Topic 3: Community participation

‘In actual practice, how does a group of people become identified as a community in an exhibition program, as a potential partner in a collaborative art project? Who identifies them as such? And who decides what social issue(s) will be addressed or represented by/through them: the artist? the community group? the curator? the sponsoring institution? the funding organization? Does the partner community preexist the art project,

or is it produced by it? What is the nature of the collaborative relationship? If the identity of the community is produced through the making of the artwork, does the artist’s identity also depend on the same process?’

Kwon, 2004:116-117

In this topic, you will examine some of the ethical questions raised by

socially engaged practices. What does community mean, what critical implications do thesepractices have and what is left behind by them?

One model of working with the community is that the artist, curator, sanctioning/funding institution has a clear idea and then finds the ‘community’ that can make their idea happen. In this model, the community can be somewhat incidental. While the identity of the community group is reduced and difference within it unacknowledged, the group is considered different from the dominant culture and the artist/institution. According to Kwon ‘the identity of a community group comes to serve as the thematic content of the artwork, representing this or that social issue in an isolated and reified way. In the process, the community itself can become

reified as well.’ (Kwon, 2004:146)

Exercise 5.8: Community-based models

Find two examples of projects that use different models of working with the community. Describe how they are different in your learning log.

Looking at indigenous cultures and how information is documented I see the difference of approach in work done by Tinh MinHa. She states that in her work she does not wish to speak about, only to speak nearby. In her first essay film, Reassemblage the images were mostly of women (in rural Senegal) at work, and children playing happily. The film is a montage of fleeting images from Senegal and includes very little narration, although it becomes clear that with her work she criticizes the ‘colonial gaze’ and how meaning is assigned upon such images. It starts with an image of children doing things outside and the artist comments that “reality is delicate…..and my reality and imagination are otherwise dull, the habit of imposing a meaning to every single sign.” (Video) Towards the end of the video she says: ‘First create needs, and then help” and then she tells about a peace corps volunteer who sits outside his new house and does not look connected with the place or people, tells he is showing woman to maintain vegetable gardens in order to make an income ( a new intervention from someone outside?) , and comments to her that he is not always successful, she then continues to talk about how women are depicted as the makers of fire and you see people eating around the pots of food women are preparing on fire – a very sociable narrative is playing out, with no comments. I only saw parts of this 40minute film and make my argument around this. If I think of the first part of this course I find so much reflected back in this work of hers – thinking about what mastery really is, something that is found inside as well as controlled by our inner knowing. I share this comment from the E-flux forum: “It is here that Trinh T. Minh-ha delivers a most profound statement: “I do not intend to speak about / Just speak near by”––a total undoing of the privileging of mastery, the form of knowing that requires distance, the one that has possession as its quiet but pervasive aim. “

I use this to link the ideas to community project as seen below and explained by the filmmakers as follows:

Speaking Nearby is a short film that’s part travel narrative, part visual tone poem, and in whole a celebration of the communities we can make.

We have some big questions: How do our vulnerabilities – through physical frailty, aging, or social marginalization – actually make our communities stronger? What are more radical ways we can practice inclusion and reform our community work? How do differences in geography and history subvert our expectations of how people make lives together? The filmmakers looked at connections that develop organically and speak freely, while still seeking insight into how people build communities, care for one another, and accept difference.

I also looked at a community project in Riebeek Valley and think the idea would be to contemplate more and link the learning about how we as humans want to make us the centre of the world and not celebrate and acknowledge our differences as natural part of who we are.

Ilustrations

Bibliography

( https://youtu.be/FSZaRHg0xVs?t)

Exercise 5.9: The Artist as Ethnographer

In your learning log write a summary of the main arguments made by Foster.

Foster cautions that a realistic assumption will have structural effects and warns artists for assuming that this ‘other’ is always outside. Foster looks at ‘alterity’ becoming the primary point of subversion of dominant culture and argues that it has become problematic to situate the ‘other’ in an ‘outside world’, since ‘in our global economy the assumption of a pure outside is almost impossible’. He suggests that postcolonial artists and critics increasingly ‘pushed practice and theory from binary structures of otherness to relational modes of difference, and pleads for the artist as ethnographer to explore, not ignore, these mixed border zones.

I think art is relational in the way that an artist is always working in relation to his/her environment, and as soon as the work is shown, there is a new relationship with the audience and the work and the audience and the artist. There is also this thing around the division between art and life that I am contemplating. As an artist I am thinking a lot about my own selfhood/identity during my work process, but ‘the other’ comes up in so many ways – I feel I cannot escape it , whatever place I find myself in. My own work has so much to do with what I daily experience of place as well as my relationship to place and people around me, which from a personal point I can describe as ‘the other’. What I became more wary of, is how this description can be perceived by the viewer. I think about the artists we have looked at during the course, some work could be viewed as making the other ‘exotic’,, or the practice becoming somewhat ‘hegemonic’. Since we moved to Dubai, I ‘parked’ my rhino project in a way – I did not feel connected to the cause and know I still need more fieldwork to really take the project further. My studies have helped me to come to terms with ways I could deal with this when I move back to South Africa. The most significant was how to not ‘talk down’ or to judge people, and by looking at new materialist ideas to bring into my practice, which is becoming more practice lead. I realized that understanding needs to happen from many levels and sides – but mainly the population living with and around wildlife and how they see ‘consumption’ and living a decent life within that space. I am more aware of having a mind of a ‘master’/colonial’ when looking at how ‘indigenous’ culture operates.

To create work that is relational an artist will be involved in a process of showing the experience of making in a way that there are no barriers between the artwork and the spectator whilst the artist keeps questioning the idea of display and how we value art.; about these interactions with art. I would think if work is more open-ended so that viewers can grapple with questions themselves, the artwork also becomes more relational as it is pulled into everyday life. Objects (art) need to be seen and questioned from a perspective of how we live with and around them over time. It takes me back to where the course started with praxis and poiesis, thinking of practices and processes to get to a work of art, or a body of work, which sometimes has to take you as the maker to that place of research, finding information, listening to others, being open-minded about outcomes of the project and not expect to find all the answers, or being the ‘more knowledgeable about the subject.

I looked at artist, Rirkrit Tiravanija who has since the 1990s, managed to align his artistic production with an ethic of social engagement, often inviting viewers to inhabit and activate his work. The best-known series, begun with pad thai (1990) at the Paula Allen Gallery in New York, where the artist rejected traditional art objects altogether and instead cooked and served food for exhibition visitors. In an interview he talked about a line being crossed – people not just being consuming but also partaking – the second exhibition he was cooking too slow, so people started helping with the making and cooking of the food the viewers could eat for free., but also were socially interacting with other viewers. Here one has people in a gallery, but becoming ‘part’ of artwork and I can imagine starting to ask questions about what is art, is this art? Looking at some of his later works and a project he started in the north of Thailand, I think this work process was starting to ‘blur boundaries’ and looking at how one can live a more ‘authentic’ life, which is not so mediated by politics or consumerism. I feel here is again confirmation of the process of developing your practice over time – expanding and experimenting, not always very structured and planned, (very spontaneous way of working) being open and never be tempted to stagnate and become unaware of your surroundings. One also sees how he uses different materials – cooking, installation, ceramics, paint, social interaction, printmaking drawing…..

Can one look at his work as a practice based art project?

Kwon is clearly not so concerned with the possibilities of accurately representing the ‘other’ and his/her culture, and sees the the ethnographer attempting to comparatively relate his/her own cultural frame to that of the ‘other’, in view of establishing an interactive relation.

Cummins views can take me into further contemplation of this learning:

“If we believe in producing our own conglomerate subjectivities, as theorised by Bourriaud and Guattari; art can provide a platform for testing the limits of available distinctions. Whether ameliorative or antagonistic in intention, a relational artwork is never complete – it ruptures the fabric of convention, and blurs the lines of art, conformity, and social acceptability. As Guattari explains, art can move in one of two ways;

It can move in a direction parallel to uniformitization, or play the role of an operator in the bifurcation of subjectivity…This is the dilemma every artist has to confront: ‘to go with the flow’, as advocated , for example by the Transavantgarde and the apostles of postmodernism, or to work for the renewal of aesthetic practices relayed by other innovative segments of the Socius, at the risk of encountering incomprehension and of being isolated by the majority of people.”

Further thoughts and actions:

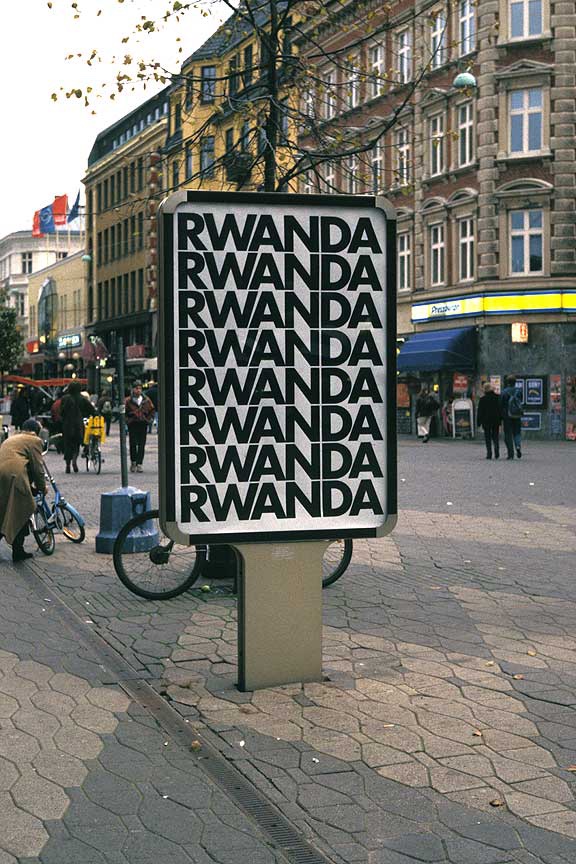

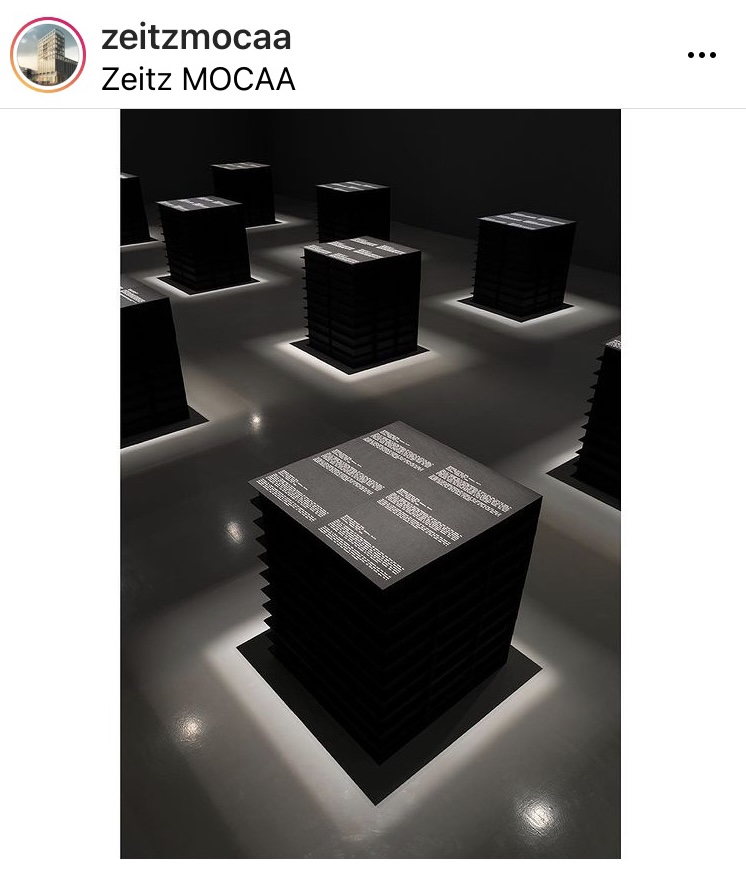

On Thursday evening, 25 February 2021 I was listening to a Zoom talk between Chilean born artist, Alfredo Jaar and Koyo Kouoh, Executive Director of the Zeitz MOCAA gallery in Cape Town, South Africa on his current exhibition on the Rwandan Genocide, done 25 years later and currently shown at the gallery – called The Rwanda Project. His project lasted 6 years. This is a initiative of Galerie LeLong and was the first of a series of conversations that will address topics related to artist’s areas of research, including sociopolitical issues and community engagement.

The artist used photo images, video installation, words, poetry and neon writing to connect the viewer with his experience and reaction to the 3 months he spent in Rwanda after the genocide, as well as to open up questions to viewers about possibility of global denial of ignoring violence in Africa within Western Media and global politics. He visited Rwanda with strong conviction to express his solidarity with the people and met, talked with and photographed many survivors as well as the landscape of the genocide.

What I really learnt here from the perspective of the artist as a ethnographer is how this artist considered image consumption and resisted to make a spectacle of the violence that was so real. He took time to absorb what he saw and experienced, but does not shy away from his outrage and shame and having something to say about it. He considered a conversation about violence, without recurring to violence – to me it shows respect to the suffering of the victims and their dignity. He used the denial and indifference that happened (reaction of the world) throughout his work by resisting to make visible the very same denial. Most of his images are also about ‘hiding’/ silence.

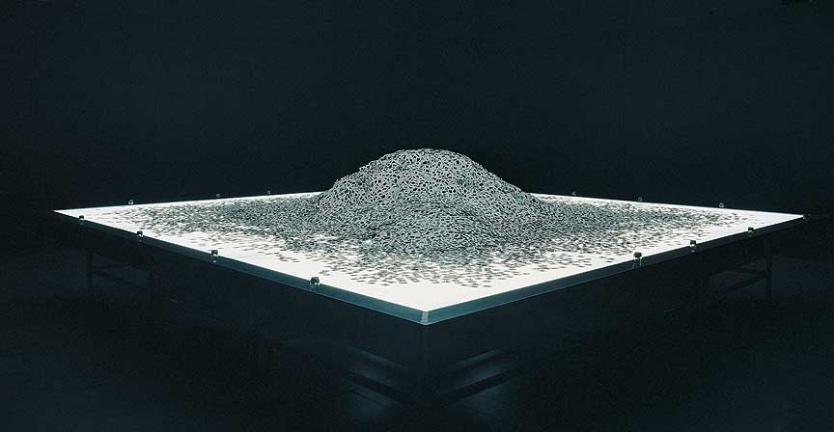

I read that he considered the space of how and where to tell/show – the rooms are all dark, the light reveals horror of what was witnessed by Rwandan people and others who did look – things we (I) do not want to see or witness. I assume there can be multiple interpretations as well as projections on the work presented, but it stays a topic of trauma which one clearly understand is almost unrepresentable and was ‘silenced’ , knowingly and even ‘orchestrated’.

If I look at above shown works:

In the printed text work he uses bold letters and repetitions minimalistically to make a viewer go and look for the why behind the ‘propaganda’ shown in the streets – even though you can be so far apart from it. I see a link with a commercial aesthetic in these prints , and here people going on in their daily lives were encountering this very ‘thorny’ issue which happened in Rwanda. The other two images tells the story of a young (5 years old) survivor who saw his parents being killed and became silenced (emotionally traumatised/shocked/dumb) for 4 weeks. The slides are just randomly thrown on the light table and with the single image, the eyes of the boy Nduwayzu, he tries to bring balance and content to the reality of what happened, but through the eyes of a victim. As a human it is difficult for us to comprehend that at least a million people died – we tend to make it abstract and the enormity becomes meaningless. I think it is very much the same thing that is currently happening with the Covid 19 pandemic (or wars, violence, etc) – how to deal with the crises as an artist? By using just one victim, the viewer gets to know his story and cannot walk away dismissing the image viewed on that table.

As an artist from a different culture and country, Jaar went into the project knowing and wary that he could make mistakes, but committed to become involved and through his response trying to say something that could lead to change. He became a social activist in the process of working and making.

During the course I was made aware of mistakes, being truthful, searching in my research and work, as well as being directed by my tutor to show up in my work – which is what this artist did. He did research, accumulated information (field visits and took more than 3 000 images, talks), analyzed and reflected on. I agree with his words during the (recorded) conversation ….”do we have a choice, should I not condemn? Should I ignore because I am not one of them?….I want to respond to the context of the world around me, even if the world prefers to look the other way.” and also “…I am not participating in this pornography of violence, I am doing something else”

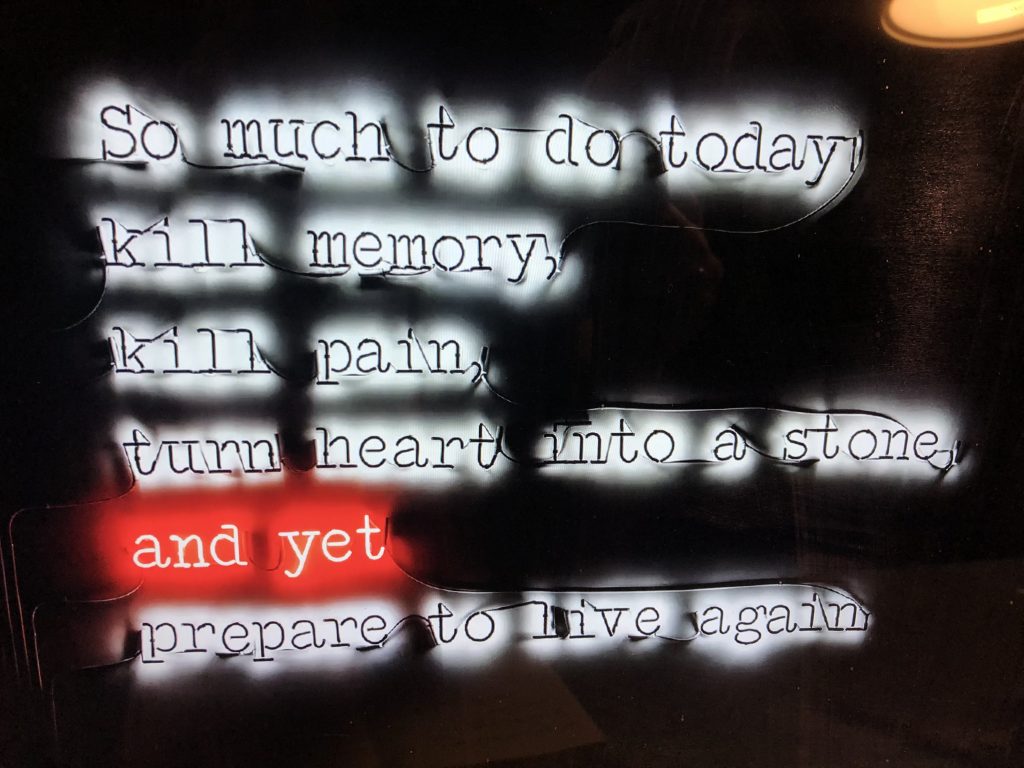

I want to say that I believe culture can affect change – we can show possibilities and install hope, but we also have to face reality and accept that sometimes you can do nothing about the ‘other’, but that should not stop your efforts, because tomorrow you might be able to do something. He had a part of a poem by Anna Akhmatrovo (I later find the full poem, called The Sentence) in Neon in the exhibition and these words are very powerful:

Cummins, Emma 2010 , Art, Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics, published in Canned Magazine, Issue 01, December 2010. (online access through the blog of Cummins

Interview with the artist in Art21. org (online published) and Zeitz MOCAA Instagram images and Zoom meeting where the artists discussed his work ( 25 February 2021)

Exercise 5.10

Kester sees more ominous forces at work and compares the role of community artists to 19c reformers and social workers. These marginalized groups can be rescued from their predicaments and transformed through cultural engagement, which is a way to avoid looking at the actual causes of inequality. Kwon proposes that ‘some artists have noticed, community based art can function as a kind of “soft” social engineering to defuse, rather than address, community tensions and to divert, rather than attend to, the legitimate dissatisfaction that many community groups feel in regard to the uneven distribution of existing cultural and economic resources.’ (Kwon, 2004:153)

Find a text that counters this view and then describe a model of community collaboration in your learning log that seems to avoid these pitfalls.

I feel that in my discussion of the next exercise I will cover most of these pitfalls and I am thinking under the influence of the ideas of Trinh T Minha ha. I read the following comments made by her, which I found very powerful:

“As the feminist struggle used to remind, the personal is political. Not because everything personal is naturally political but because everything can be politicized down to the smallest details of our daily activities. “It’s the little things citizens do. That’s what will make the difference.

My little thing is planting trees,” said the late Wangari Maathai, recipient of the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize and founder of the Green Belt Movement in Kenya; the movement became a tool to fight for women’s rights and democracy as it spread to other African countries, resulting in the planting of millions of trees.”

Exercise 5.11

Research a community art project in your local area, if you can find one, use this to address the following questions, otherwise consider them in a more general way. Are you able to bring any special knowledge to the project and the community that others might not have? Does it matter if the artist lives in the community? What might be some of the problems of an artist working with a community group that they have very little, or no prior connection to? Present your thoughts in your learning log.

I looked at a project that started in the town where I will be returning in April this year. The work was commissioned by Arts Town, Riebeeck valley, a local initiative to revive tourism in the town, and conceived and conceptualized by local artist, Emma Willemse in collaboration with a local community art group, The Arteri, during the lockdown period in South Africa (March – Sept 2020). The site-specific public sculpture installation is situated in and around an outdoor amphitheater in the gardens of the Royal Hotel in the town of Riebeeck Kasteel and is known as RATA (Royal Arts Town Amphitheatre)

Stone Circle is the first of a series of sculptural projects. The goals of the project are to uplift as well as transcend viewers and audience, and foster community involvement in the visual arts, and transfer art-related skills to the young generation of the area. This project consists of two components, the Boat Circle and the Amphi Circle.

The Boat Circle can be seen in the above aerial image as it is placed in the labyrinth made of white pebbles. The boat overlooks a dam and the Kasteelberg mountain – this is also where the stones for the boat were collected. The boat and path side is 20m x 6m. According to the artist, who is known for employing the motive of the boat in her work, the boat has always in history evoked rich metaphorical associations, like being a vehicle to transport humans over water with the cargo-carrying our hopes and dreams- future expectations. Linked to the Covid-19 experience she sees the boat as a visual weight that is filled with stones that stand or evoke our restrained movement – almost immobility. There is also the symbolism with stones which centers around, endurance, permanence, stability, resilience, survival, and eventually hope for things to change. Visitors are invited to add stones when they walk the circle to add to their own ritual of remembrance.

I read about The Amphi Circles on the artist, Emma Willemse’s webpage: “.. 16 stone circles, constructed with stones collected from the Riebeek Valley area. The circles serve as social distancing devices. Through a series of workshops under the guidance of Willemse, the circles were designed and constructed by The Arteri, a collective of young creatives in the Riebeek Valley community. Willemse had during these workshops, underlined the principles of involvement as well as share information about land art and ideas around values and collective decision to see the stones as temporary loans from the environment and to not install them with the idea of permanent fixtures. She helped with designs, like how to investigate ideas for designs in drawings, make preparatory sketches, looking at visual principles such as shape, line, and repetition into consideration, and the collecting of the stones, sorting of it – all about teamwork. Participants learned skills in this process. Photo documentation was used as a reference to build and install each circle. Respect for the environment was installed by using only stones needed, curb wastage and respect the natural environment from where these stones were sourced/found.

The community

The local community is small and situated around the two towns and farms where sheep, grain and vineyards activities are maintained. One cannot talk about much industry – a cement factory and Other cultural projects are a Garden Project, where locals have their own allotment vegetable gardens, the Steel Band Project run by David Wickham, and the Community Theatre., and the Open Studios by local artists, as well as Oukloof legacy, where a group of people came together to start of a process of collective storytelling – and hopefully of community healing and reconciliation after the coloured community was forcefully removed out of town in the 60s. The town Riebeeck Kasteel is one of the oldest towns in South Africa and currently around 3000 people live there. The poorer Black and Coloured people in the community has over the years complained about lack of housing and access to land ownership. The Coloured community was removed to a separate area, called Esterhof (history of dispossession in Apartheid regime, under the Group Areas act, is still an issue which needs attention and retribution, as well as recognition, being part of history and identity of the victims) On the Oukloof project website I read the following: “The coloured community of Esterhof is still very much segregated from the rest of the town, in name and location. Not much has been done to close this divide. Coloured residents refer to the railway line as an imaginary apartheid wall that is meant to keep them out.”

Mark G. Wilson (award-winning director) started RATA when he moved to the town two years ago, explained that he realized that there are still many problems around racism, lack of inclusivity, and real transformation. His response to this was to start a community performing arts project as he believes the arts (particularly performance) have the power to transform, heal and bring divided communities together. The Olive Branch Project was started in January 2019 and quite quickly became part of the arts and community scenes in the Valley. By the time the hard lockdown was hitting home, he was influenced by an article by Ismael Mahomed in which he posed several hypotheses around the reinvention and survival of theatre. Wilson realized that the town had an ideal open door venue to continue theatre events, once the lockdown regulations were relaxed. It was an area in the garden of the local Royal Hotel. The owner was excited by the idea and generously donated the venue free of charge and gave Wilson carte blanche to plan a theatre season. Below are images I took from the FB page to share how space is being used.

The project to create the works envisioned by the artist was discussed with the leader of the Arteri Group and she was asked by Wilson to involve her members and hopefully more local youth. The Arteri Group was then only recently formed as a youth hub with a focus on creativity. Their leader was asked by the artist to create 3 teams to work under an appointed team leader (experienced) and under the guidance of the artist in the effort to create the stone circles. It was difficult to get a commitment of the members/volunteers to follow through with the artists’ envisioned workshops – as many had other commitments or fears (work/study/family/fear of Covid 19). In the end, it was mostly students who were home due to the lockdown that could see the project through. Their background was in fashion, art, music, and theatre. The team members continue to receive a monthly stipend to maintain the circles, as there are now ongoing shows presented in the open-air theatre.

I believe any community project involves hope and expectations. It is clear that the initiative to create a series of site-specific sculptures came from the tourism need as well as a creative way to keep the local theatre shows going – outdoors was the ideal in the light of the threat of the pandemic. The artist saw her boat/labyrinth project as a way to involve viewers as well as giving them the experience of a ritual of meditation that could be linked to the epidemic, in which way you want to identify with it. The circles are a creative and aesthetically pleasing way to keep people socially distanced at these events. I believe the crisis on the economic and social levels which was caused by the pandemic had been made ‘softer’ by this vision. It however also showed the vulnerabilities such as job security, lack of education, and access to local government support. This is clearly a civic action and with the necessary empathy can grow into other much-needed change for the local Coloured community. I think it is good to see the value of collaboration as well, and I am sure there are shared lessons to be learned.

I follow the Riebeek Valley Olive Branch Project on Facebook Looking at a common problem of art activism, I would say it too often involve work conceived by wealthy outsiders, who want to keep control of these ‘projects’, questions arise like who delegates , who represents, who speaks, about whom is spoken and to whom is spoken to or on behalf of whom is being spoken?