given context surround an object of inquiry.

In Anthropology the Nature Culture divide has a history of enquiry and theory. The question became whether these two entities function separate from one another, or if they were in a continuous biotic relationship with each other. Two main principles of ecology are egalitarianism between humans and nonhuman and the belief that nature is characterized by a fundamental harmony or balance. The modern environmental movement in the United States originated in the transcendentalism of Henry David Thoreau and John Muir. In deep ecology, the transcendental spiritual ‘nature’ of Thoreau, meets the scientistic objective nature of ecology. Insofar as this was and is the case, Nature or wilderness plays a spiritual role for the environmental movement that is not easily reconciled with its tendencies toward science. Deleuze talks about nature in his chapter about Lucretius and the Simulacrum (2015, 275-287) and talks about Nature being distributive, not collective, to the extent that the laws of Nature distribute parts which cannot be totalized. “Nature is indeed a sum, but not a whole.” He refers to Physics as Naturalism from the speculative point of view – a theory of the infinite. As I understand Lucretius our culture does not bring unhappiness, but myth within our culture, combined with our troubled feelings of false infinite.

I do think nature can be without culture, as culture is what we brought into being by being social and searching for meaning. The entities and phenomena we

now attribute to nature is a category, a type of conceptual container, that permits us to conceive of a single, discernible thing, we call nature. I prefer to go with Albert Einstein’s opinion, namely that the Moon does not exist only when we look at it, but I also believe that we live in a participatory relationship with nature – we are physically and existentially dependent on the natural world, thus connected and should work on this connection and or separation/disconnect. The fact that we exist makes culture part of nature could also be possible. Nature may be a evolutionary ready-made world, but human values are not found ready-made in it. We make up our values. It is also becoming increasingly apparent that civilisation’s “progress” destroys the environment as well as other more primitive peoples and cultures.

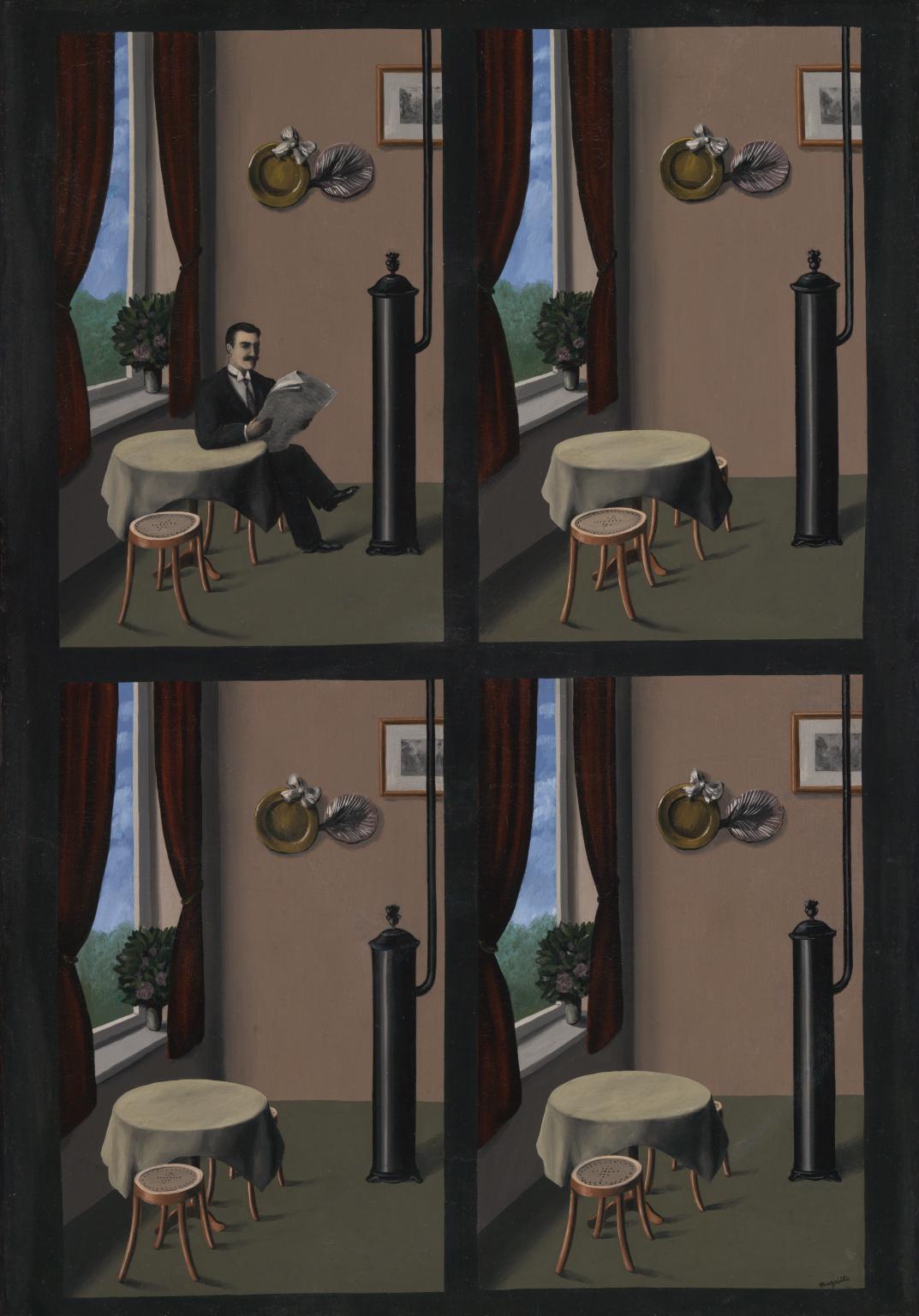

The above painting of Rene Magritte, Man with a Newspaper, reminds one of something existing, without the man being in the room and giving meaning to it whilst reading his newspaper as the name of the painting indicates. I looked at above picture and to me this represents a view of reality – if the man is not there, does he exist?

“The painter’s world is a visible world, nothing but visible: a world almost demented because it is complete when it is yet only partial. Painting awakens and carries to its highest pitch a delirium which is vision itself, for to see is to have at a distance; painting spreads this strange possession to all aspects of Being, which must in some fashion become visible in order to enter the work of art”

Merleau-Ponty “Eye and Mind

What is the term, ‘binary opposition’ – does this apply to nature and culture? Write 3 paragraphs for, against and a conclusion.

The binary opposition is the structuralist idea that acknowledges a human tendency to think in terms of opposition. For Saussure the binary opposition was the “means by which the units of language have value or meaning; each unit is defined against what it is not.” With this categorization, terms and concepts tend to be associated with a positive or negative. For example, Reason/Passion, Man/Woman, Inside/Outside, Presence/Absence, Speech/Writing, etc. Binary opposition is a key concept in structuralism, a theory of sociology, anthropology and linguistics that states that all elements of human culture can only be understood in relation to one another and how they function within a larger system or the overall environment.

Levi-Strauss argued that a universal tendency to draw binary opposites regulates for the way societies construct their structures. Structural linguistic is deeply rooted in binarity of langue/parole. Levi-Strauss began to reduce cultural sign-systems into basic structural unit to establish polar relationship among various units corresponding at different levels. Once, Levi-Strauss established Dualism as the structure of basic human thinking, he posited the question of language of human mind itself. Structuralists argue there is always a question of value attached to these binaries, so they are inherently hierarchical, meaning one of these opposites is always valued more than the other. We often encounter binary oppositions in cultural studies when exploring the relationships between different groups of people, for instance: upper-class and lower-class or disabled and non-disabled. On the surface, these seem like mere identifying labels, but what makes them binary opposites is the notion that they cannot coexist. The problem with a system of binary opposites is that it creates boundaries between groups of people and leads to prejudice and discrimination. One group may fear or consider the opposite group a threat, referred to as the ‘other’. The use of binary opposition in literature is a system that authors use to explore differences between groups of individuals, such as cultural, class or gender differences. Authors may explore the grey area between the two groups and what can result from those perceived differences. In the West, the ontological divide between humans and nonhumans has also meant a hierarchical of valuation of culture over nature, as well as the subjects and objects associated with this divide such as humanity and animality, men and women, civilization and savagery, animate and inanimate along with many other dualisms.(Morrow,13) A very interesting quote is taken from Morrow’s dissertation: “Luther Standing Bear, in Land of the

Spotted Eagle (1933), insightfully commented on the problem of viewing nonhuman

beings as „wild‟ and „wilderness‟: “Only to the white man was nature “wilderness” and

only to him was the land “infested” with wild animals and “savage” people. To us it was

tame” (Standing Bear, 1933: 38)”

Post structuralists tend to reject this idea but they are more about deconstructing binaries and their universality – in particular when it comes to the universality of hierarchies – than outright denying their existence. A great question here to consider is: What sort of world is envisioned without this ontological divide? Derrida rejects binary structure. Derrida argued that these oppositions were arbitrary and inherently unstable. The structures themselves begin to overlap and clash and ultimately these structures of the text dismantle themselves from within the text. In this sense deconstruction is regarded as anti-structuralism. Deconstruction rejects most of the assumptions of structuralism and more vehemently “binary opposition” on the grounds that such oppositions always privilege one term over the other, that is, signified over the signifier. These are opposites – concepts that can’t exist together. Structuralism made it possible to see philosophical systems as all insisting on a center, though a different kind of center; the event Derrida talks about is the moment when it was possible to see for the first time that the center was a construct, rather than something that was simply true or there. That shift, or rupture, was when it became possible to think about “the structurality of structure.” In other words, this is the moment when structuralism pointed out that language was indeed a structure, when it became possible to think (abstractly) about the idea of structure itself, and how every system–whether language, or philosophy itself–had a structure. The assumption that the center ( Philosophical or Belief system – God, rationality) is the basis or origin for all things in the system makes the center irreplaceable and special, and gives the center what Derrida calls “central presence” or “full presence”, i.e. something never defined in relation to other things, by negative value. Post-structuralism in a way throws out ideas of truth, self, and meaning and replaces them with relativism, ambiguity, and multiplicity. Many people would argue that this is what is wrong with the world today, and lament if only we could return to the old-fashioned values of humanism, believe in absolute truth, fixed meaning, and permanence, everything would be at least better than it is now. Derrida argues that what is complete in itself cannot be added to, and so a supplement can only occur where there is an originary lack. In any binary set of terms, the second can be argued to exist in order to fill in an originary lack in the first.

Searle presents three criteria (observer-dependence, the role of forces, and the status of laws) that can distinguish science from the humanities. Searle talks about are criteria which are supposed to define natural science and distinguish it from social sciences and the humanities. His criterion of distinction for one is rooted in observer-dependence: matter is what it is, everything else depends on the mind. An increasing number of phenomena in biology and physics no longer are reduced to forces but are treated like semiotic relations. Life, historically a subject of the humanities, today is an accepted topic of natural science. What prevents humans doing the same with language? – Could be done by using methods drawn from both science and the humanities. There could be no reason why both linguistics and genetics cannot be made a subject of scientific methodology. What if linguistic capacities are find to be neither social nor genetic but something else, not even philosophy but, for example, software code is also being considered.

Holmes Rolston 1997 Nature for real: Is nature a social construct? Hilary Putnam (Reason, Truth and History, Cambridge University Press 1981 p 54) as quoted by Holmes.

Jenkins O B, 1993 “What is Culture?” series in Focus on Communication Effectiveness, a cross-cultural communication newsletter, Nairobi, Kenya, Posted online in June 2001.

Morrow, Johannes, Dissolving Nature and Culture:Indigenous Perspectivism in Political Ecology, PhD thesis published on Academia.edu

Summers, David, 2003, Representation in Nelson and Shiff eds., Critical Terms for art History, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Kindle Edition.

Folsom Ed and Price, Kenneth M , Re-Scripting Walt Whitman: An Introduction to His Life and Work Whitman Archive website, accessed online on 20 February 2019.

Reflecting on this exercise

In many ways we live and believe that everything we say could be said, and that the images we see, could be seen. I understand that Foucault felt strong about the ‘felt experience’ – aisthesis in Greek, even when confronting the intolerable.

Contemporaneity: Historical Presence in Visual Culture aims to explore how the complexities of being in time find visual form. Crucial to this undertaking is accounting for how, from prehistory to the present, cultures around the world conceive of and construct their present and the concept of presentness visually. Through scholarly writings from a number of academic disciplines in the humanities, together with contributions from artists and filmmakers, Contemporaneity maps the diverse ways in which cultures use visual means to record, define, and interrogate their historical context and presence in time.

Exercise 3.9 In what sense is Whiteread’s House indexical and why does this matter for an interpretation of the work?

A sign is anything that creates meaning.

Peirce’s theory of the sign, which include the icon, index and symbol, needs to be used to understand this artists work. The sign stands for something else, and that something is logically absent from the scene in the case of Whiteread’s House, 1993, which is an indexical sign. According to Pierce an INDEX is a sign that denotes its object by virtue of an actual connection involving them. Pierce’s description of the index emphasizes its symmetrical opposition to the icon, the icon’s functions because an object exists. Pierce calls this a real relation in virtue of it being irrespective of interpretation. An index is a sign that shows evidence of the concept or object being represented – it implies the object or concept/idea, like a lion spoor/footprint that of a lion. Here you can see that an index doesn’t resemble the object or concept being represented. The presence of the former implies the latter exists. David Summers ( Summers 5) refers to Aristotle’s treatise on the soul, De Anima, with regards to using sign (semeion) within an analogy of sight, when Aristotle explained it as ” like the impression left by a seal ring in wax” And he continues to say, ” Aristotle understood semeion to mean what we would call an index.”

In Whiteread’s House, 1993, casting is the indexical – the casting implies the existence of a house, it is an imprint of the original object. The cast is not a copy of the original house – the cast is a negative imprint, very much like photography where the negative is the index of the photograph. The outer surface of House points towards the inner surface of the original house, and this immediate connection of existence shows an indexical sign. The imprint also reveals very little of the original print/house. The intent of the artist was to cast a house. I am completely overwhelmed by the idea of ‘absence’ in this work and the emotional power this has! Through the casting the original house became absent, this finished casting represented the absence of the house, and all the houses in this neighbourhood – the whole work was eventually absent, due to it being demolished for the gentrification process, only a memory for those that knew and saw it. It is so very much the same as what happens when life goes on and we only have the history to go by.

I watched a documentary of this work as it was being made in 1993, to understand the significance of it. The House was meant to be temporary after which the redevelopment plans of the area would be continued. The house was a reversed cast made of an empty and condemned, turn of the century, archetypal terraced house in Bow, London’s East End. The specific address was 193 Grove Road in Bow. The artist did not have much choice in the location and did not envisage the ‘political’ attention her work should eventually create. This house was slated for demolition as part of a group of dilapidated dwellings to create green space of the community, the owner was evicted after a years-long fight to keep his home, and was rehoused nearby by the local council. All the other houses have already been demolished and Whiteread was given permission to use the last house before that was also going to be destroyed. To make House, Whiteread used the physical house as a mould, making a cast from the interior by spraying a skin of liquid concrete around a metal armature constructed to support the weight of the work. Coating the whole house took over a month and an additional ten days were needed for the concrete to cure and set. Once solid, scaffolding was erected and Whiteread and her assistants began to remove the exterior brick structure. The final installation was a hardened concrete mold/sculpture of a multi-story house, showing the private details of the interior, not the exterior. The installation only stood for 80 days , when the local government voted to demolish the artwork even earlier than originally agreed. The House made a statement about change through gentrification of an area, but also is an almost unemotional statement of a home becoming just a house, another architectural object. This temporary public sculpture fused everyday forms such as a house with human experiences and memories. It was called unliveable, controversial and unforgettable. The reactions were personal, political and social – it evoked strong feelings from onlookers as well as people living in the community, in the situation of being changed, marginalized and or at the mercy of the council. The site became very much visited and discussed. A council member termed it an ‘excrescence’ , people were angry at the funds being used for this artwork. The artist was awarded the Turner Price in 1993, just after creating House and dialogue was opened up for contemporary art in the UK. During the period that the The House was ‘on view’ it acted as a temporary catalyst to a displaced community, created public debates on urban renewal and the modern ideas on gentrification. It did not change the outcome and actions by stopping or changing that process – only a memory that the House was once a home – somebody did live there once. “I knew of course, while I was making House, it had a political dimension. You can’t make a cast of a house in a poor area of London and not be political.” – Sarah Whiteread

I presumed other than photos taken, videos made and media articles, not very much could be visible that this work even existed. In further reading I found an article on the artist on the website of TATE, dated 6/11/17. I quote the following from this article: “A grid of photographs and a rather dated-looking “making of” documentary are its sole representations in her Tate Britain retrospective. And yet, the work casts a long shadow over her subsequent career. In the UK, it’s far and away her most famous piece—indeed, it’s a key historical work for shaping the discourse around contemporary art in this country—and it served to make the public instantly familiar with her signature technique of creating sculptures by casting the interiors of spaces. Since then, a frequent criticism of Whiteread’s work is that she essentially repeats the same concept over and over, applying it to any number of objects and places. There’s certainly an aspect of monomania to Whiteread’s career…” I wanted to see the area after 25 years and read the following, which I found quite interesting in that the sign that this house left was not just a temporary sign to the collective visual history in this area and even city: The park that was created is named Wennington Green, has two benches which are pointing to the place where House was standing.

In a google earth search on 22 January I could only see a row big trees.

I read the following in Art21 Magazine (online): “Through the indexical trace of architectural elements, each of Whiteread’s casts retain their relation to real conditions and lived experiences in the world, hinting at the diverse and shifting social realities that define domestic spaces.”

She has been nominated for the Whitechapel Gallery’s Art Icon award with Swarovski on 29 January 2019; and 25 years after House, she still works in cast cement, mostly buildings. I

If we overlook the indexical in the interpretation of the work, the meaning behind this work could be misunderstood. The interpretant is in this case also an important part of this work, two people seeing the work can walk away with two different interpretations of what the work is. With regards to indexes it is necessary to ensure that the correlation between the signifier and signified is understood by whoever sees the sign. For example it can be safe to assume that people know smoke indicates fire, in this case that people know artwork, indicates the inside of a demolished house, a memory to something that once was.

This article I downloaded from the internet (romanroadlondon.com) strengthens above point:

“The legacy of Rachel Whiteread’s House

The Houseless Park has now had over 20 years to bed in to the community’s psyche and flourish naturally. In all of the articles and art history books I have trawled to substantiate this article, House’s legacy is written off as a featureless Green with little footfall. As a local, I know this to be a fallacy: children play; peace-seekers read in the sun cocooned by the natural amphitheatre. However, I fear many are unaware of the political battle this site was home to. House is still a succès de scandale in Art History, lumped with the other provocative creations of the YBAs in the early ‘90s – but lest we forget this was our House, E3. There is no blue plaque to House, like there is to the incendiary V-bomb, but next time you are at the Green look for the two simple benches close to the railings on the Grove Road side. As you tread the closely cropped grass, trace the silhouette – our fossil-monument to the East End vernacular.” (Sarah Thacker, 2015)

If I had to just look at this picture of House in my study material my interpretation would have been different, I did not recognize it as a index, a negative cast of a house, only when that information was understood, and I had the contextual information as well, could I understand why it could resonate with feelings of void, loss, memory.

Into this category of Index we can now put the memory of his house, something that once were. I had the opportunity to view and experience her work, The Holocaust Memorial, in Vienna. After reading about The House and her other 3 dimensional work, the work’s ability to expose stories about loss and humanity, how we function, good or bad, within this world is such a breakthrough for modern art – I think to become socially engaged and visible to everyone. Her work reminds me of monuments of the past in my own country of birth – the need to be reminded, be exposed to what happened in our human history and evaluate and value what we learned from each other in order to create better lives. I am also aware of the work’s ability to create a space where the viewer can engage and create his/her own narrative to what is being seen and or experienced when confronted with the work. So many artist of the past have repeated certain concepts over and over – was it because the idea was so vast and diverse, open to more exploration – message/image/phenomena/sublime/sign deemed necessary to convey to others?

I am now at a point where I think I understand from the study material that representation is an amazing part of being a thinking and feeling/sensing being – of trying to come to grips with our existence and reality. We have come a long way in creating universal ways of communicating our thinking and sensing abilities, in order to find meaning and make sense of our reality within visual culture and art.

Higgins, Charlotte: Me, and art icon? Interview with R Whiteread, The Guardian, 25 January 2019, accessed via the internet

Rachel Whiteread: Long Eyes is on view at Luhring Augustine Gallery in New York City until April 30, 2011

Summers David One Representation, in Nelson and Shiff eds., Critical Terms for Art History. University of Chigago Press, Kindle Edition