4 October 2022

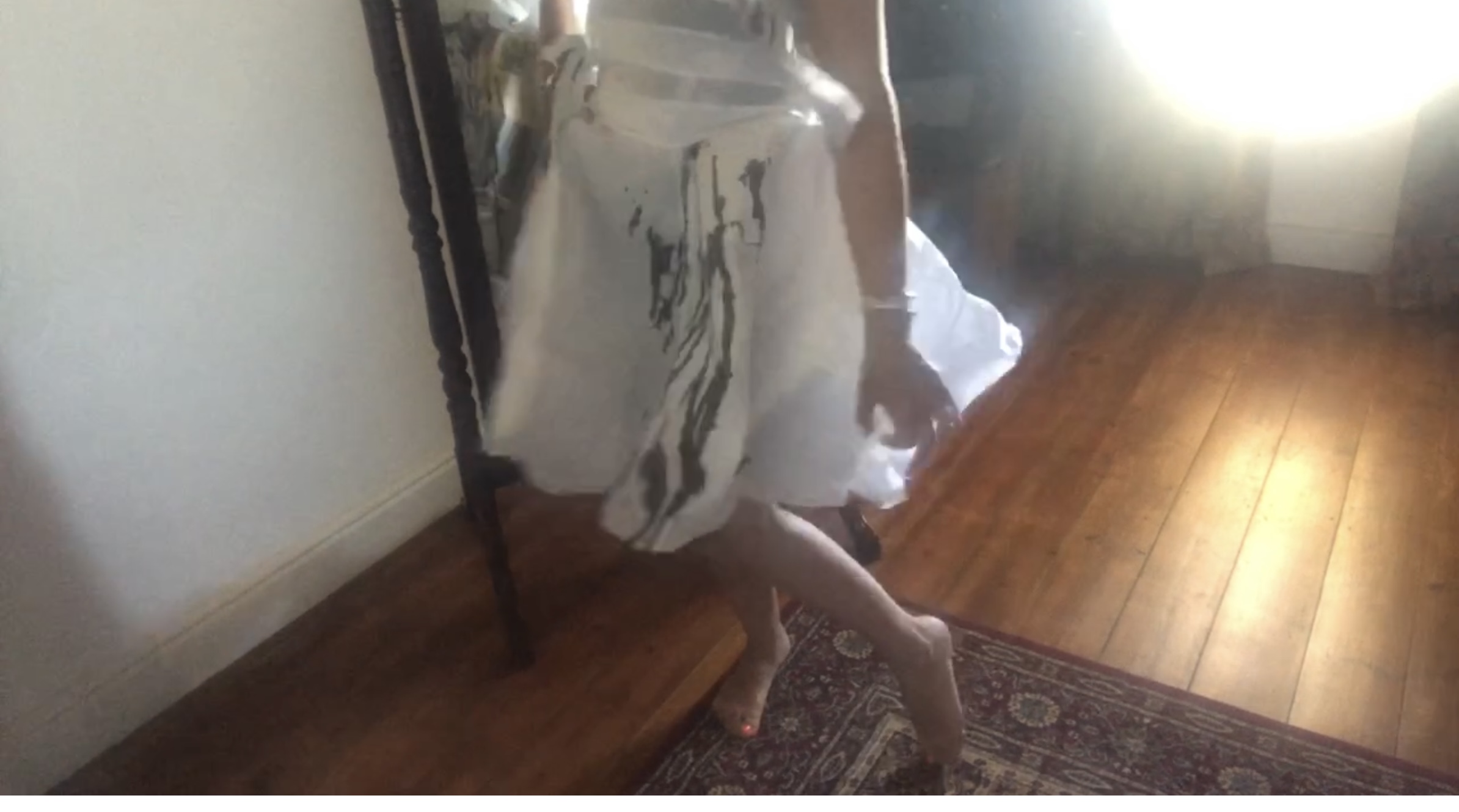

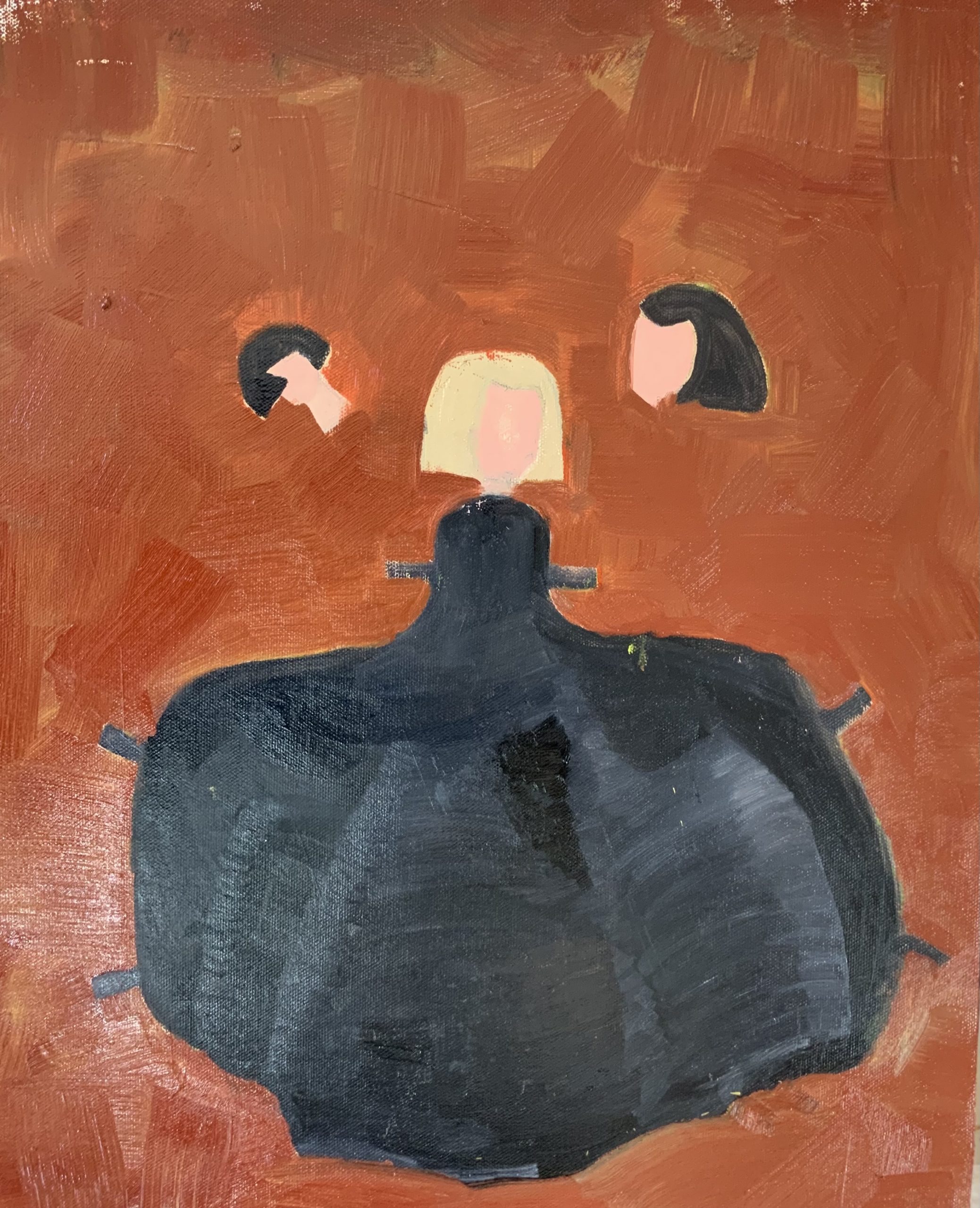

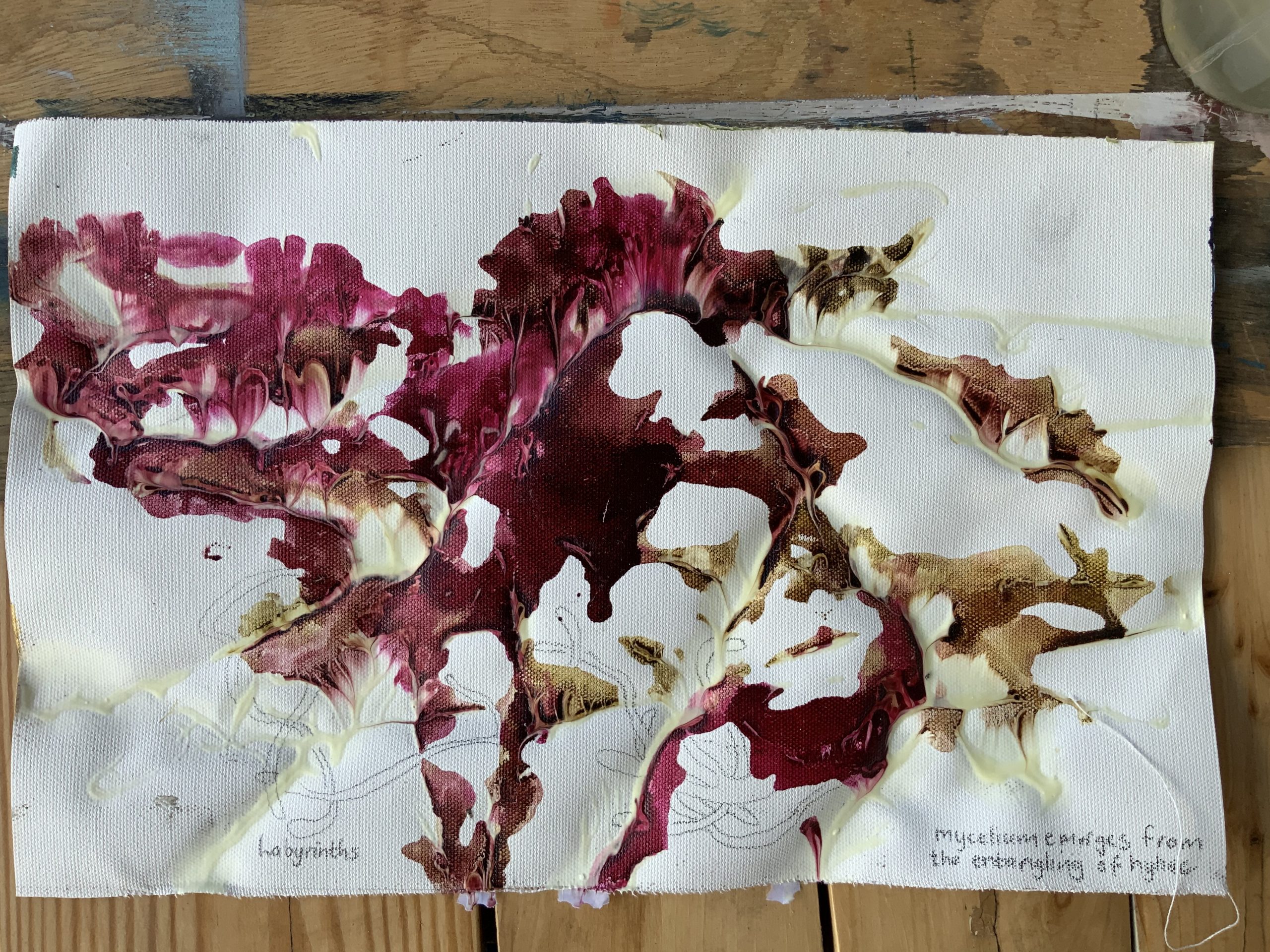

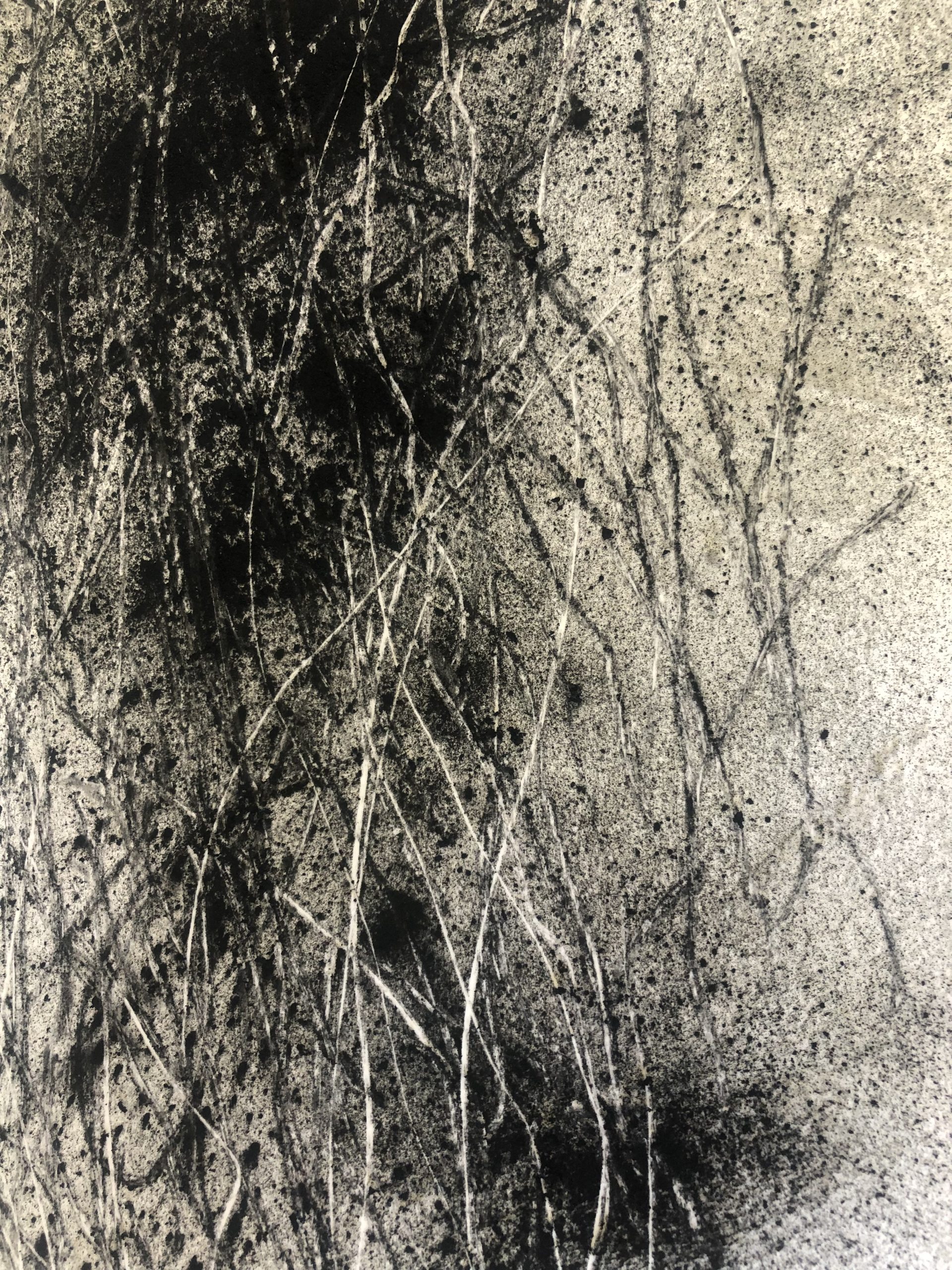

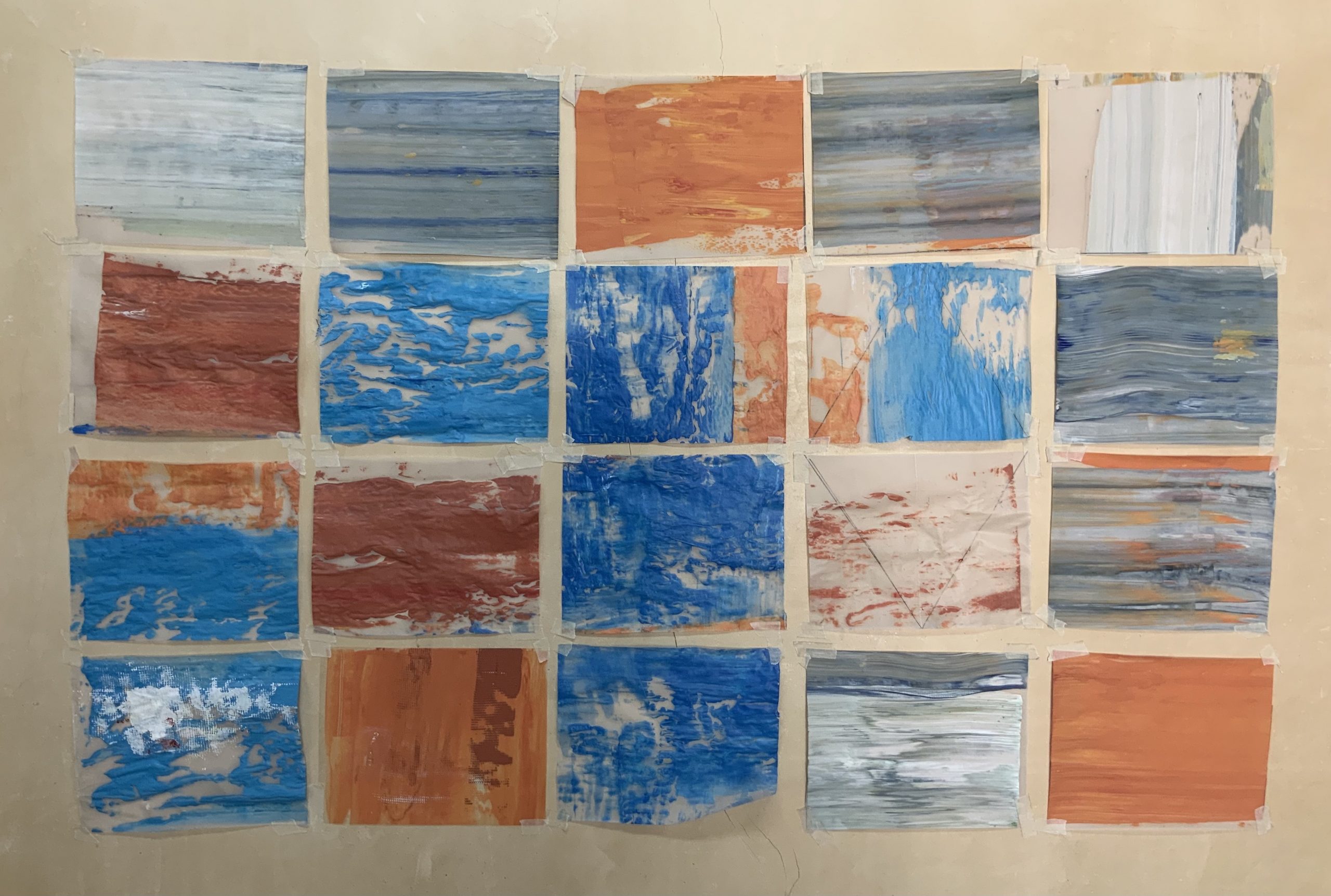

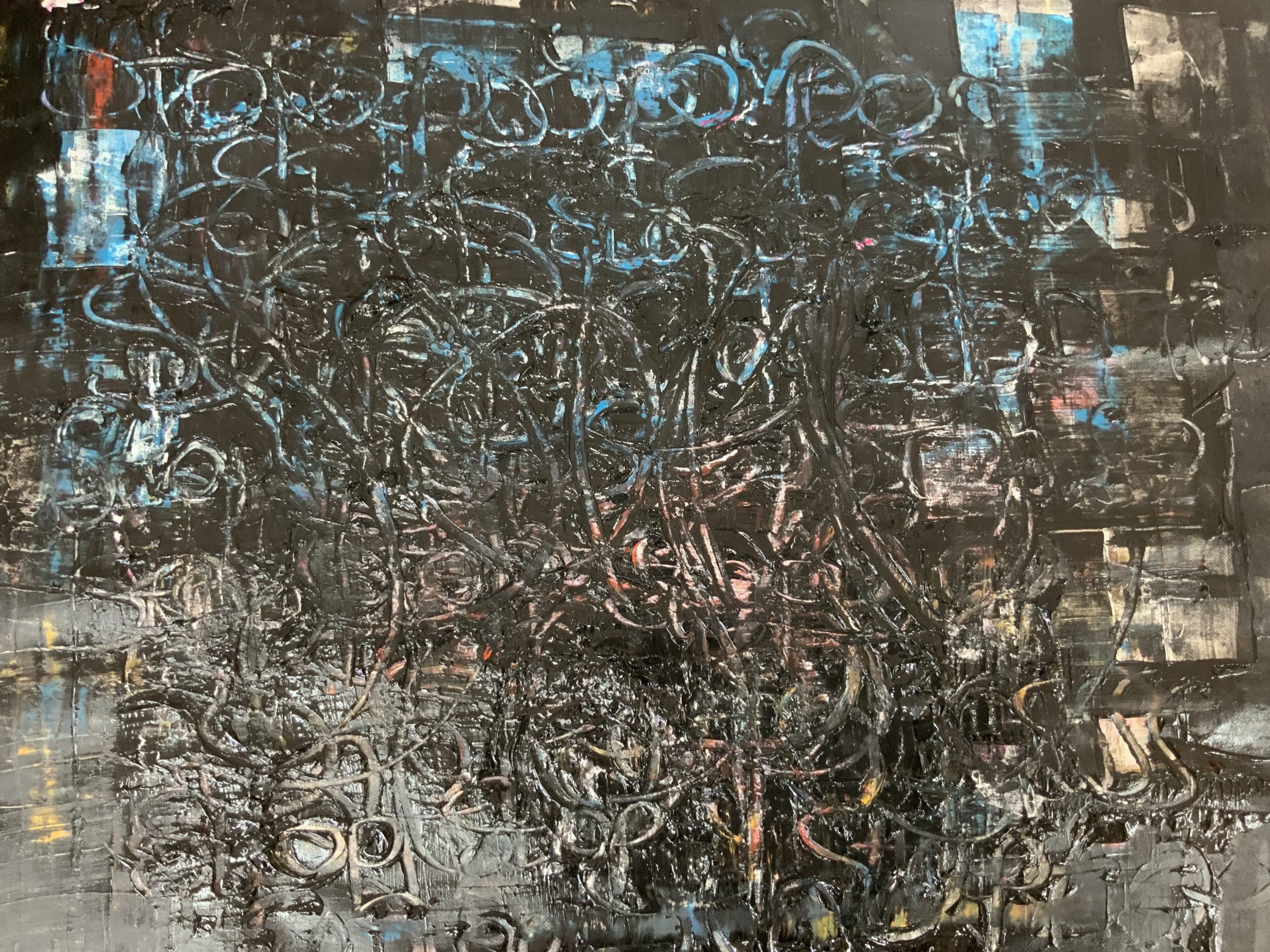

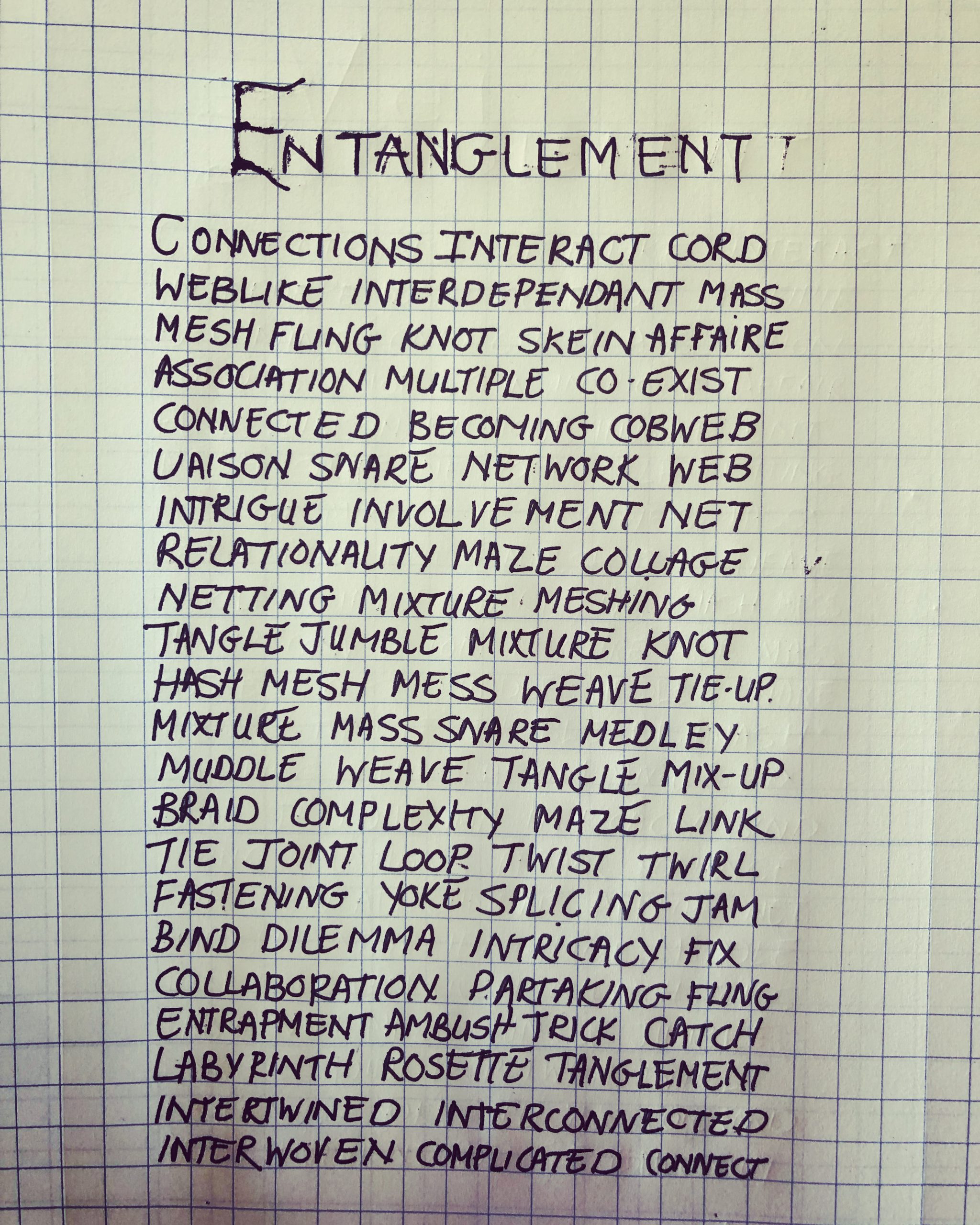

The body of work which I created for Studio Practice was informed by experimentation with gestural mark-making, painting explorations about space, bodily presence, materiality, objects and the agency of the non-living and text.

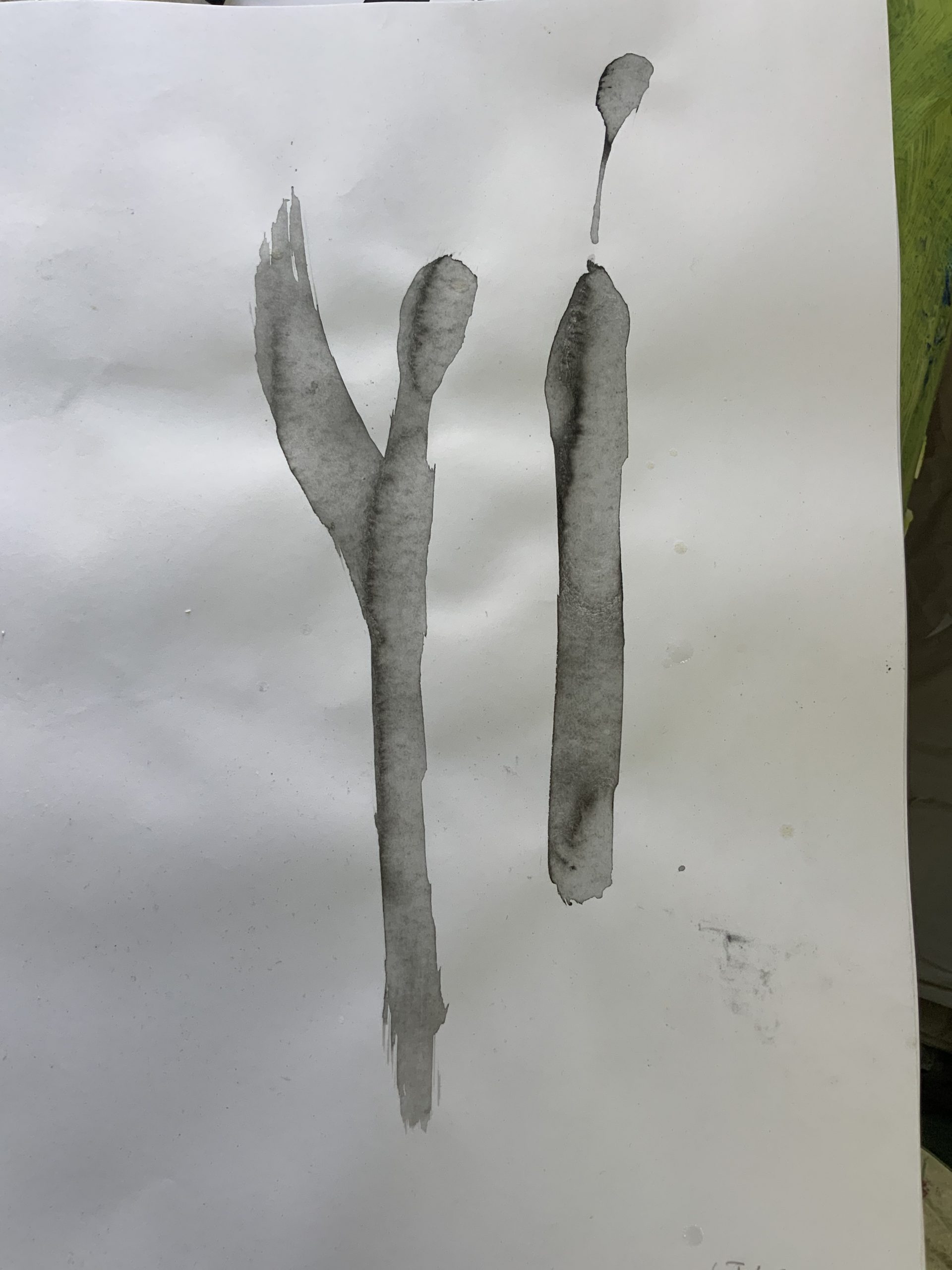

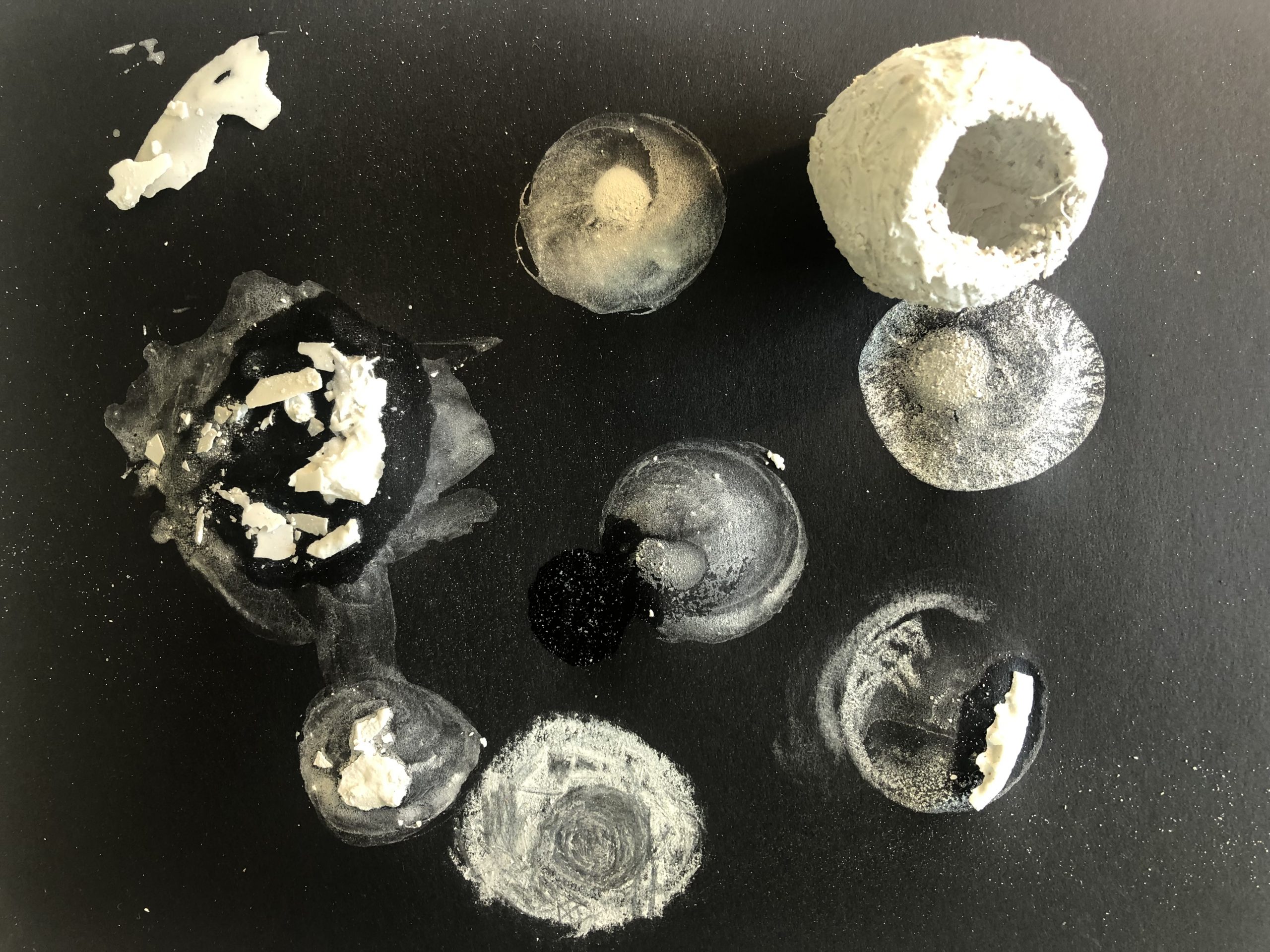

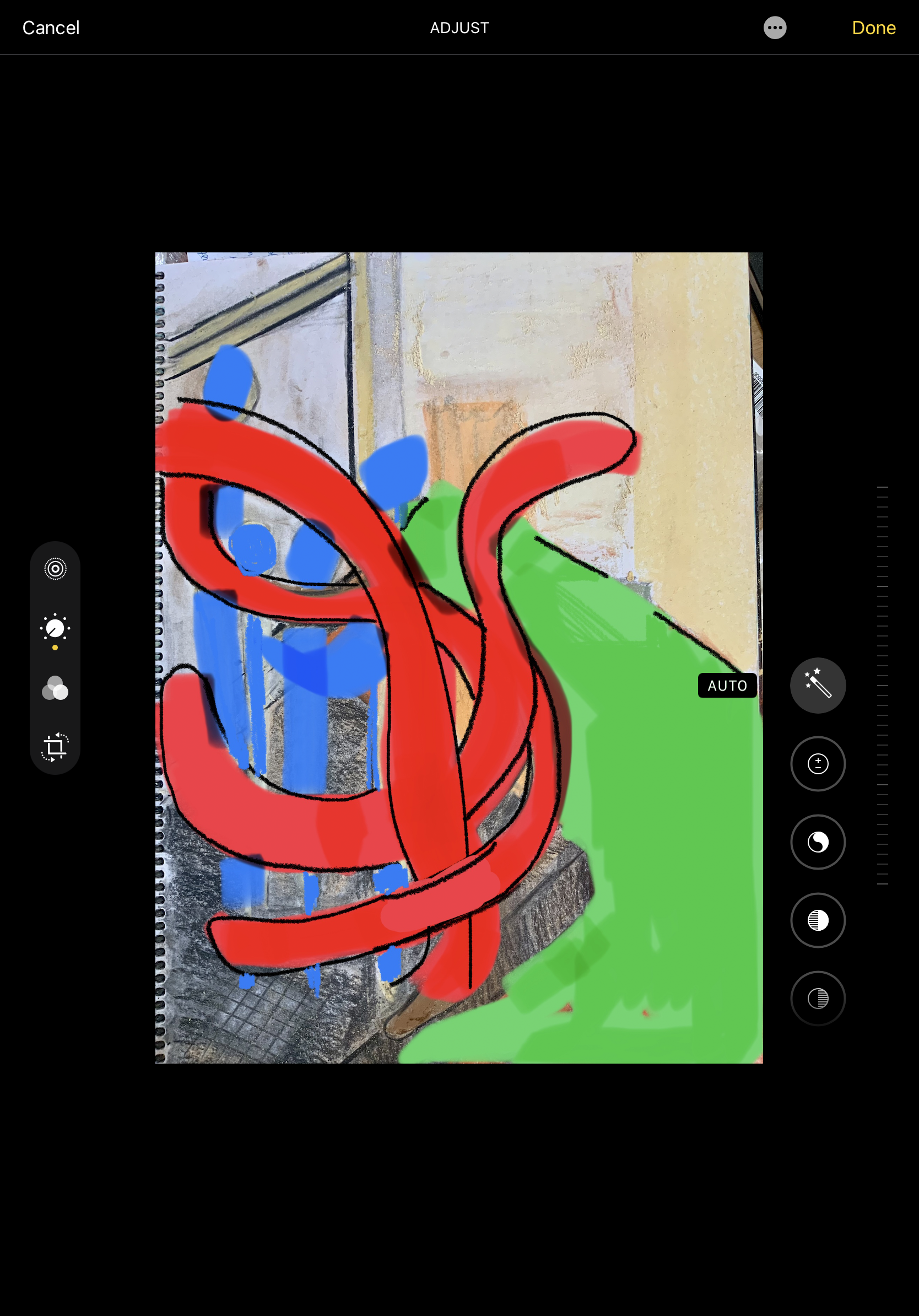

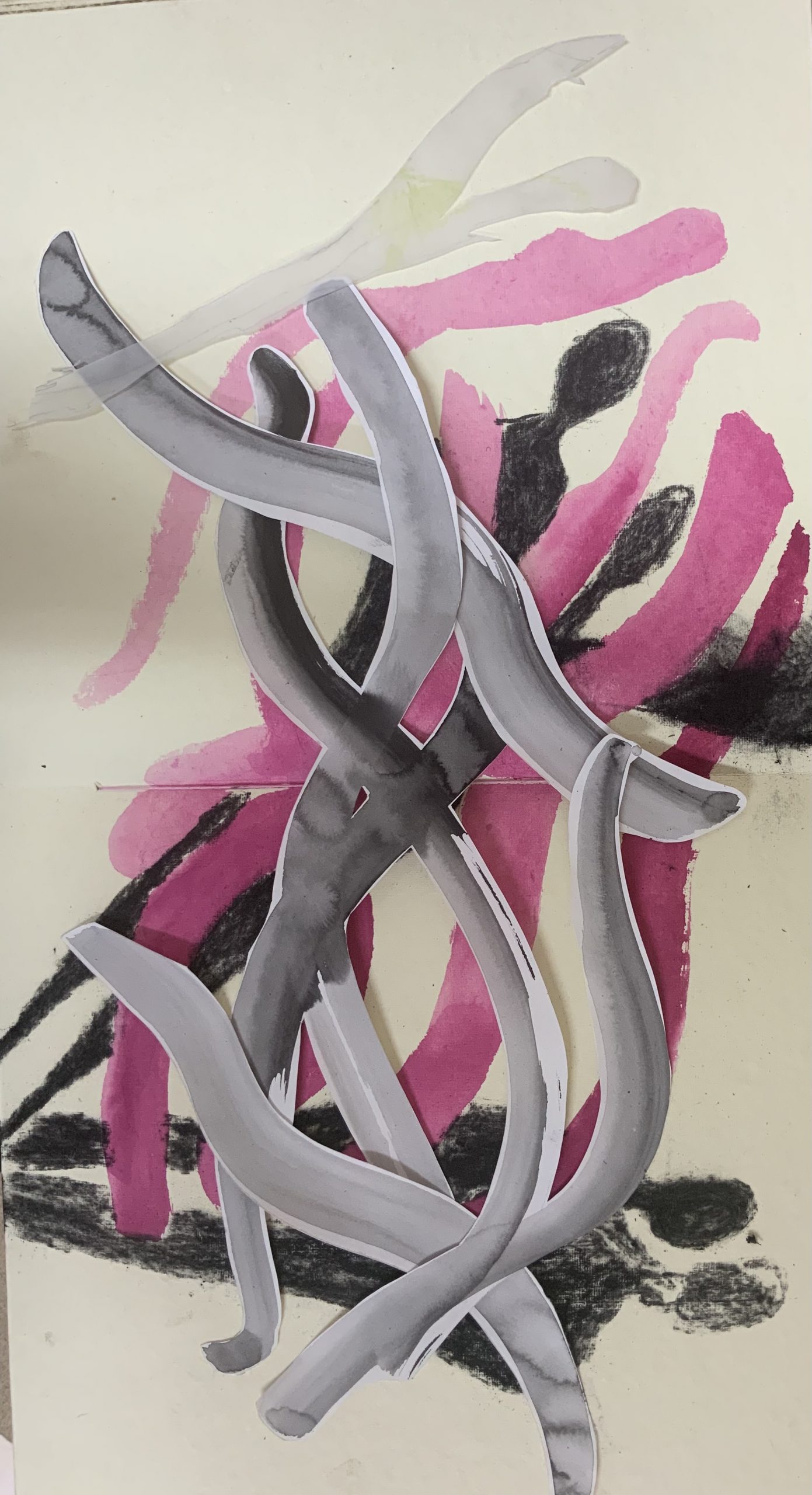

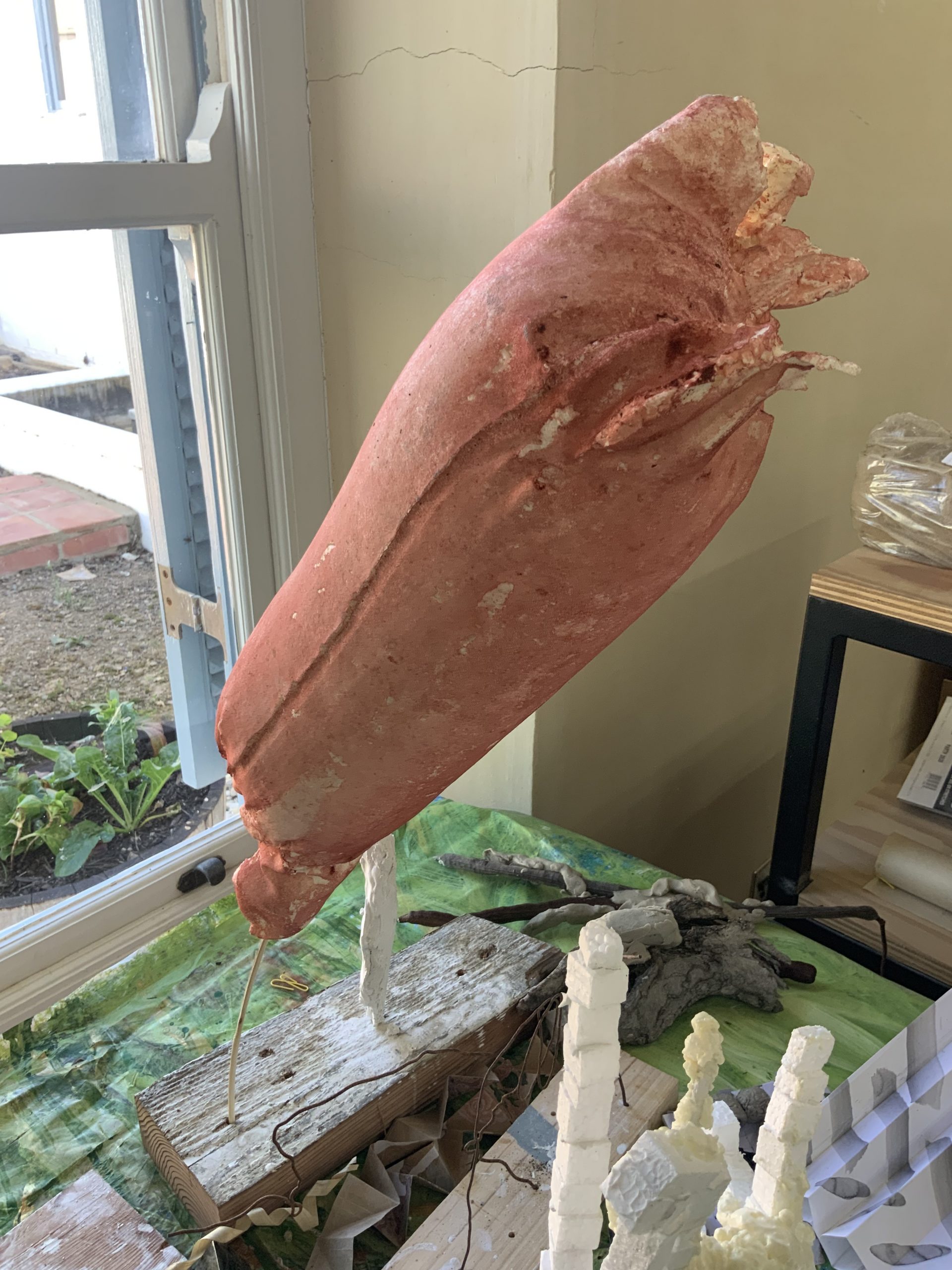

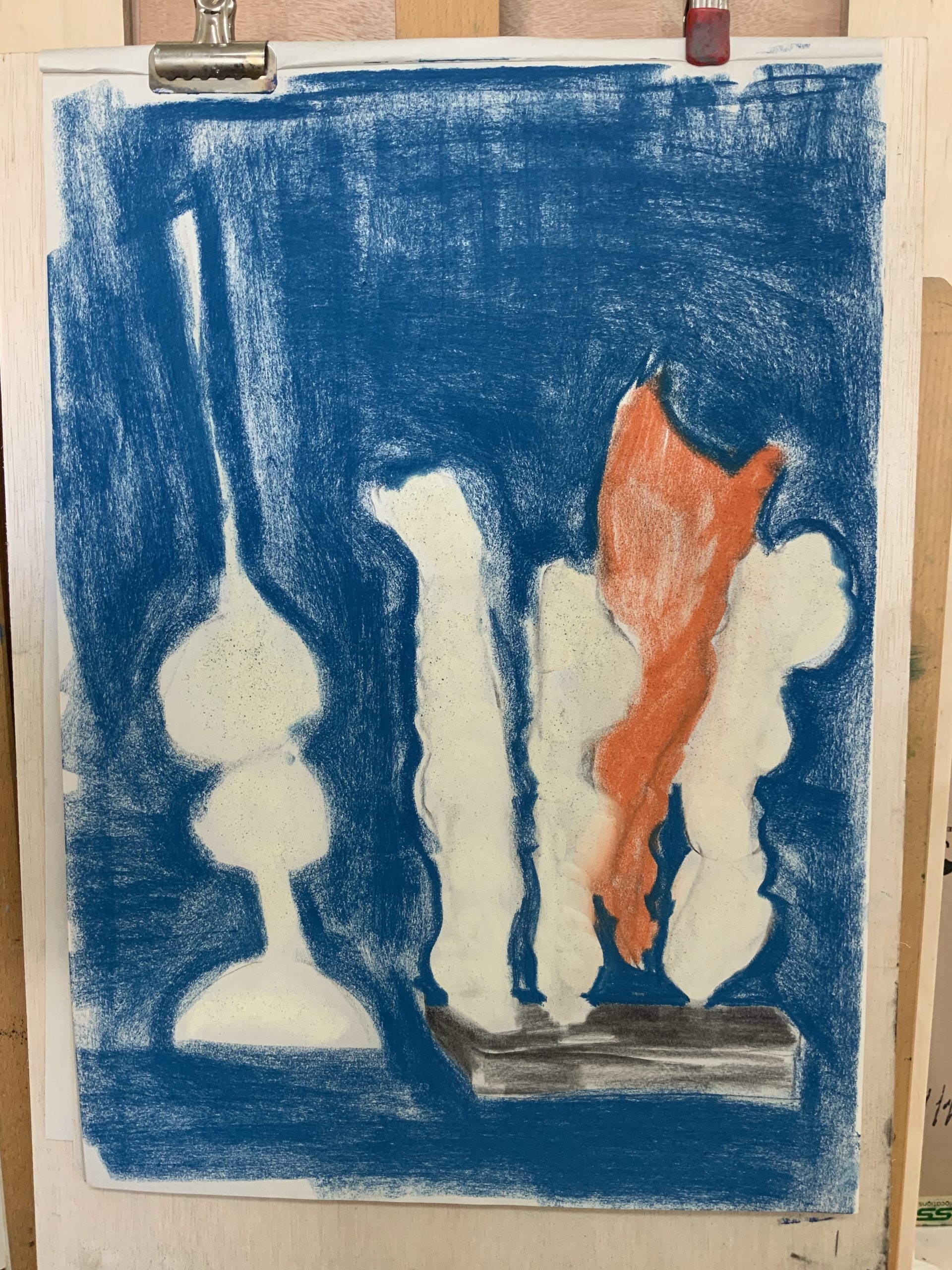

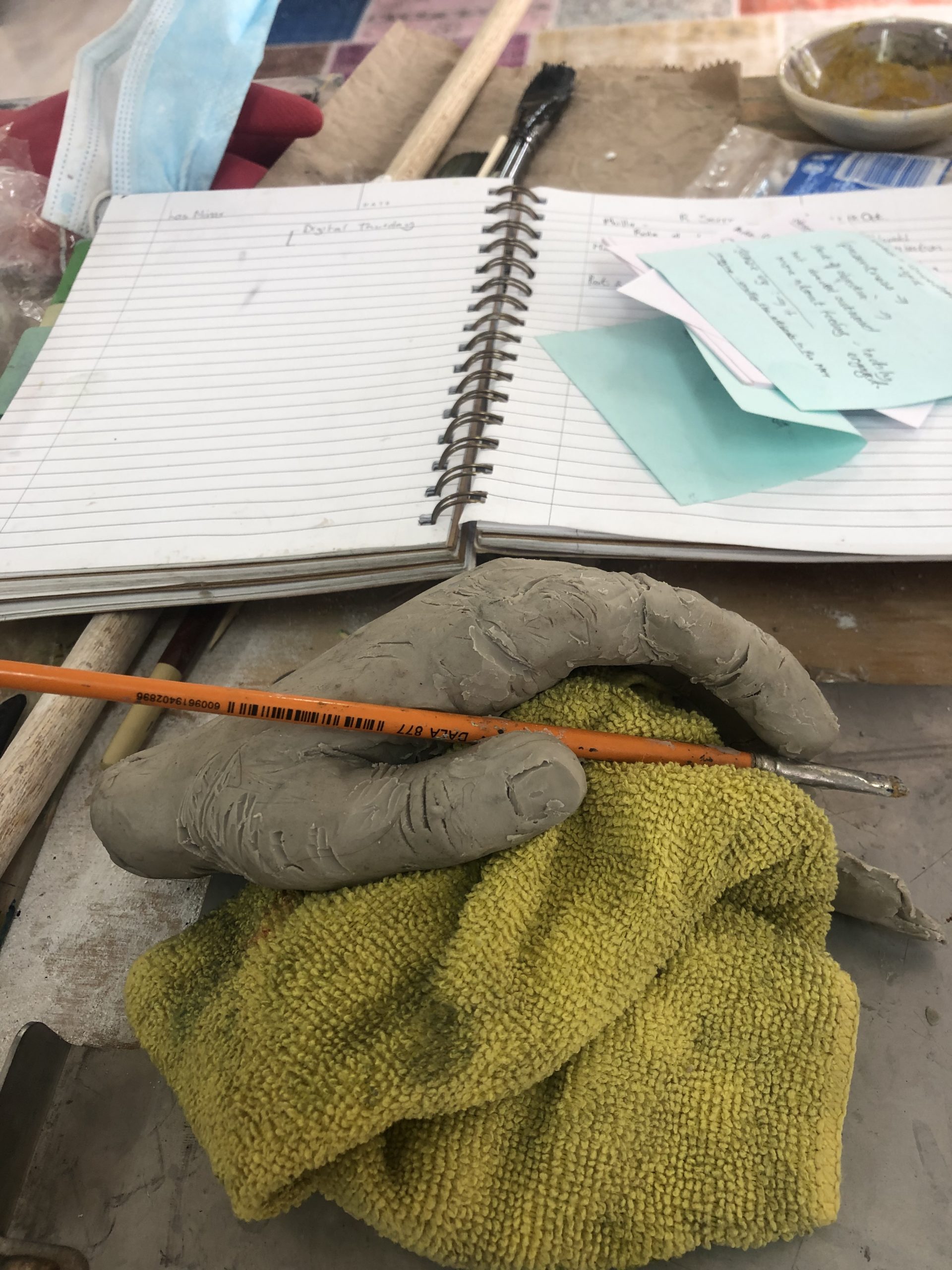

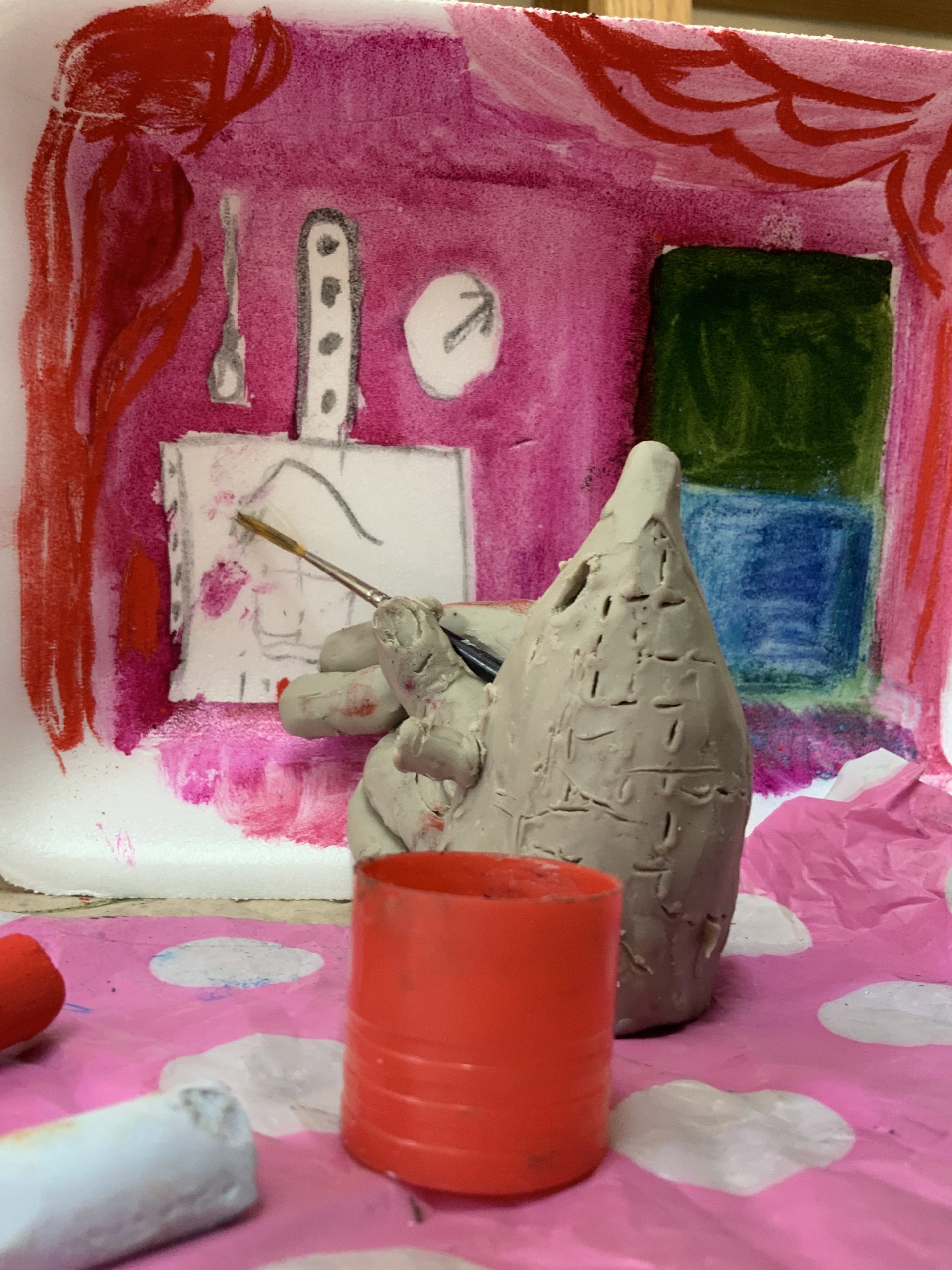

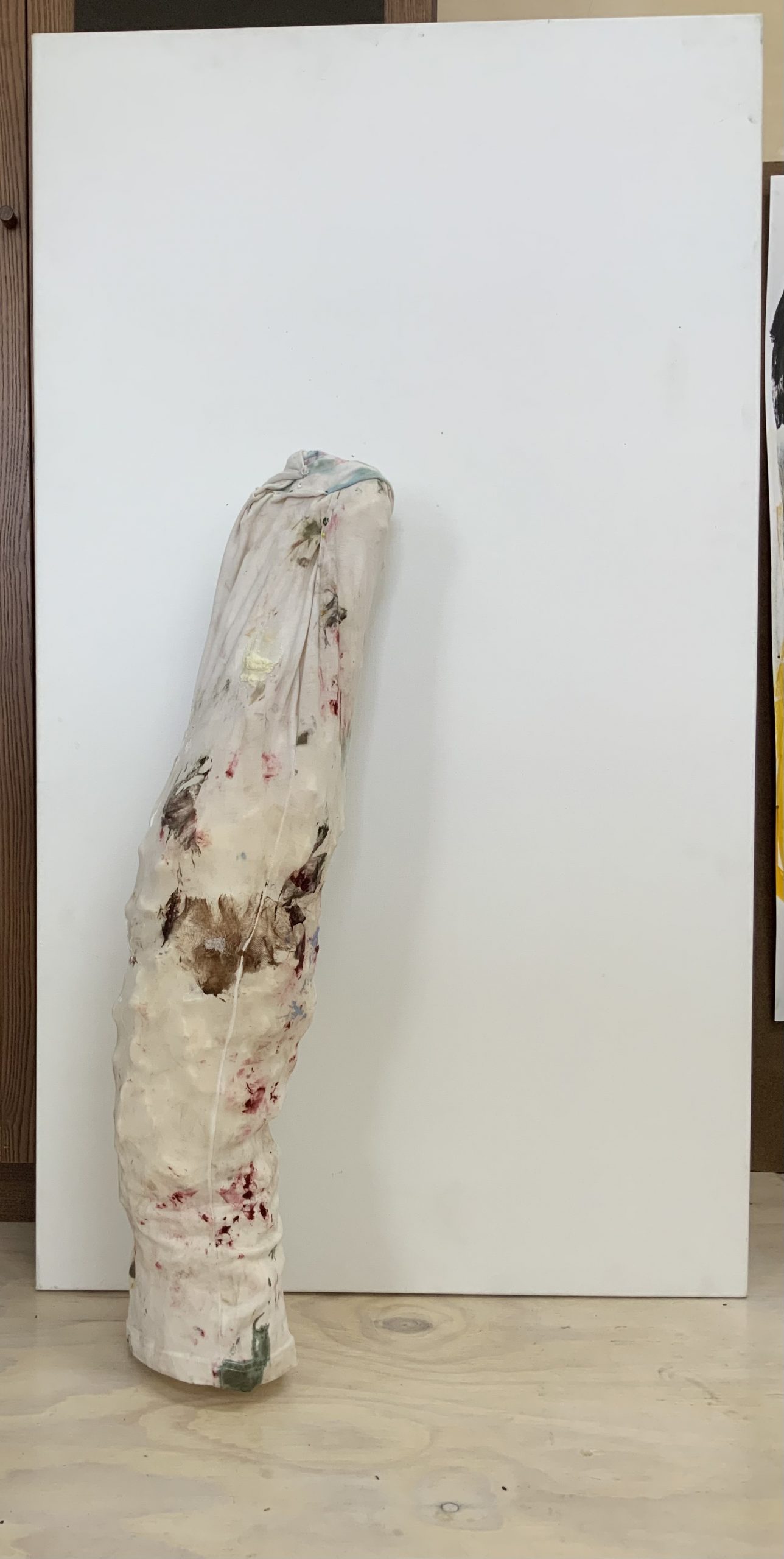

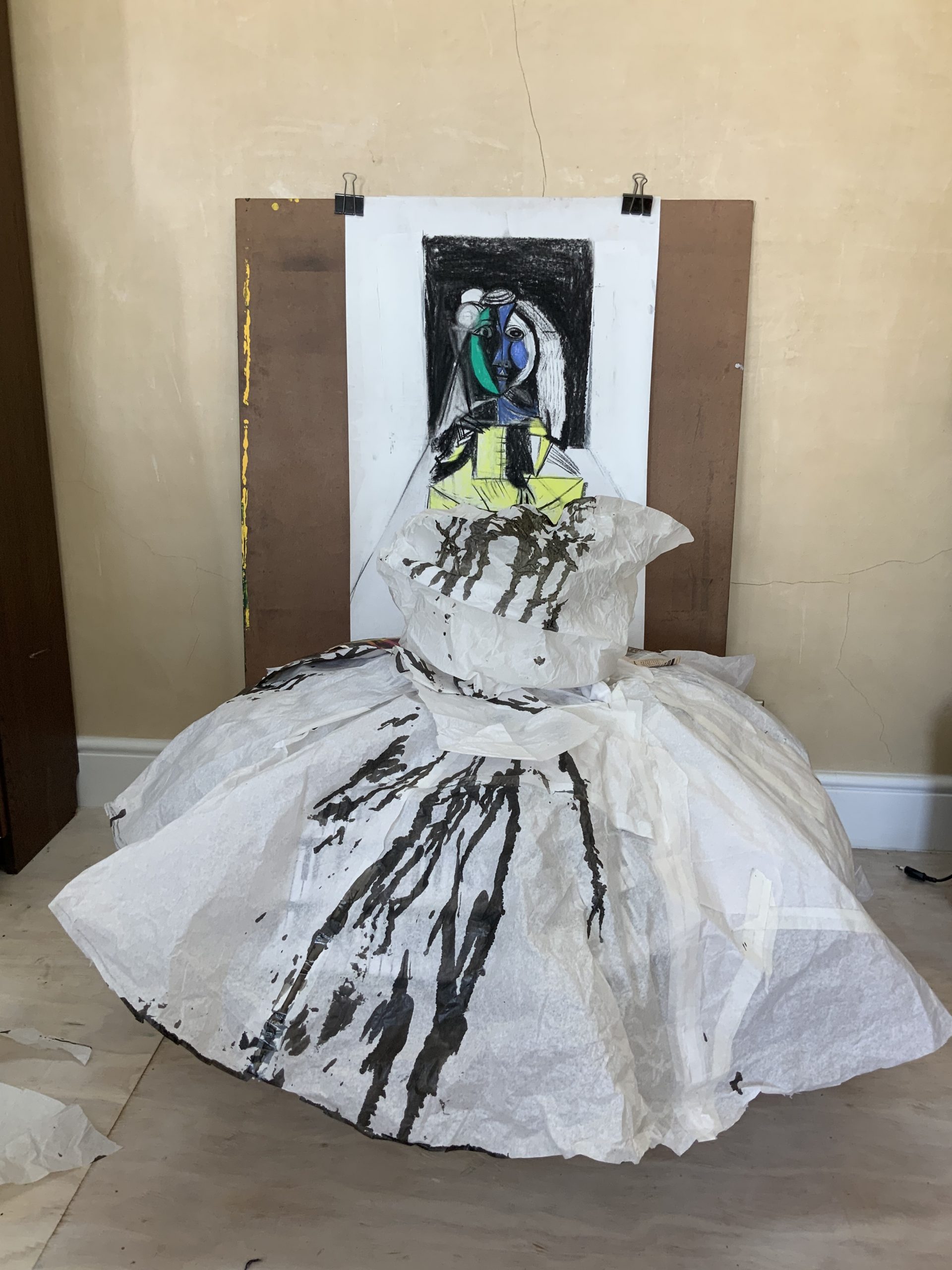

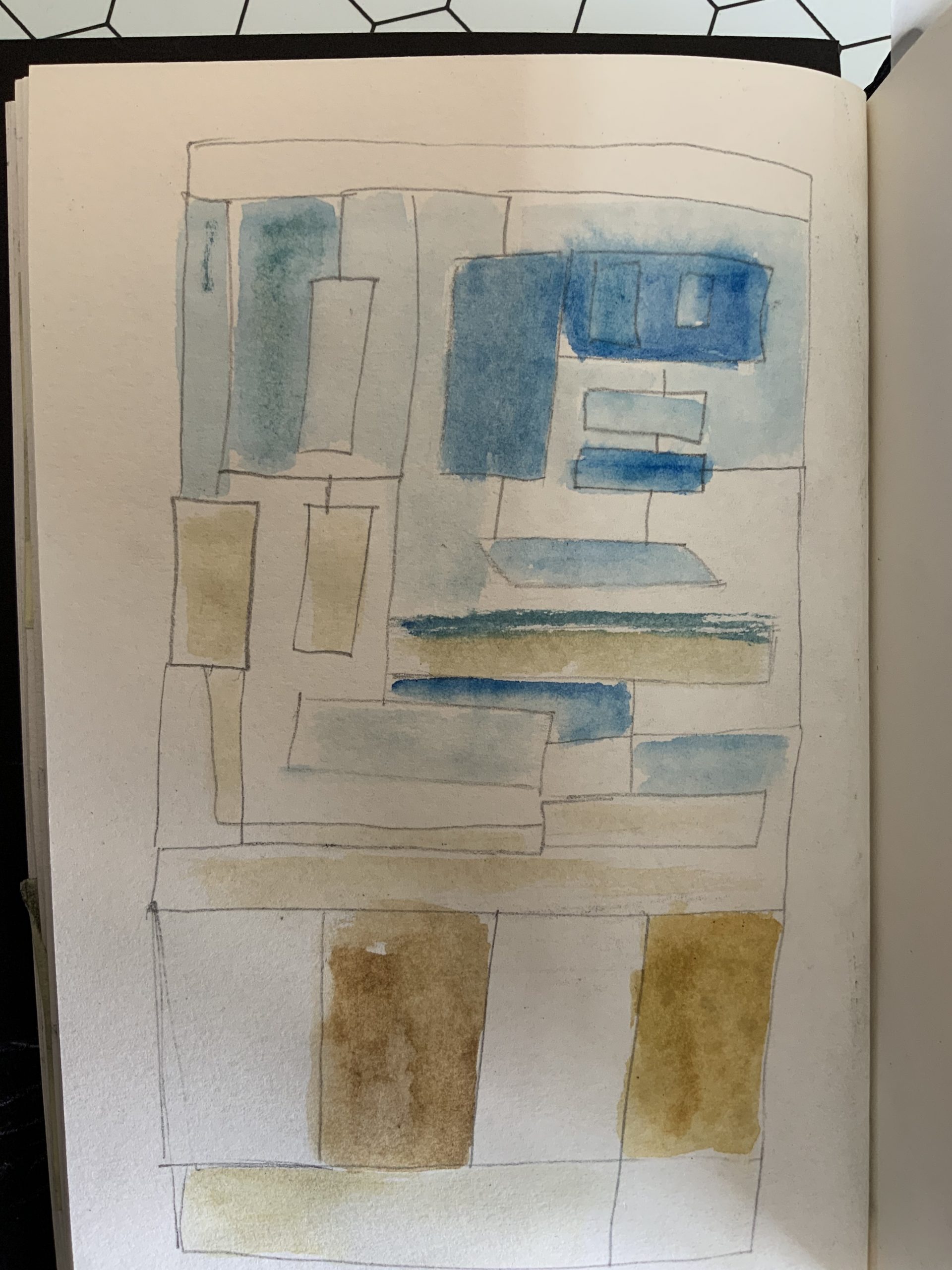

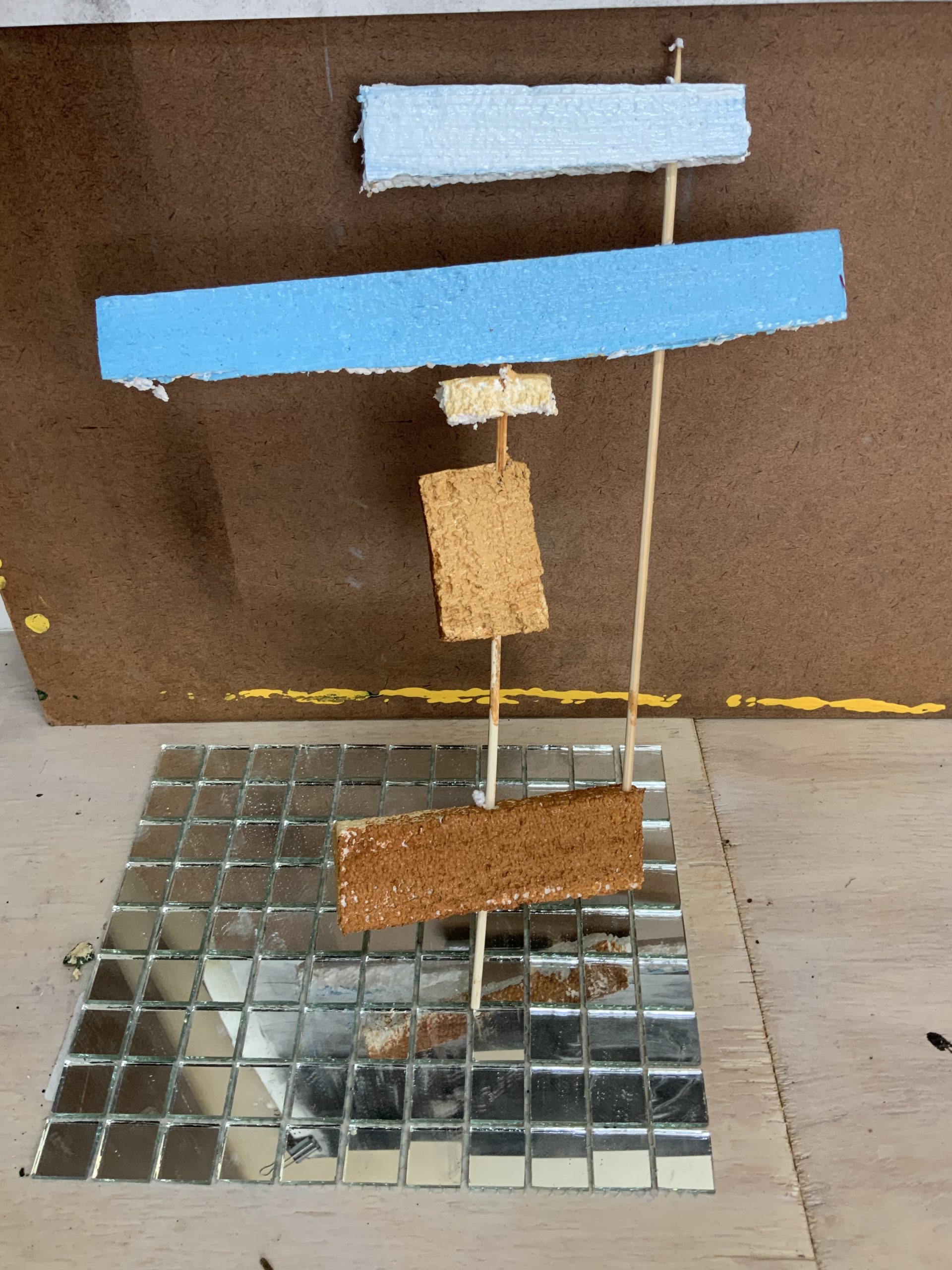

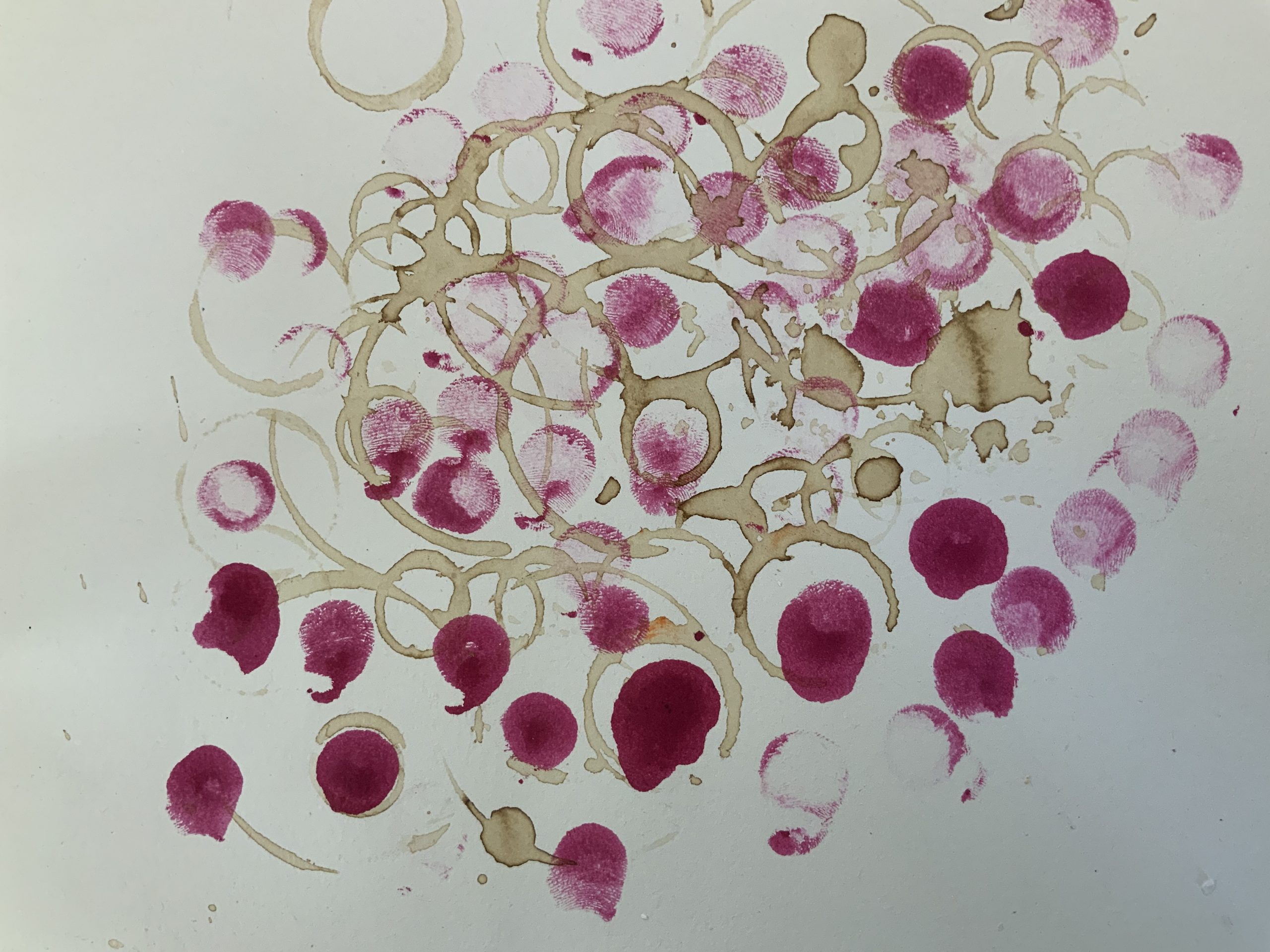

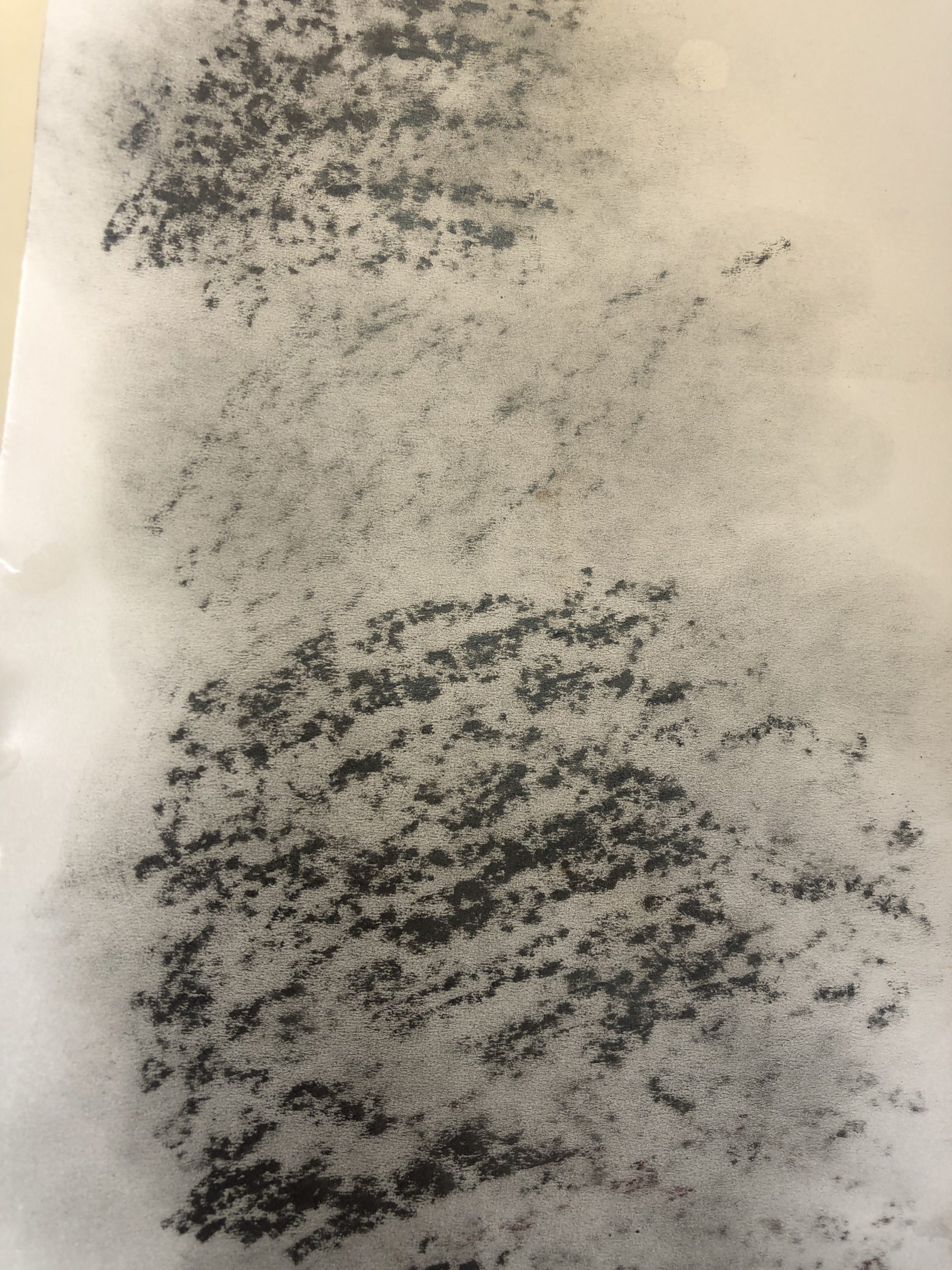

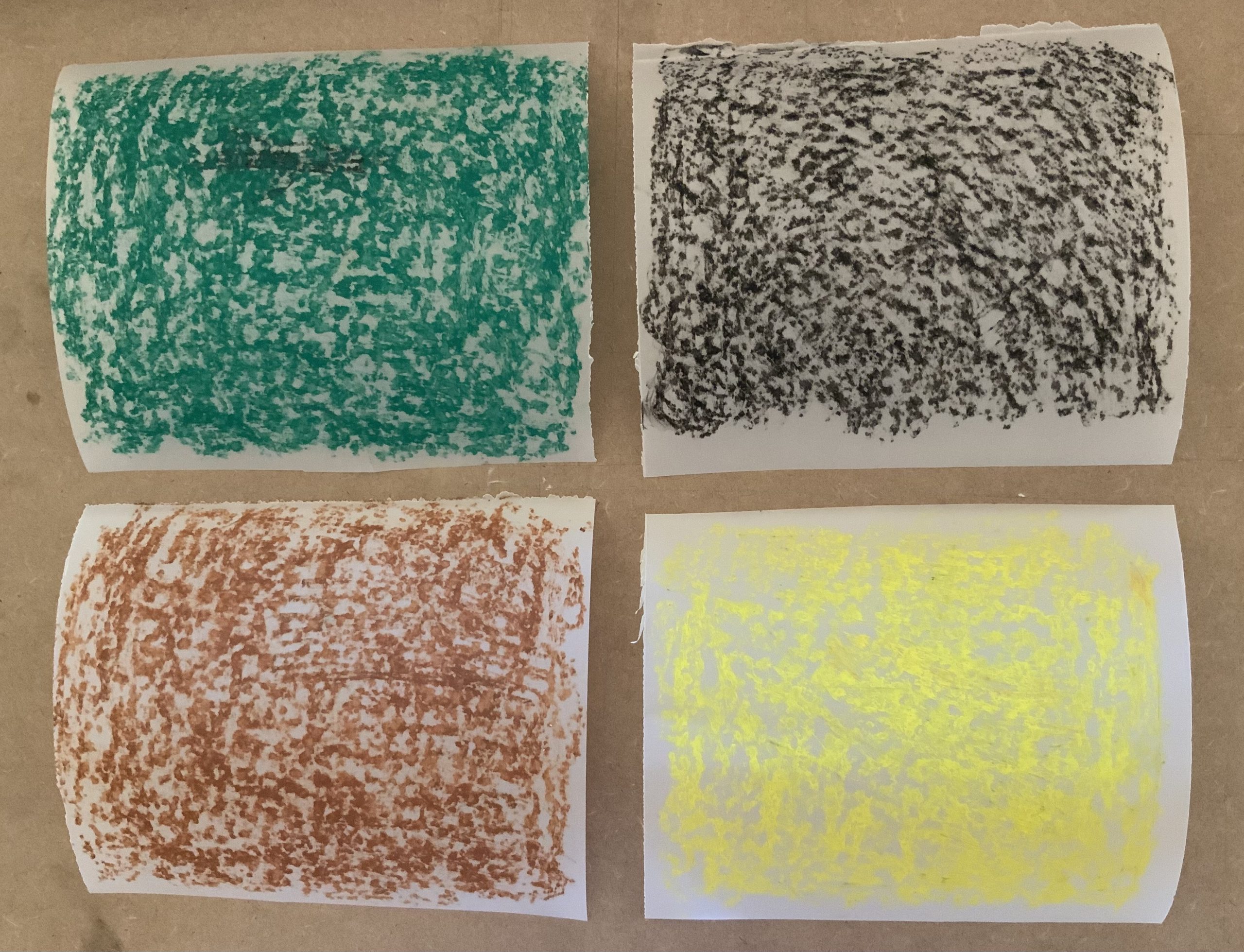

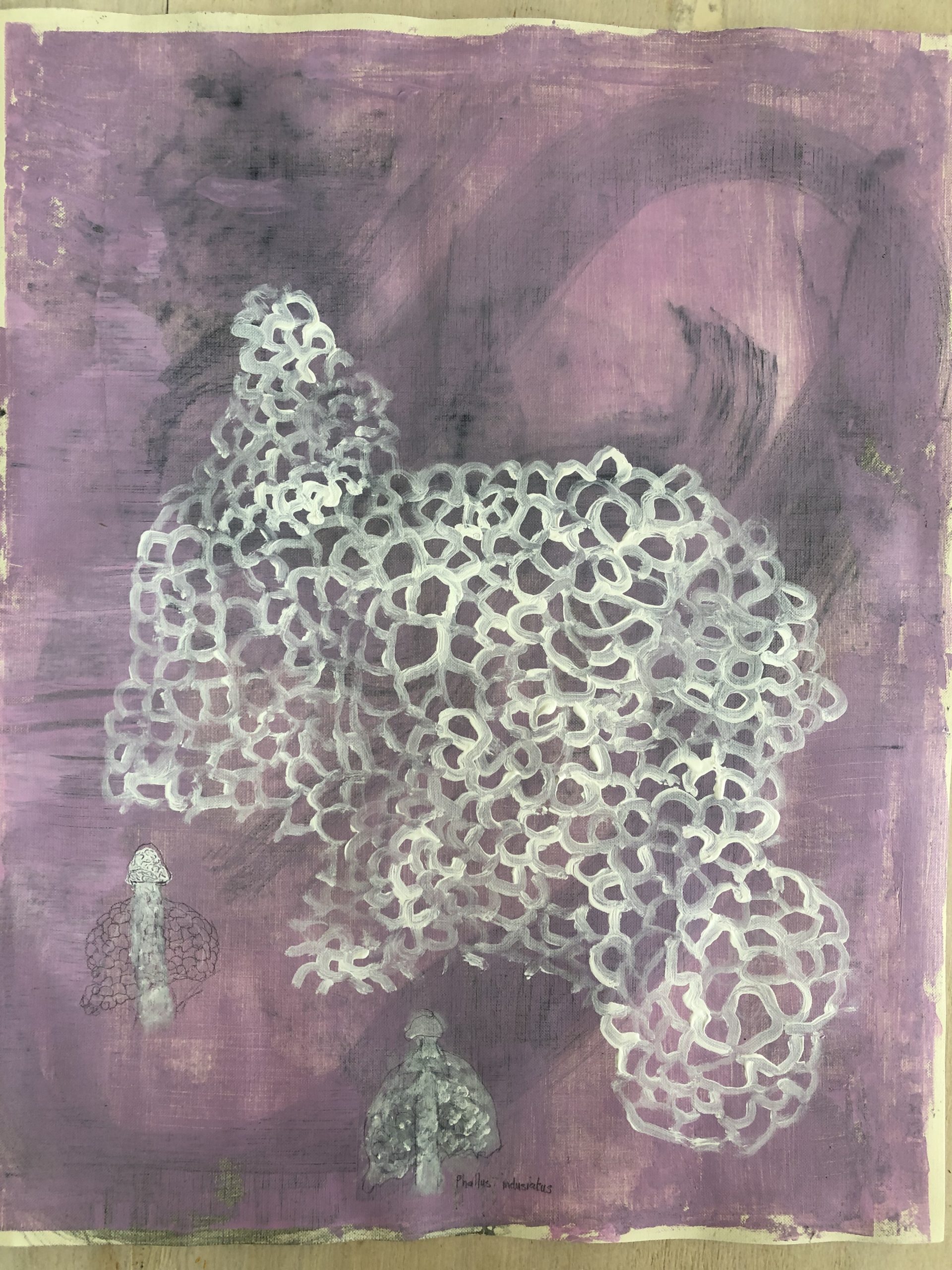

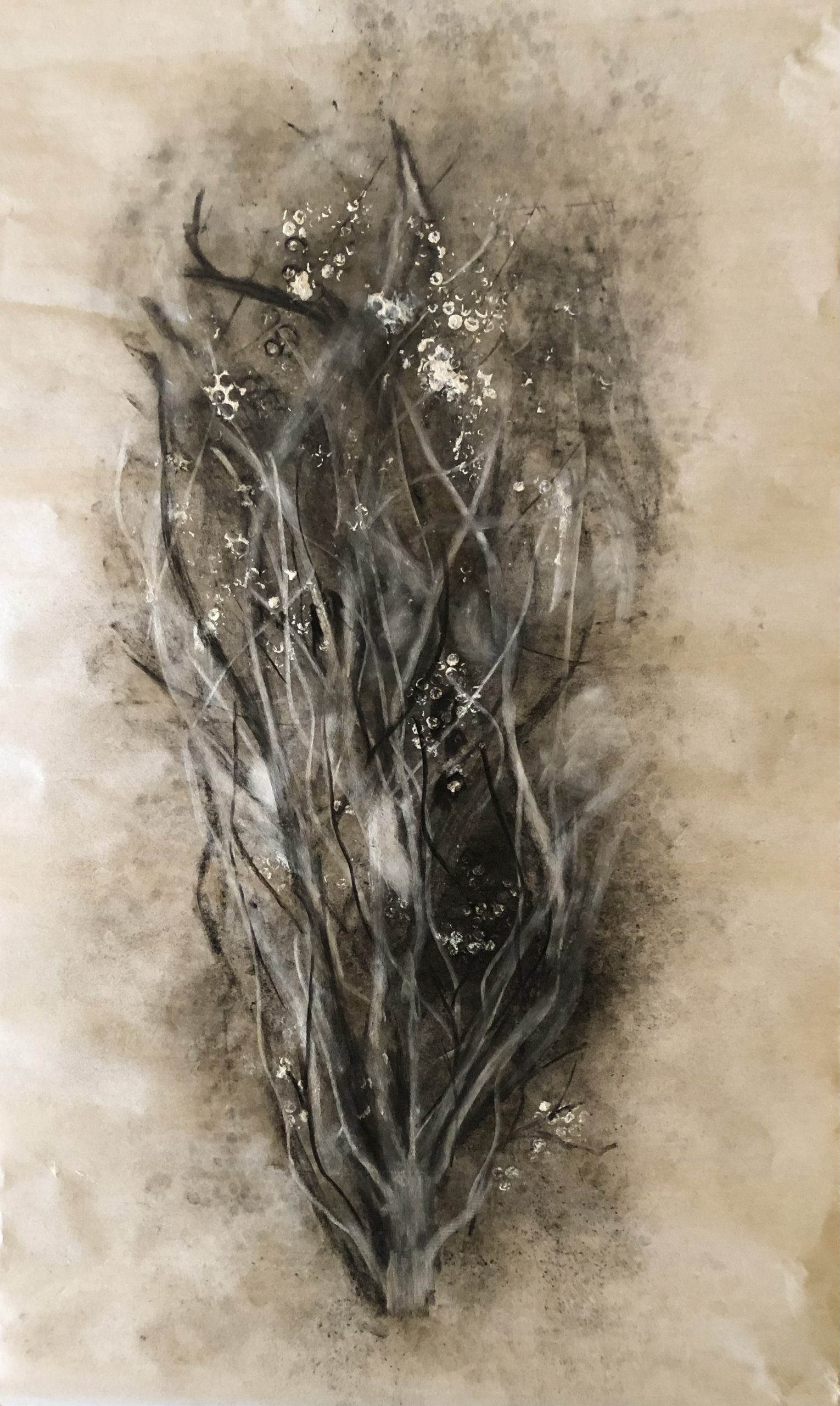

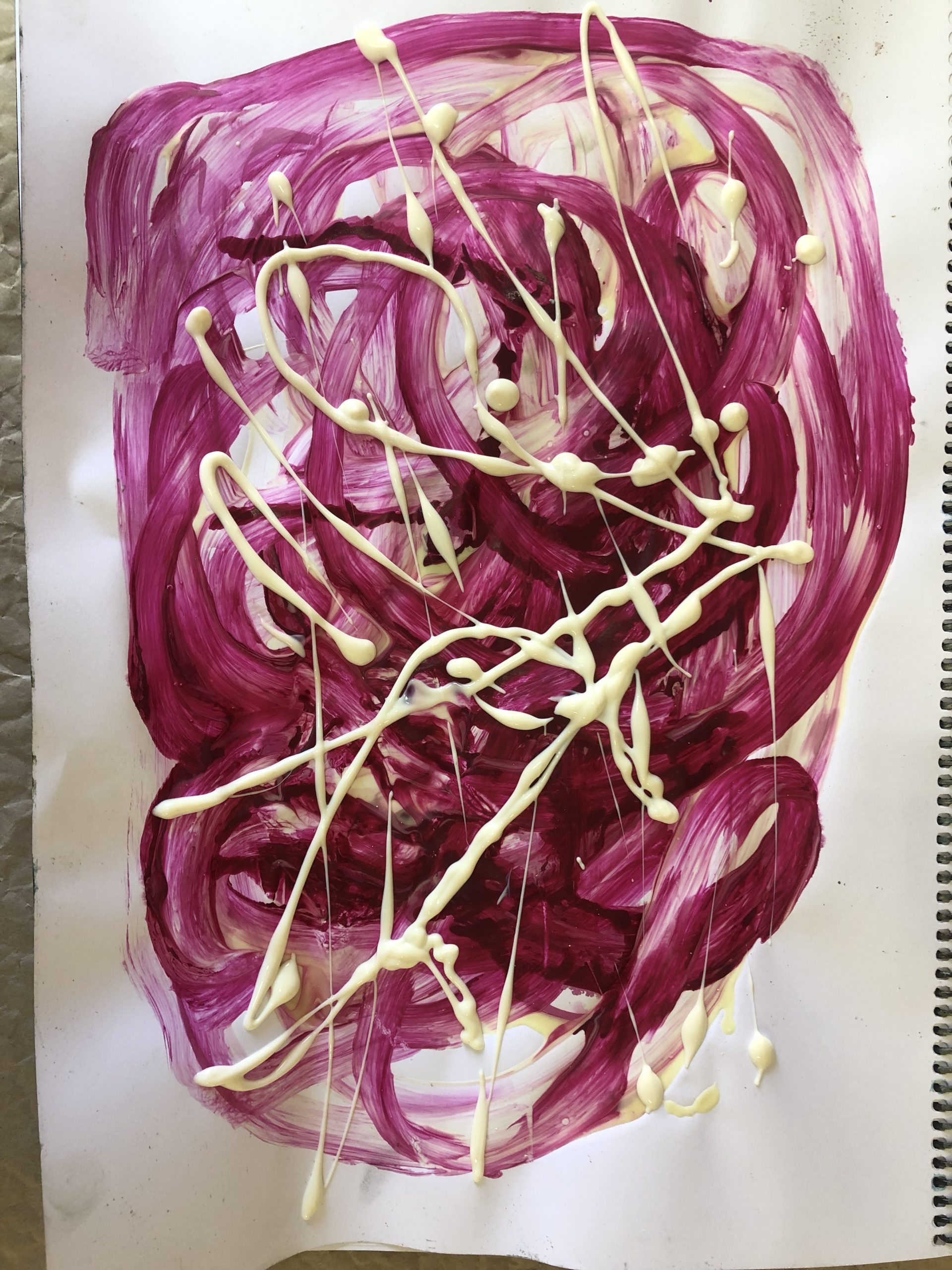

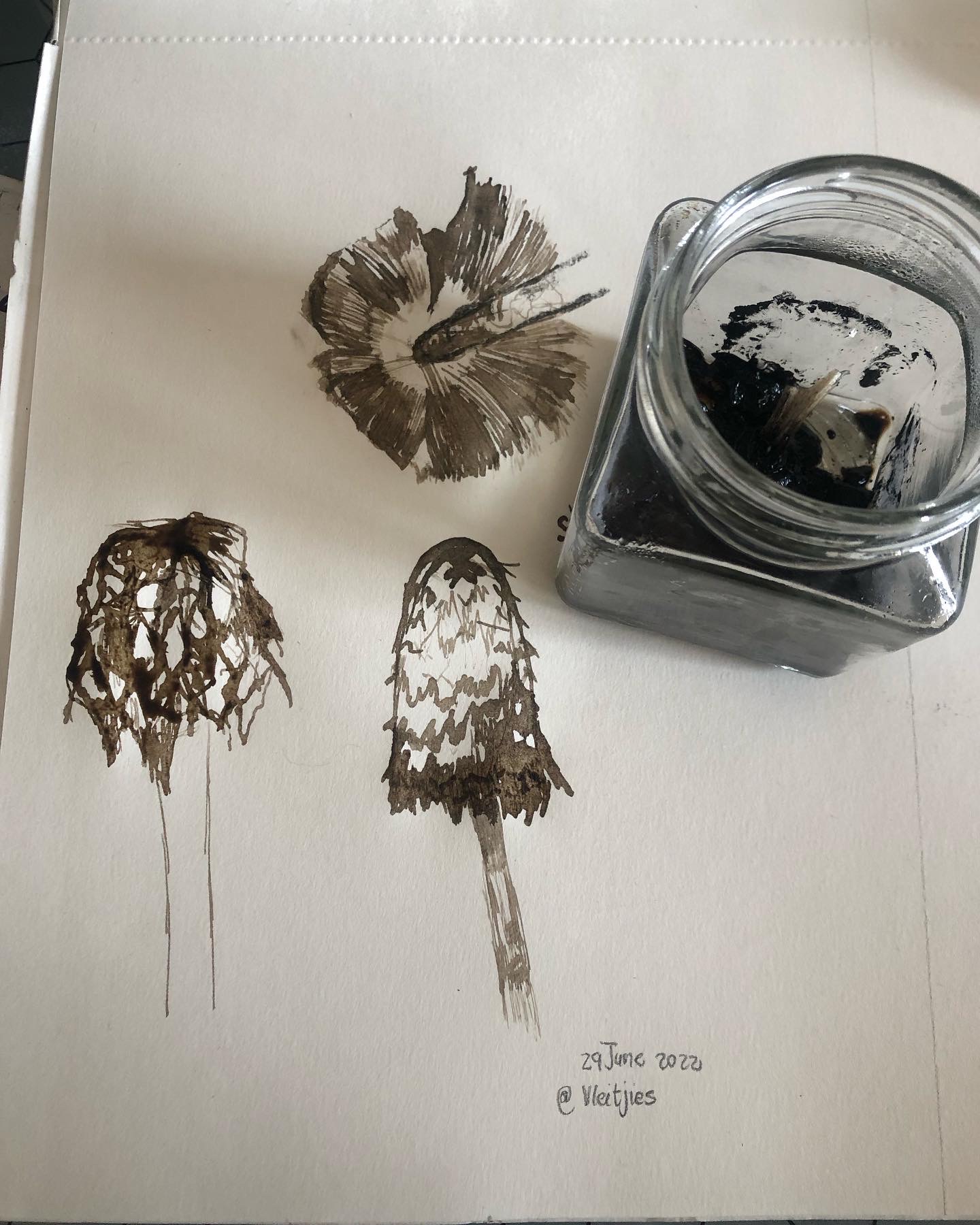

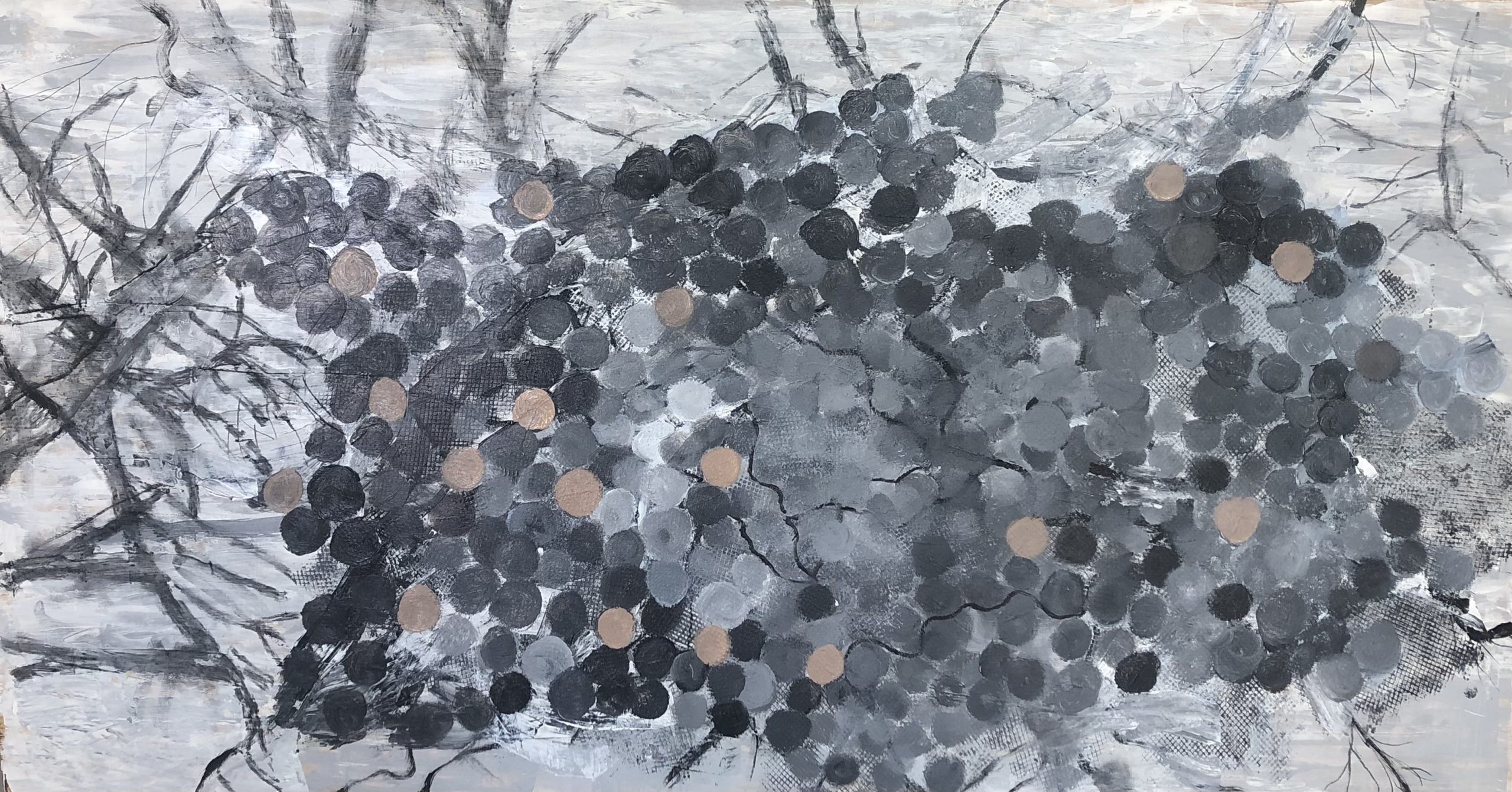

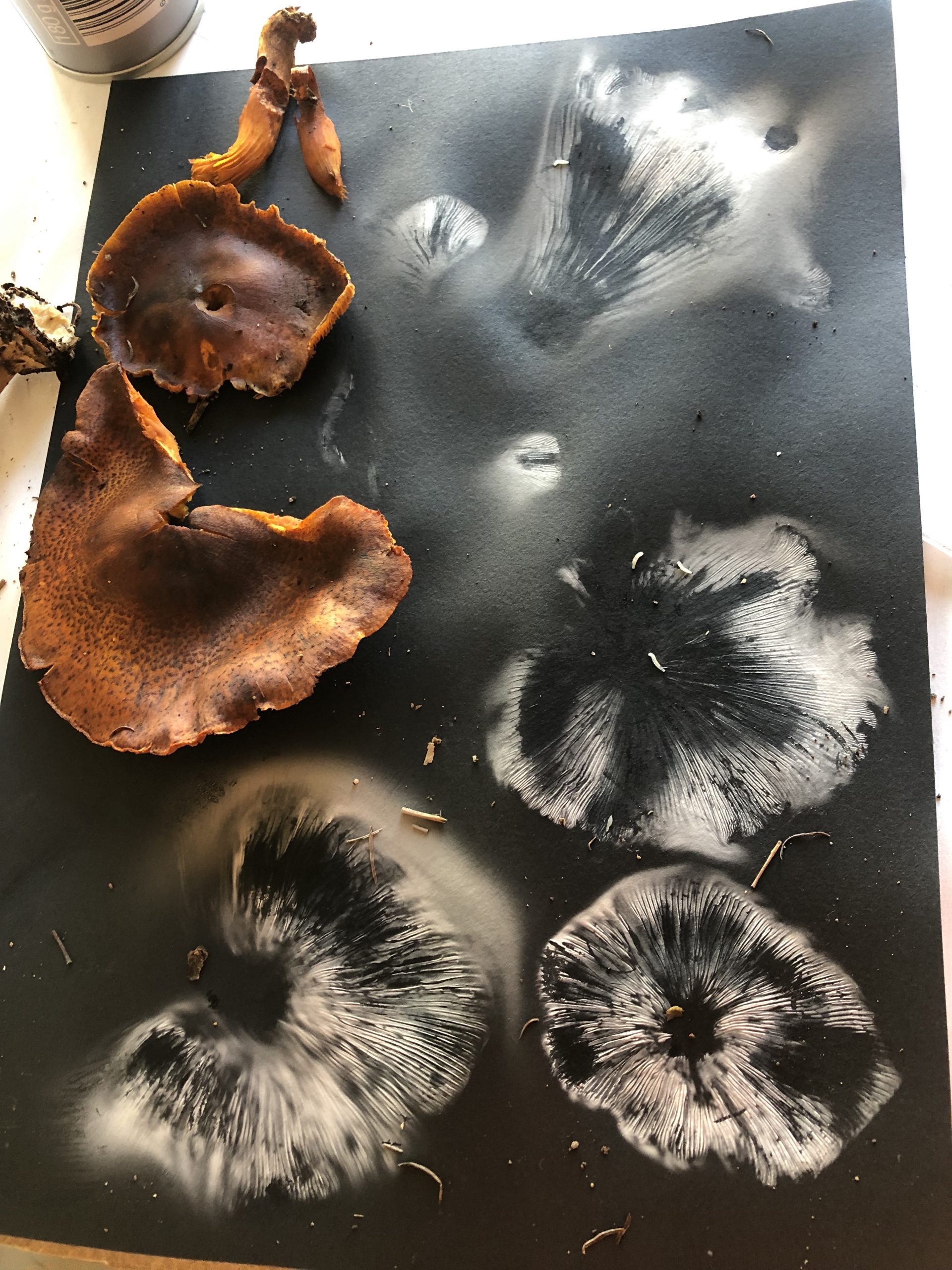

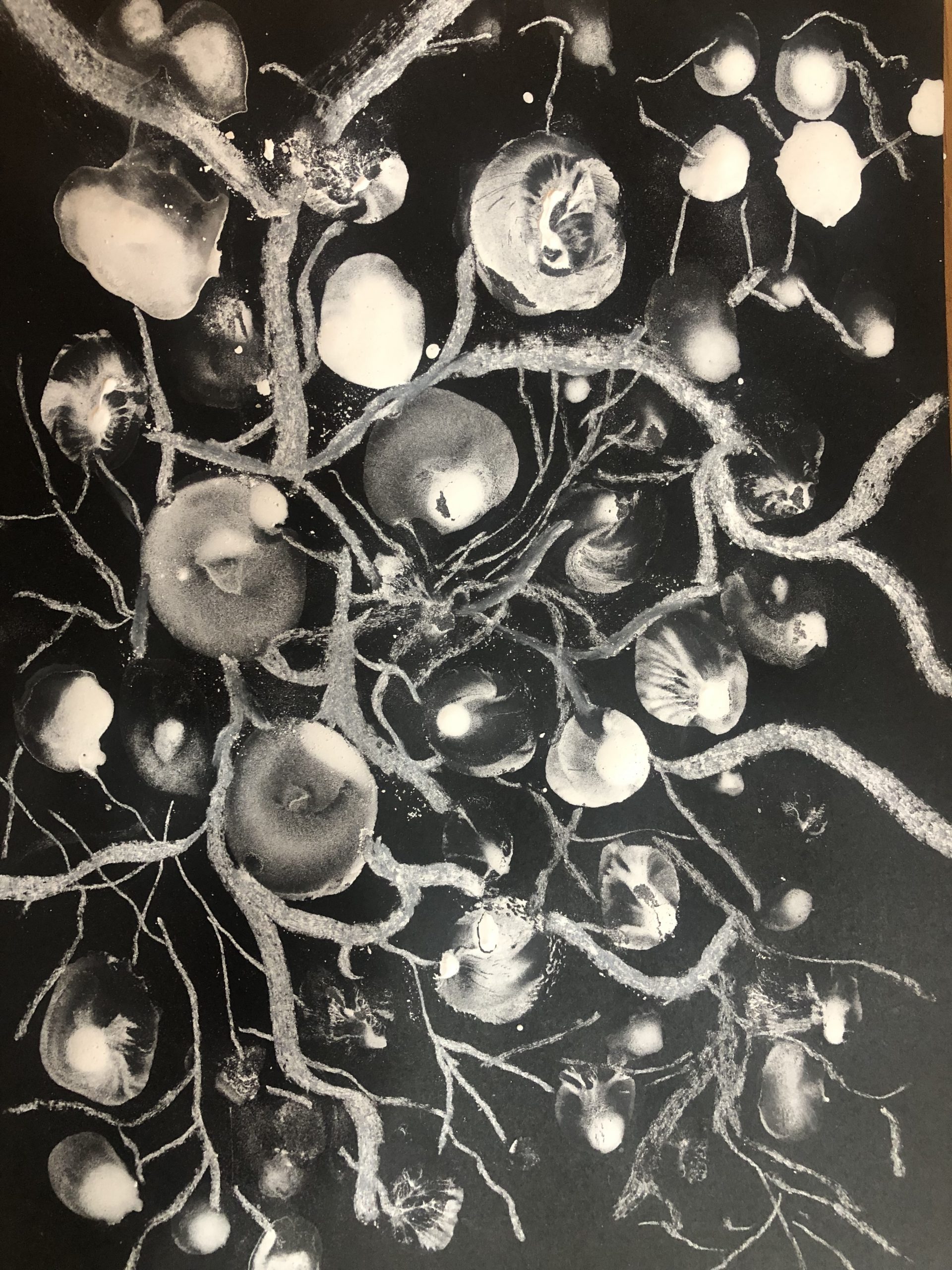

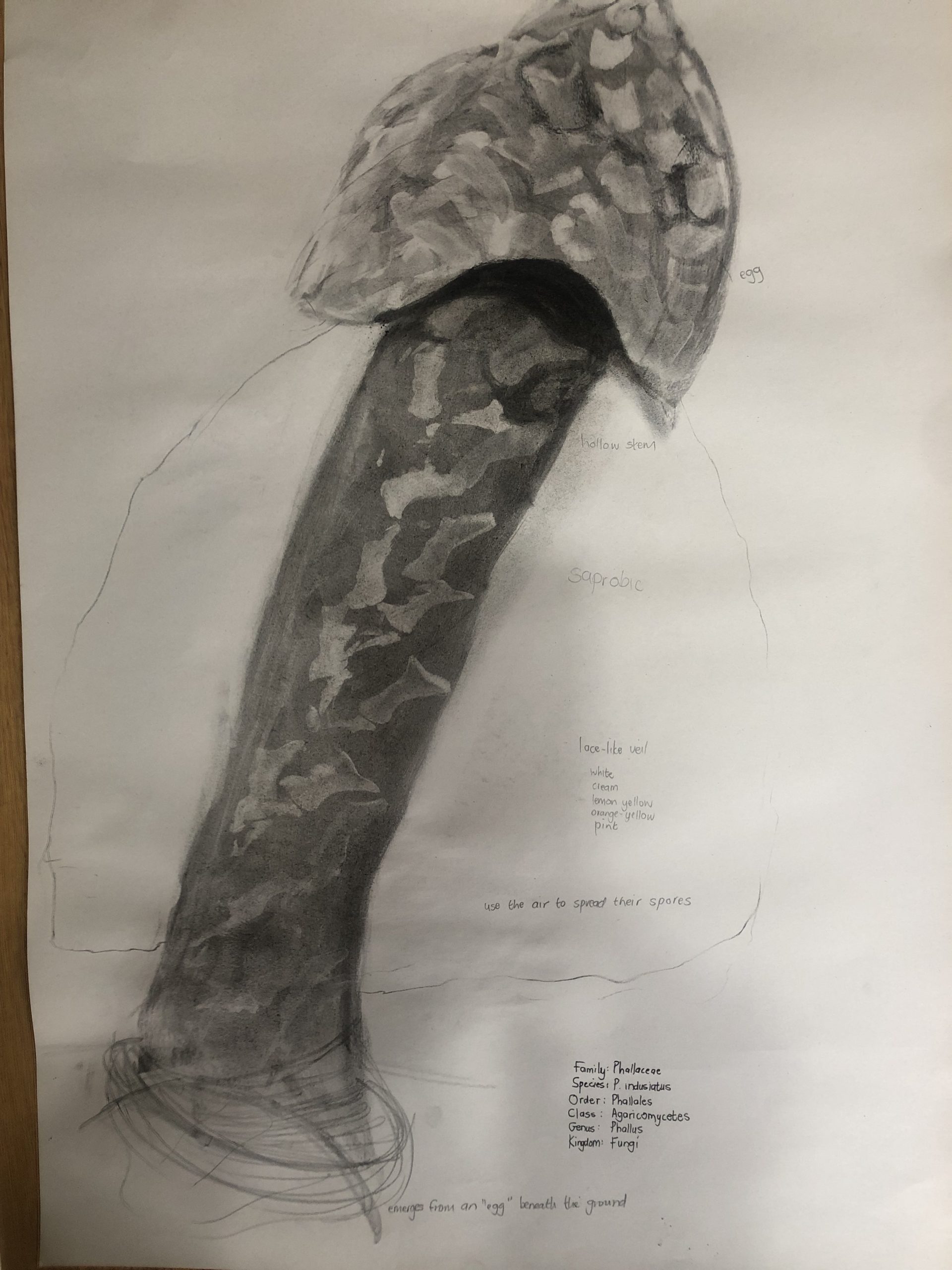

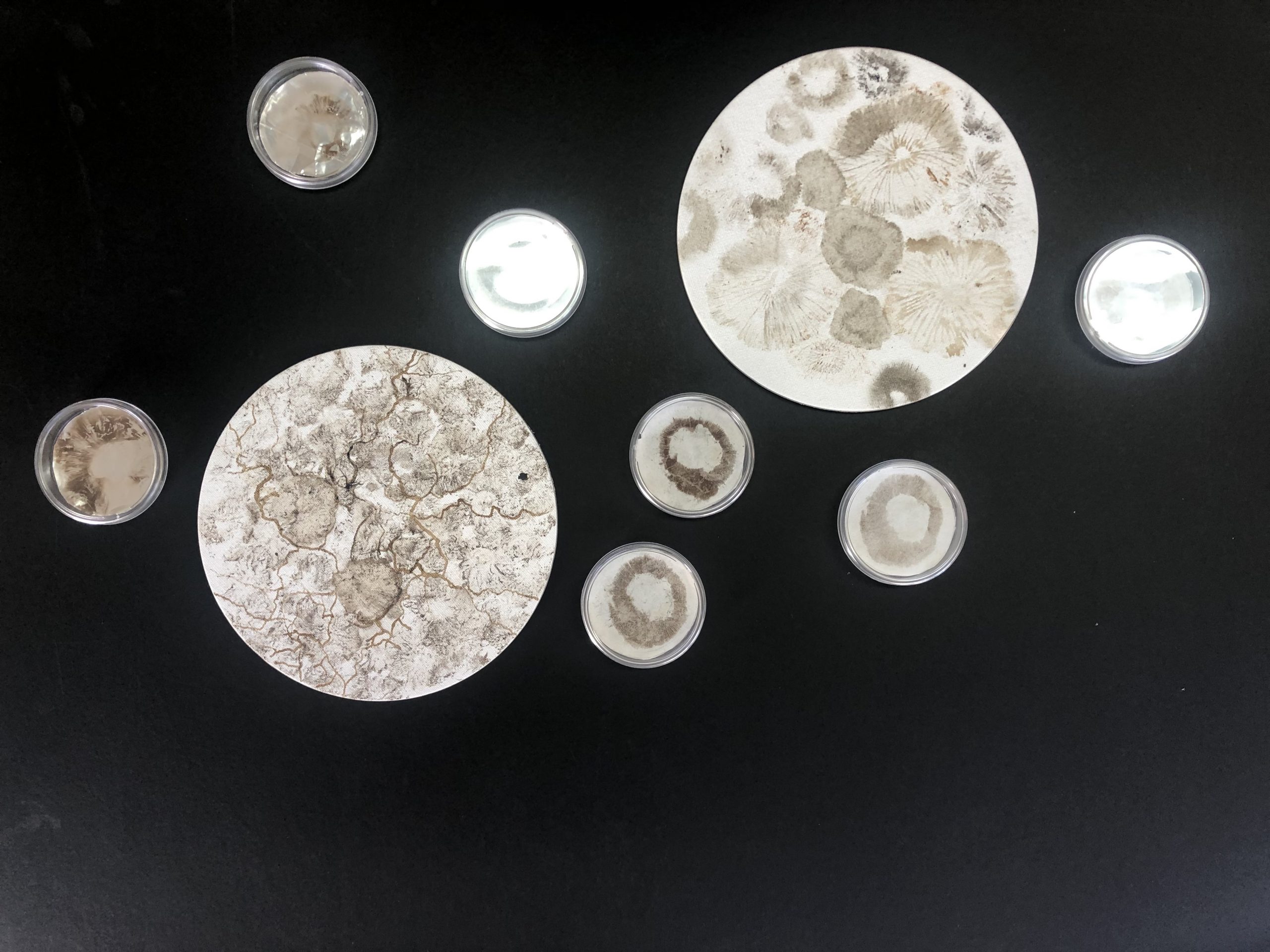

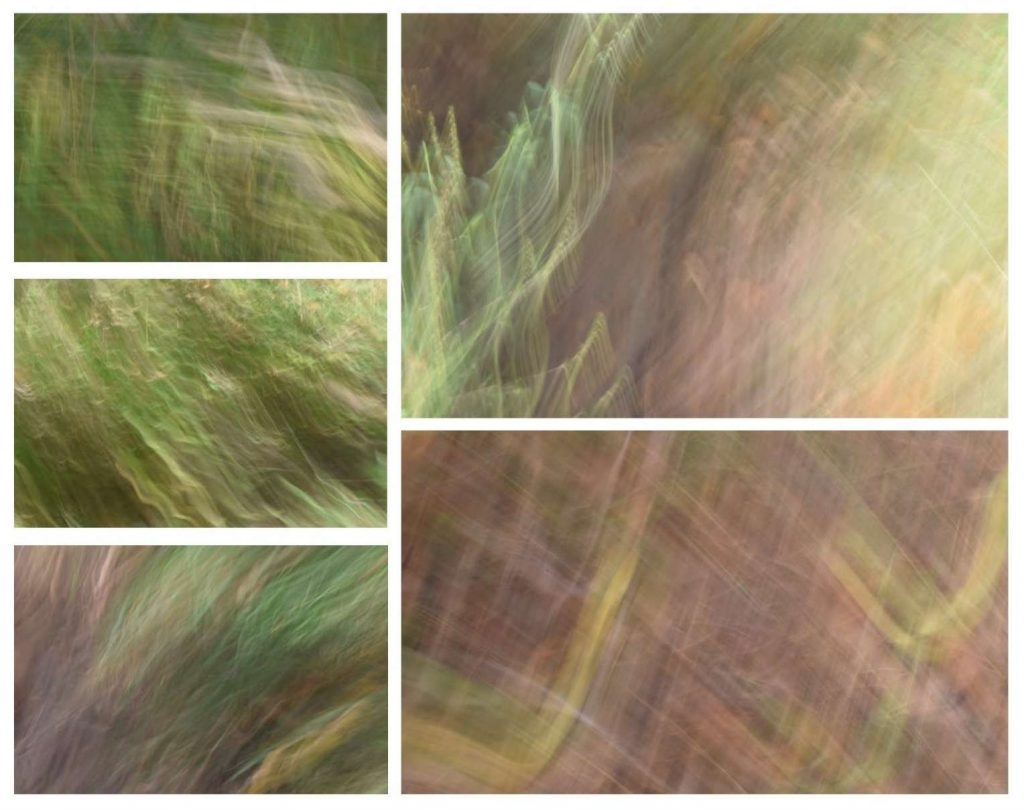

I did autonomous research on the Fungal Kingdom, and artists who work with Fungi. Growing and painting fungi as a material to work with have now became the biggest part of my practice. During this course I have worked with a range of materials in this course as the projects explored gesture, alternative painting tools, thinking whilst making, by considering movement and bodily actions led to using inks and action painting. I considered bigger brushes, ink, and different surfaces. I liked the texture of the Japanese/Chinese paper and Sumi brushes. The work about Still life and sculpture or 3 d work and exploring not only the pictorial space, but also the physical space around a work, made me consider other materials such as clay, foam, plastic, plaster of Paris, paper, wire, and rope. Working on a larger scale became a challenge I still need to do with confidence. The foam challenged me around issues of control and being soft when you start out. I had to plan ahead in terms of manipulating size and form. It reminds me of the throwing of paint as a gesture. I felt the pull between drawing, painting and making 3d objects, and my awareness grew around interaction and experience of materiality of paint.

in tutorial sessions my tutor encouraged me to hold onto my ideas, and explore and embrace my interests, as it is there that I came to find how to look at problems and that I have a tendency to work across and not stay too long with ideas. I do think it has to do with my need to show and make work to comply with a specific exercise or assignment. I do look forward to exploring and working more autonomously during the next level. I look back at this course as a journey with materiality and my own enjoyment of becoming more confident with my own creative mind and way of doing and exploring my world.

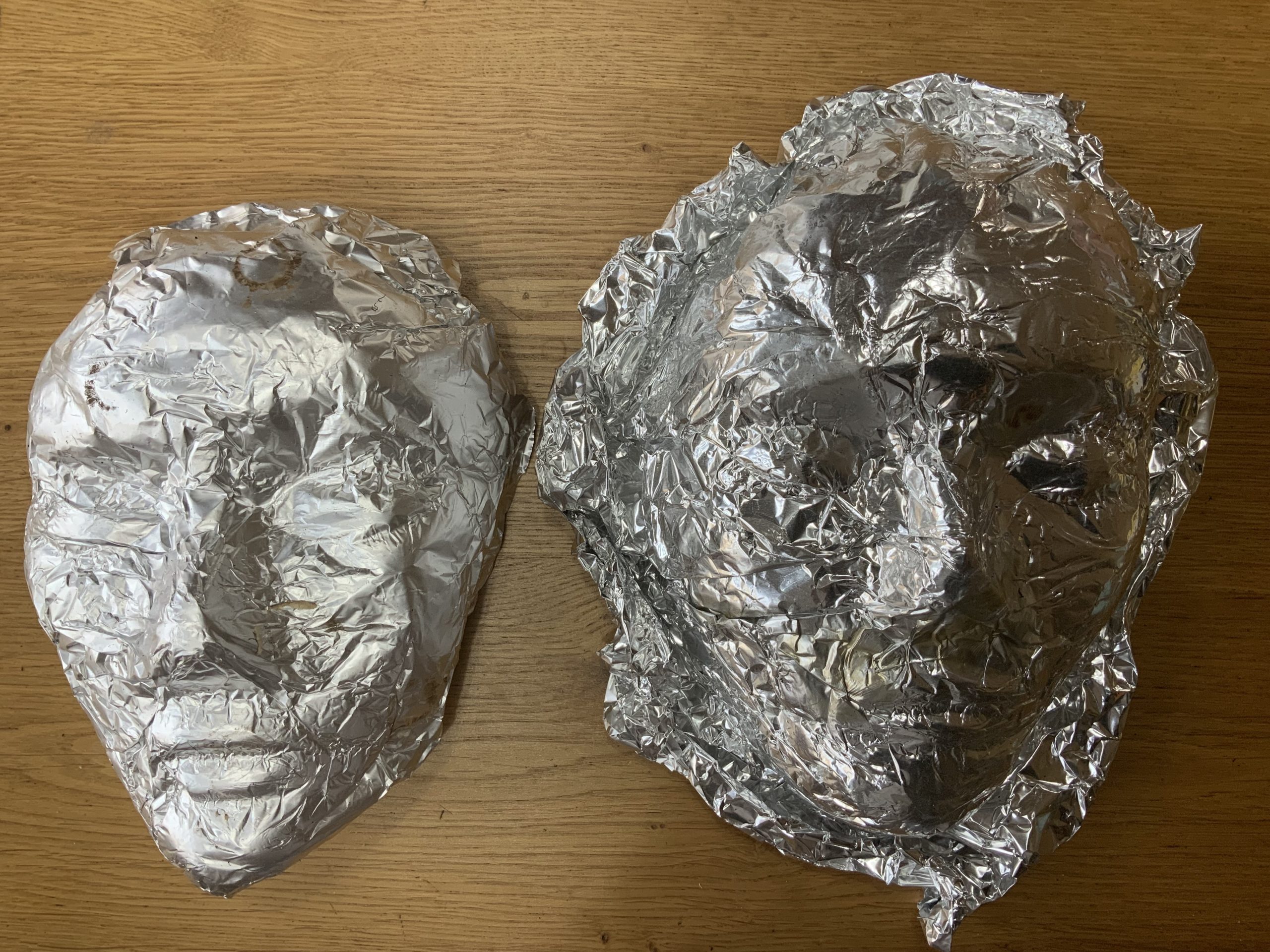

I thought to show some of my explorations as a way to how I responded to the course and my research in my parallel project. The pull between making a painting and just painting showed in 3d work I explored, but it also showed the forms which were taking over my mind as I was looking into the Fungal Kingdom.

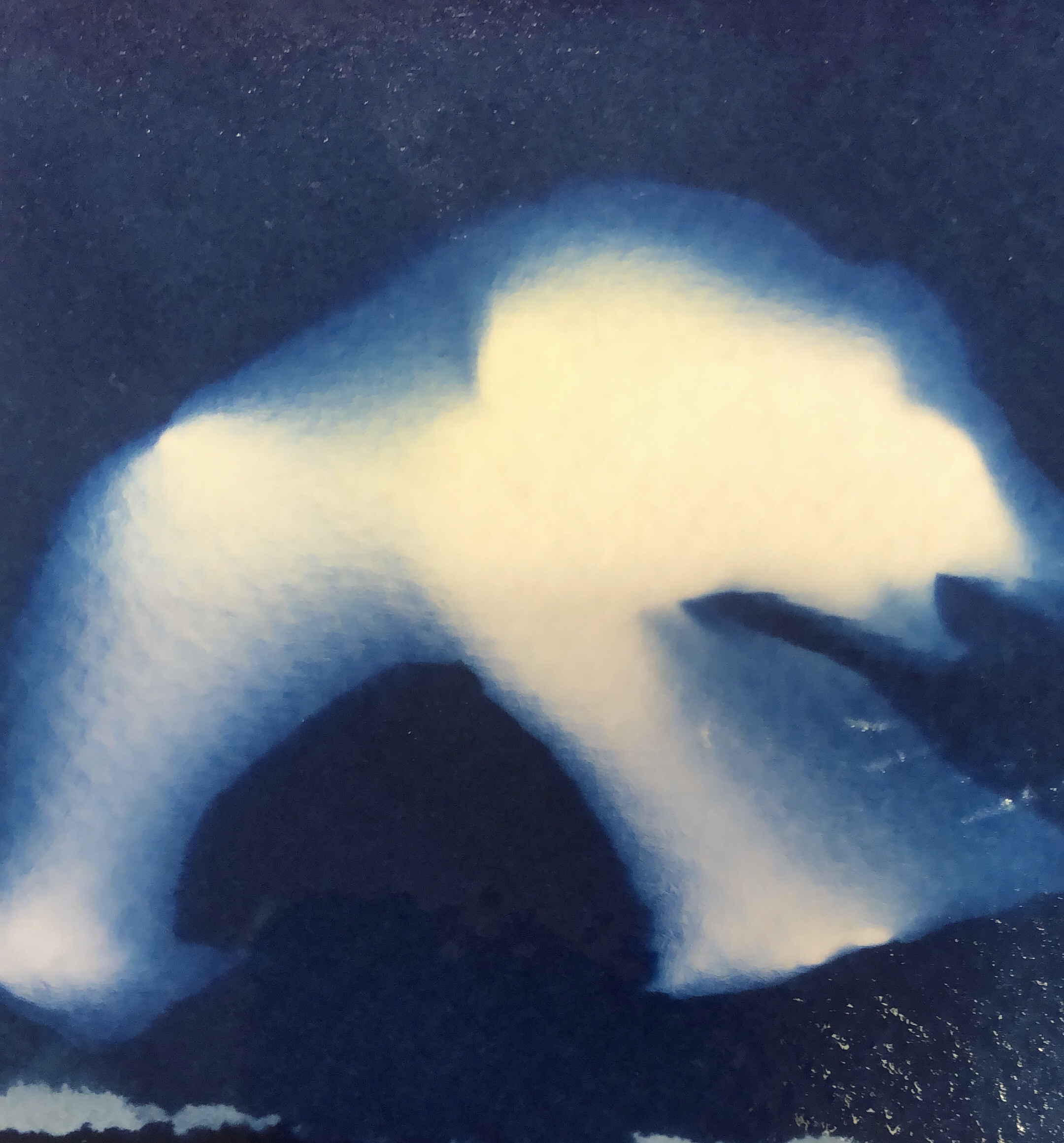

It seems that as my work now also includes working with a living organism, a form of documentation of my making and happening (outcomes not always controlled) became necessary. I have to write about my making in my learning blog, but my subject matter became denser and documenting became necessary. I used photography and videography as forms of documentation and shared this process on social media platforms (Instagram, Facebook, as well as Padlet and in Zoom meetings) with other students and in group work sessions. I look at this process as one way how my work expanded the boundaries of painting to include a reliable recording of the making, anticipation and sometimes unintentional observations with living material. I would like to use time-lapse in further explorations. I am not sure if I can claim that my documenting work is objective. Research of the fungi was mostly done through looking at visual images, and physical species, as well as reading about the type with regards to identifying form and appearance. I use an App to identify species of fungi and lichen. I cannot help but feel reminded of what Susan Sontag (UVC 1 and 2 reading/learning) wrote about a photograph as being the opposite of understanding and that it can be layered with meaning, it is mute – “which starts from not accepting the world as it looks”….”understanding is based on how it functions. …functioning takes place in time, and must be explained in time.”

I am keen to consider attending to the local and having a relationship with the living world. In discussions in tutorials with my tutor, an idea/advice that stood out for me was to ‘kick against the literality and find my way into the life force of the fungi. In that place or space, there could be so much materiality to explore – the cellular layers refer to human structure and this alliance or things we share with the fungal world. I would like viewers of my work to see (visually experience) how my ideas and thoughts developed through the exploration of different materials, techniques, and experimentation as a coherent presentation.

As I am writing this piece, aeroplane-driven spraying of the crops is happening, and here in the herb garden outside my studio, the collaboration work (Involution, 2022 Annette Holtkamp and Karen Stander) is in the process of being consumed and changed by fungi and other natural phenomena outside.

I live in a rural area, on a farm, and walking in nature is a regular embodied practice which complemented my interest in the Fungal Kingdom. On a farm one’s life (flow or rhythms) is generally indicated by time (day and night), the seasons, the lifecycles of the plants and animals being farmed with, and the weather. When one starts to look deeper into a connection with the landscape, I am always amazed at the quietness (stillness) of this place, compared to a visit to a town or a city, as well as the difference of importance placed on water and temperature (rainfall and snowfall) during our rainy season, which is winter. From foraging mushrooms and looking at lichen I became more connected to looking at place as:

- traces of temporality,

- the surface where things happen, namely the soil and its health,

- the difference in shapes and form of the studied object,

- the adaptability to change

- a becoming, it is dynamic,

- how weather as a phenomenon plays a huge role.

I would prefer to see the use of photos and video as documenting, as a form of optical language that happened in a creative experimental space between me as the artist and my materials.

Shelldrake wrote that we “shoehorn organisms into questionable categories all the time” and reminded us that a student of Aristotle, Theophrastus, wrote about truffles, but only to say what they are not. He wrote about them as having no root, no stem, no branch, no leaf, no flower, and no fruit. Somehow it seems that our Linnaean system of taxonomy does not cope with the Fungal Kingdom. So sensemaking through systems of classification is not the only way we understand Fungi, and surely could influence the bias which is mostly metaphors to describe this relationship, I have come upon. I also think the work of Cy Twombly and the way he approached ideas and make work, gave me more freedom to work across different ideas and media – exploration brought learning and new ideas of making and working with the fungi and lichen which I am making my work.

I became more interested in the work of Natasha Myers who looks at ideas of conspiracies or solidarity between artists and plants, and restoration. Where enchantment comes to the front. Myers suggested small gestures or aspirations stop destruction and regenerate. It leaves one with hope of altering the course of destruction and considering that it does not have to be destruction, we can reconfigure it, and one way is a relationship of restoration with the land. When thinking about collaboration, Annette and I, as collaborators in an OCA EU online group art exhibition, became aware that we would like to steer away from ideas of conflict and competition and prefer to use mutualistic relationships, which neatly fit our relationship with the Fungal Kingdom and ideas about involution.

I

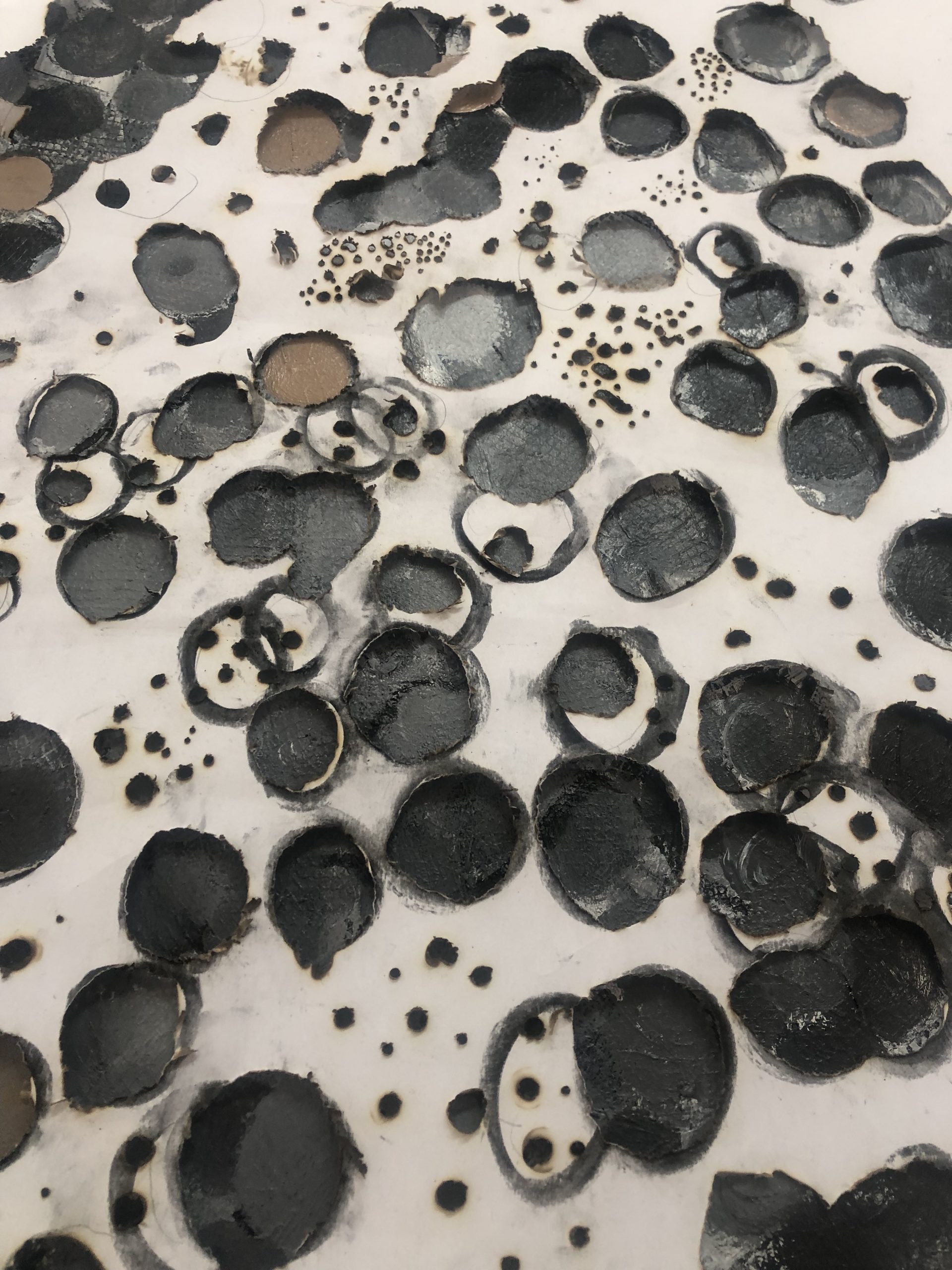

In my recent making (growing mushrooms to harvest the spores for creating 3d objects) the idea of care was considered. See image above. My work with fungi has a lot of unseen activities, routines where I make growing medium, take spores, innoculate a growing medium, and have to ensure the moist levels, temperature levels, or light/dark is in order. A while ago we went camping and I had to ask a friend to ‘babysit’ my mushrooms which have started to grow (pin).

The ongoing work, Involution, which is placed outside, asks for care. Here Annette and I want to use the potential of fungi to decompose our work. I need to keep it dark and moist and have to check on it regularly during the course of every day. Routines are used to ensure the protective layer stays in place. In order to ensure mycelium growth will happen – on windy and sunny days, the plastic sheet can lift or shift away from the work and not act as a protective layer.

This care is part of how my work can be created or come to being. In Matters of Care Maria Puig De La Bellacasa places care at the heart of how we might know, relate to and sustain the world. There is a radical openness to human and non-human others and concern for the excluded and marginal. To me, it became- a thinking-making process which favours continuous entanglement with the work of others.

I also came upon the work of Giuseppe Penone, when I listened to a lecture by Dr Giovanni Aloi, an art historian who currently lectures at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and Sotheby’s Institute of Art in New York, and London. (Acedemia.edu) As an Arte Provera artist, he looked at urbanization and realities after the Second World war in his country, Italy – he asks questions about nature and ecology and the dichotomy between nature and culture. I agree with his critique of a deliberate alienation between art history and nature. Aloi in his lecture looks at mythologies as an acknowledgement that non-human beings are interfaces to help the artist explain phenomena, in ways in which we try to understand the world. In Penone he saw how new mythologies can become personal, where the artist is present, and linked to the notions of seeing and touching. The privilege and tradition that sight as a convention (how we shape knowledge) are challenged by Penone. Did we become blind to nature in the West? Why do we claim superiority over it? Touching something becomes a confirmation, and an intimate and a less objective way to develop knowledge, seems to be what Penone is showing in his work.

Aloi shares a work where Penone used his fingerprint at the base of the work, which becomes a study of trees

The fingerprint of humans can be seen as anthropocentrism, so much engrained in this print – perception is hardwired in us, what we see, is seen by us. What we can say about the non human, is still said mostly by

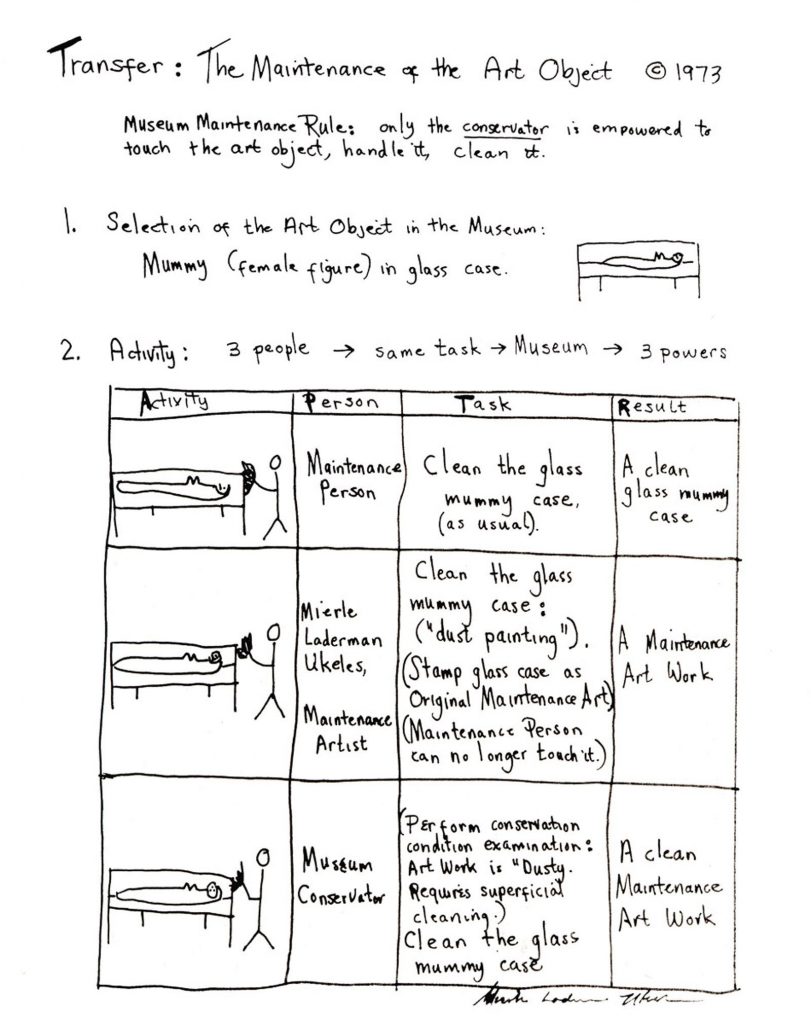

I am reminded of the work of artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whom I researched in UVC 2 and revised her work, Manifesto, 1969.

I wonder if this (my) care or maintenance can also be seen as a form of repetitive action. I am not a mushroom farmer, but in order to have mycelium and mushrooms for exploration of work and material of the fungi, I have to have a growing schedule. I am not close to a mushroom farmer or supplier of growth material and as the season is changing to summer I will not be able to forage mushrooms. I could make a list of these maintenance tasks my work involves and share it with my audience. I could consider the use of a questionnaire as interactive work between me and viewers.

Melissa J Graig in an exhibition statement writes about mushrooms that make people uneasy or squeamish. She reminds us that fungi are agents of change. On her website I found her writing so appropriate: “Some people have uneasy, squeamish thoughts when they look at fungus: it’s something surreptitious, uncontrollable; it lives hidden underground in familiar locales, ready to spring to life unexpectedly, and it often manifests itself as part of the demise of another organism.” (Melissa J Graig: About (S) Edition). The work called (S) Edition, 2010, consisted of 99 paper mache sculptures of books that appear to be growing out of the walls like mushrooms. The work consists of the cast and hand-shaped abaca, embellished with cotton rag; each copy is 14-18″ H x 15″ W x 16-18″ D.

The video work, Becoming a Sensor, by Natasha Myers and Ayelen Liberona, mostly explores movement, gesture, sound and text. (see image below)

Having read Specimen Days and Collect by Walt Whitman over the last year, I feel more aware of the importance of nature as a healer or nourisher, that is if we see in the way Whitman guides the reader in the art of seeing and so beautifully described in being with a tree. On 1 September 1876 he writes about The Lessons of a tree, his favourite, a yellow poplar tree: “How strong, vital, enduring! how dumbly eloquent! What suggestions of imperturbability and being, as against the human trait of mere seeming. Then the qualities, almost emotional, palpably artistic, heroic, of a tree; so innocent and harmless, yet so savage. It is, yet says nothing.” (2014:101)

I ask myself how my own artmaking gives meaning to mentioned ideas.

Can I add a role to myself as a conduit?

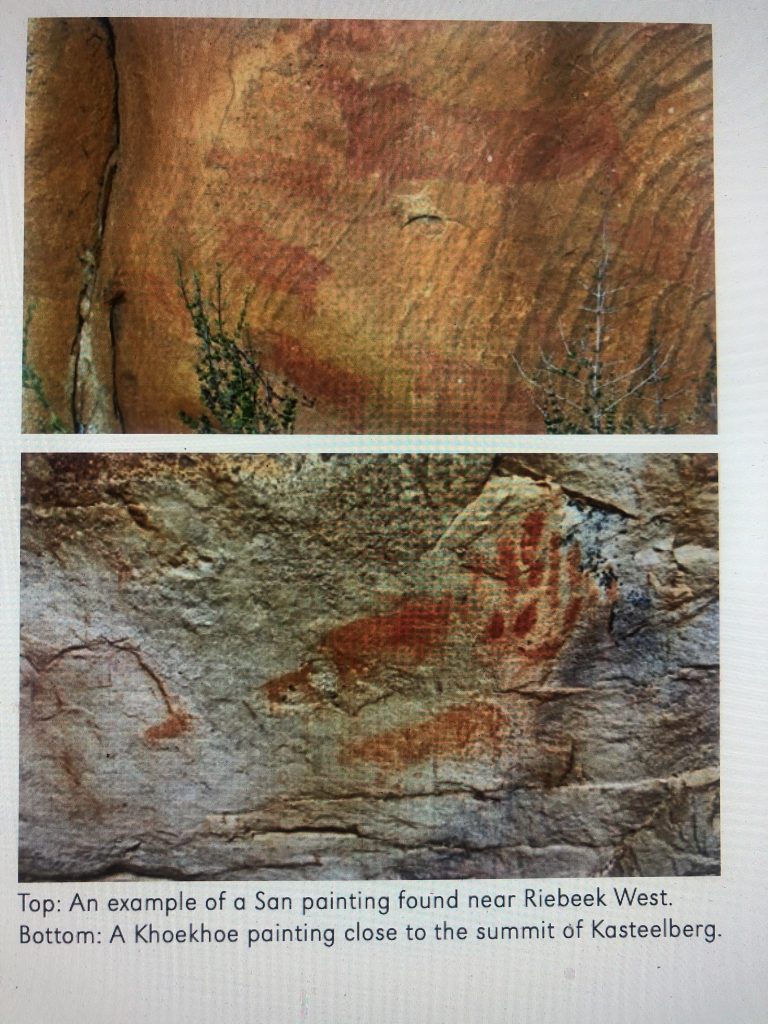

My place lies between two mountains – the Riebeek Valley. The one mountain, called Kasteelberg, rises 966m above sea level and is described as a fynbos paradise. The town lies at its foot and I live on a farm around 8km from the foot of Kasteelberg. ( I see the mountain from my studio) Archaeological evidence suggests that people of earlier to later Stone Ages lived in this area, today called the Riebeek Valley. The San were the original human occupants and known by various names such as Sonqua. Not far from where I live, there is a farm called, Sonquasdrift. Local tribes who lived in the area before the colonisation by the V.O.C in early 1652, seem to be Strandloper, Khoisan, and Sanqua tribes, called Hottentots and or Bushmen by the Dutch colonials. (Goodwin, A J H, South African JSTOR Journal article from the Archaeological Society, published in the South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol.7 No. 25 (March 1952) pp 2-53. It seems that these tribes mostly spoke Korana languages and were pastoral communities or tribes that lived mostly nomadic as they followed the best grazing for their livestock (seasonal). I read in this document that the Soaqua bushmen were regularly accused of stealing cattle, by the J van Riebeeck settlers. The Sonaqua tribe did not own cattle and was seen as a wild nation without huts, armed with assegais, bows and arrows – they were hunters and lived off the veld. The important thing to remember is the knowledge that came with this way of living.

In 1661 Pieter van Meerhof, a Danish surgeon and explorer, who joined the Cape Companje, named Kasteelberg after pitching camp on the 4th of February of that year, whilst on his way with a group to explore the Northern parts of the Cape. The valley obviously got its name from Jan van Riebeeck, the first colonial leader, who claimed Cape Town harbour area for the Dutch V.O.C. In 1664 Van Meerhof married a Hottentot woman, Eva Krotoa, (also known as “Eva the Hottentot”) (circa 1642-74) She was the first African to marry a white colonialist in a Christian ceremony. (Pieter van Meerhof was from Copenhagen, Denmark. He arrived at the Cape on the ship Princess van Royael.) Today Meerhof is a famous wine farm in our valley. By 1704 a number of farms were granted Goedgedacht, Kloovenburg, Allesverloren and Vleesbank, these are still existing in the area. Agriculture concentrated on wheat, and later sheep, viticulture, soft fruits and olives have been added.

The Riebeek Valley suffered the regime of apartheid and forced removals happened in 1965 of non-white people living in a part of Riebeek Kasteel called Oukloof.

The hurt stays in the memory of many families. It is about place and what we connect with it, our experience (memories) and the history of place. I am trying to find the place where I am sitting between these histories, and it reminds me of my interactions and learning from mushrooms.

Through mushroom foraging, mushroom farming and spore printmaking, I became more aware of:

I wonder how climate change will affect the Fungal Kingdom and our interaction with it.

List of Illustrations

Fig. 1

Bibliography

Whitman, Walt, 2014 Specimen Days and Collect, Melville House Brooklyn, NY (p101)

Evans, Meredith, 2020. Becoming Sensor in the Planthroposcene: An Interview with Natasha Myers https://culanth.org/fieldsights/becoming-sensor-an-interview-with-natasha-myers ( accessed on 15/09/2022)