General comments on the work below.

In this part of my studies, when I started the reading for Research Point 2, I decided to first continue with the exercises of the Topic Experience and Authenticity and then come back and fill in the details and start writing them. I did the same with Research Point 3 and 4. I find that I was better informed around the Topics of discussion. I do hope that my tutor will agree with my method.

RESEARCH POINT 1

Use the links below, then continue your research of the following works: Richard Mosse, Incoming, 2017 and Helen Cammock, Changing Room, 2015.

In the next few paragraphs I will do the following:

- I will describe the two works

- I will compare them in terms of what I think their strengths and shortcomings are.

- I will critically consider if everyone have the same right to tell a story and to respond to it?

- I will also question if some voices are more or less valid and for whom?

Mosse, R. (2017) ‘Incoming’ In: Barbican.org.uk [online] At: https://www.barbican.org.uk/richard-mosse-incoming

DESCRIPTION of Incoming, 2017

It is a 52 minute, multi screen video installation of footage of migration of people over time and from different locations en route to Europe, EU countries. The footage shows images and deals with concerns of the growing humanitarian crisis of immigrants who fled their home countries and in this process become refugees (fleeing from prosecution, war, starvation, drought and other affects of global warming.

To make this work the artist used a custom design military grade thermal imaging camera, made in Great Britain, in the recordings. The camera equipment is part of classified weapons as it is used by the military for surveillance. The camera weighs 23kg, is controlled with laptop technology, high technology interphase software, need batteries and used on a steady cam. The gear weighs a total of 80kg. The camera uses thermal imaging and can detect the human body from 30.3 km, day or night

The images are slowed down in the film production – shoots at 60 frames a second, they slowed the frame rate to 24 frames per second, could engage with people’s gestures – potential for intimate portraiture, invasive…see intent of gestures. He uses the still frames to compose his photo images

STRENGTHS AND SHORTCOMINGS

- The artist always starts with the medium, which is photographic forms and media.

- His art has close relations to journalism and integrates documentary work, as he tries to relate to world affairs like displacement and conflict, the humanitarian disasters playing out, by using photography to reflect on this.

- He is a collaborative artist and would work with film directors, musicians, humanitarian activists, etc.

- He sees himself in the space between documentary photography and contemporary art, because he challenges the conventions of documentary journalism/photography.,as being truthful, objective and authentic, also to find ultimate and or better approaches to these ‘stories’.

- One wonders about a tension between fiction and reality: could say that the camera is used at the expense of the subjects, but I think the heat camera actually protect the subject, as they are impersonalised by the heat technology used.

- It also makes you think about how governments/power make use of this technology in the name of safety/security, but personal privacy becomes an issue. Just consider the focus on AI technologies for facial recognition and surveillance, and further developments which happens through machine learning, such as identifying people by the way they walk and trying to read emotions.

- There is the question of ethics behind things – he understood the power of this product and its technology application it was designed for, but could coop and subvert the technology by using it for filming and photographs to show things that would normally go unseen, but could give wider meaning to the situation of fleeing refugees. The product was thus not designed for story telling or to be used aesthetically. I do think he changed its use.

- He challenges his viewers with questions, rather than to provide answers

- The work touch upon the ambiguity of this subject

- He used the technology against itself to create a humanist art form, the camera is blind to skin colour

- Contemporary art/photography is developing into reportage photography—documentaries, but do not want to aestheticise it

- I remember an ad slogan Sontag refers to in Regarding the Pain of others, ” the weight of words, the shock of photos” (Sontag, 2003, p 20)

- It forces a viewer to deal with what is being seen/viewed/experienced – one is in a difficult space, uneasy sense of their own complicity (being there/here)

- very visceral, emotive, even aggressive

- limitation of doc photography – (pink kleure van Kodac chrome…film,vir oorlog gemaak – reveal the hidden)

- he showed photo images in digital print on metallic paper as well as videography which was shown as a 3-channel film, with footage of the movements of refugees, like arriving on a boat in the Mediterranean

- landscapes were scanned from high elevations and these footages were used to make composite thermal panoramas

- confront the ways our governments responds to this, and how they regard the refugee

- the bare life of stateless peopleWe live in a new era of closed borders, halted migration, and widespread fear of contagion. Refugee camps within Europe, such as Moria on Lesbos Island in Greece, have been quarantined and the gates locked, becoming, in essence, open air prisons teeming with asylum seekers. In this context, Richard Mosse’s immersive video artwork, Incoming (2017), is as relevant as ever.

- While EU nations discuss the pros and cons of introducing ‘immunity passports’, Giorgio Agamben’s idea of ‘bare life’ is foregrounded. Immunity passports would be another instance of biopolitics, the stripping of our essential human rights by the nation-state during a state of emergency caused by the coronavirus pandemic. Agamben’s ideas were a source of inspiration to Mosse while he made Incoming.

This talk took place on 20 February 2017 when Richard Mosse’s Incoming was on display in The Curve.

Description of Changing Room, 2017

Cammock, H (2017) ‘Changing Room’ In: Youtube.com 05.01.17 [online] At:https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDmNiRDSOdwYSQ7HZo3MX8w. (This video was found on Vimeo and is not accessible on above link from the study material.)

It is a combination of words and images where the artist is telling a fragmented story, which sounds like that of her own upbringing. The narrative is about remembering things said of experiences, dealing with emotions of regret, shame and anger, and memories of being a child in a mixed married relationship, and having an ambitious, but frustrated father who was a ceramic artist as well as a magistrate . She talks about her own memories of him, ideas as well as others, mainly it seems, that of her dad, who was a Black man. The story moves whilst images of an interior of a room is shown, mostly carved or made pottery/clay objects. She asks difficult questions on being a person in a minority group, the pain of rejection, being subverted to racism and dealing with it. I am deeply touched by questions such as : “How is worth formed, and how is it sustained? ” She is talking about somebody else, but she is not excluding herself – she shares her own questions/interpretations. The ceramic objects she starts with, an Okapi, is an endangered mammal native to the northeast of the DRC in Central Africa – it looks like a zebra. The white polar bear(?) also seems like a metaphor, or is it incidental? I later read that her dad was of Caribbean descent. I also read that she shot this film in her dad’s house, shortly before he left for a care facility. Her words about being well educated, but because being black, the prejudice and hurt is painful to hear. She shows empathy for her dad’s hurtful childhood and upbringing in a segregated society, which was not always visible – but institutionalised as they experienced it.

In an interview with Chris Fite-Wassilak, a writer and critic (Frieze,2018) she talks about her interest in lament: “…I am drawn to the poetry and music of lament” She sees this as being a personal, generational and historical lineage of sadness, longing and loss as a black woman. She feels it is important, although it does not belong to her own experience, but that it is “something that is often ignored or undermined as part of world histories; and of course it is present most visibly in conflict, displacement and refugee stories. These are absolutely universal, historical and contemporary cycles of damage and loss; but it is also a part of the everyday for everyone at certain moments, or as prolonged or lifelong conditions. For certain communities these experiences mark their continued existence, through complex tapestries of personal, psychological and social understandings. I am interested in exposing this, unpicking this, asking people to witness this. The cycles and manifestations of it are part of our continued ‘unseeing’ of particular experiences and I think this is very damaging for a collective psyche, and affects certain communities more deeply and widely than others. But lament is constant – it never leaves the world.” (Frieze)

STRENGHTS AND SHORTCOMINGS

- Her practice in the piece I viewed is mostly about what she has experienced, through own personal experience about that what feels she has knowledge of.

- Her earlier work was mostly autobiographical, in the sense that it was about her own experiences, her later works are more global and speak to a wider experience – example of work with women in Northern Ireland and Italy.

- She would start with research and use achivial materials in her work

- She is a multi-disciplinary artist who incorporates video, spoken word, lately singing into her powerful projects.

- She uses her own body – voice in this work, reading from her own script, but also using other texts and ideas form other people, translating into her body of work.

- She also uses the motif of song and music to find meaning in language.

- The work viewed/listened to, has no continuing narrative, meaning you can come in and out of the work at any time, there is no real beginning. (I am reminded of having seen many video installations with similar experience)

- The work create empathy and focus mostly on feminist issues in different parts of the world, it speaks to a wide audience

- I relate well with her views on her first work, that of firstly working asa social worker and the search for empowerment in the work. I was also a social worker. She feels she does something with the experiences of people as she transforms stories into art.

COMPARING

Both artists use film and photography as a medium to communicate very deep societal and political issues. Both their fathers were ceramic artists and they both grew up with parents who one would not say was the ‘normal’ type – I do think both these artists have experiences of being judged as different during their childhood, which made the empathic towards people with similar experiences. (My own idea as a young person to become a social worker or lawyer, had much to do with inequality in our society and my idea of being an ’empathic facilitator’ to clients) In their methods they use the medium of film different, one uses the medium to document other peoples lives, without them knowing/surveying, and the other share stories and histories which comes from a personal place of shared pain and experience of loss. Ms Cammock uses text and performance in her works as well.

QUESTIONS ARISING

One could ask questions about objectivity and truth in this difference around the stories/narrative in their work. To consider the one more true than the other is a matter of interpretation of what you see/view, versus what you see and hear about their subject these artists are showing/performing. One can empathise with the subjects, without knowing who they are in these ‘narratives’. Both these artists engage with their viewers by leaving them with questions. They focus on silenced voices and the hidden human history/experience which follows many times, due to political presence in our culture. With regards to audience I also think the works can be seen as signs of political and social shortcomings in society.

A question that stays with me after this research and reading is how histories of people are moving in and out of our vision, sometimes being forgotten, ignored. Both these artist brings this to the foreground – one cannot ignore the role of politics of the day. The pain that they portrait to make the viewer wonder if it can ever stop – will justice ever prevail? One could view these works stirring emotions of sadness and pain, but I think one also become aware of human strength and resilience, not to loose hope or to action change. The CNN effect could be used by these artists as activists – where the broadcast or publication of powerful images can force governments to act.

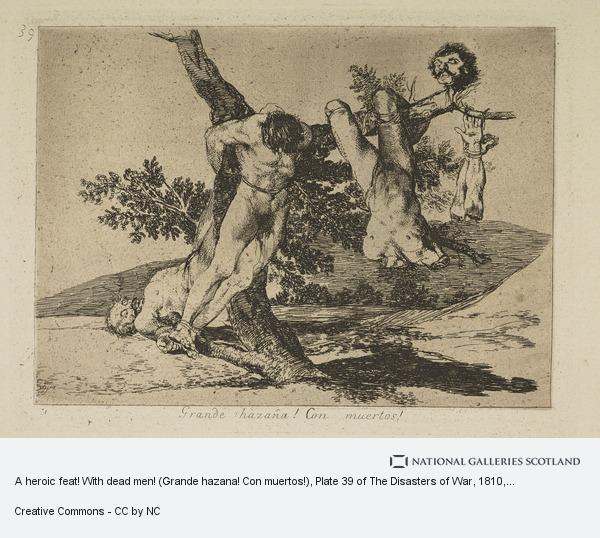

I am reminded of works by painters that addressed war, Picasso in Geurnica,(1937) who was anti-war, never took part in the war (most probably non political at that stage of his life) and the works of Goya, The Disasters of War. Sontag wrote that this was the first war ever to be ‘witnessed’ as in covered by journalists and professional photographers (Sontag, 2003:18). Goya’s series of etches deal with conflict and its carnage during the 1808 civilian uprising against the French and it is not easy to look at. They deal with their own experience of seeing horrific violence and communicating about that experience. (without any of the glory or picturesqueness (aesthetician) which has also been used in propaganda by government/politics.)

Again the question arise in my mind: do artists have to explain their work?

There are different opinions/interpretations about these works as well. Could one look at the work of Goya and Picasso’s Guernica, and compare it with the works as discussed above, by comparing who and what the artists was trying to represent as they all live (were living) in a particular political order which motivated them in them trying to deal (as a form of expression)) with their disillusionment about what they saw happening to people.

Should one see it as a form of expressive realism?

I feel these works are visceral; they make viewers uncomfortable and I am reminded about Sontag and what art should do. But I am also reminded by her in On Photography (1977) that after repeated exposure to images, the images become less real. She questions this again in Regarding the Pain of Others (Sontag 2003: 94-101) when she talks about television which created further banality about our exposure to wars, crime, evil deeds and horror of daily life, and considers erosion of a sense of reality – that we life in a ‘society of spectacle”. Here one has to consider the role of the media, channels like CNN. Sontag discuss Sarajavo and what stays with me is her words: ” most of the experienced journalists who reported from Sarajevo were not neutral. And the Serajevans did want their plight to be recorder in photographs: victims are interested in the representation of their own sufferings. But they want the suffering to be seen as unique.” She refers to a photojournalist’s exhibition that was held in the besieged city where he placed photographs he had taken in Somalia a few years earlier as well as his images from Sarajevo – it was not received very well. It seems that audiences care easier when they can identify with what they are shown.

In a conversation with Picasso, as recorded by Jerome Seckler in 1945 (Theories of Modern Art: 487-489) Picasso explains that Guernica is “…the definite expression and solution of a problem and that is why I used symbolism……..I make a painting for the painting……I don’t think of trying to get any particular meaning across. There is no deliberate sense of propaganda in my painting.” I am comfortable with understanding this as expressing experience, without ideas which are seeking to transcend it to political or other theoretical ideas.

It seems suffering and disaster always capture media attention. We as viewer need to consider moral imperatives to tell the truth and critical look as sensationalism and degrading of human dignity. I do think in that way stories with images are sometimes more effective, than images or real time video footage. I do believe in both instances one should value the work of these artists in term of whether it produced positive outcomes. Sontag (Sontag 2003:105) writes that that images which offers reality at a distance, like the suffering of others, is considered to be morally wrong, but suggests that it could be telling us something of how the mind functions when considering moral questions and how we want to escape those realities. “The images say: This is what human beings are capable of doing – may volunteer to do, enthusiastically, self-righteously. Don’t forget.” (Sontag 2003:102) I am reminded of art used as propaganda or against the regime (weapon). Below is an image of the work of artist Martha Rosler:

In the case of the two artists work I dealt with in the question, their subject is about people whom they are giving a voice with a new/different and very direct art medium, that of voice and camera. One can ask if they are ‘over projecting’ the subjects..are they becoming objects? I feel that these works both show reactionary content which I understand in this situation as being a ‘valid’ experience. Distortion came into my thoughts, both as a method of using it in art and to hide truth in general…..Sontag wrote about ideas that if one should say a photo demeans, then the assumption is that paintings distort in the opposite way, by making things grandiose. I should agree that both these works showed fragments of what happened to the subjects/people living in this real world we all share and try to make sense of. As viewers we do not have access to all the information, should we think about what was left out and possibly why, as well? Who was the real spectator/viewer in these works, and I ask that as I think about how anything can become art, and that anything that happens can be photographed or filmed.

In my own country we are dealing with histories of marginalised indigenous people, which are now being rewritten, recorded/archived about. Black artists, like politicians and activists for human rights, are putting these histories into their work as a way to deal with its effects on society, their own lives and that of other. And we still dream of being a Rainbow Nation.

In a project I started on Rhino killings/poachings for rhino horn, I have been looking at conservational, socio economic and cultural issues in Africa in my research to continue with this project. I have to look at the role of history, such as colonialism and how it made certain histories ‘disappear’ and ignored when it comes to wildlife and consumption of wildlife. I have been confronted with a colonial history of excessive hunting of wildlife in Africa (hunting biographies in the public domain of written stories by Selous, Cummings and Harisson, through to epic novels like Jock of the Bushveld, or the romanticized Karen Blixen stories about her life in Kenya. (evenHollywood caught up on it) and in many ways obscuring or romanticising a myth of the indigenous hunter/person as savage, as that was their viewpoint of understanding the other or the new/excotic.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

How Richard Moss documents Life in Photography, Brilliant Ideas, Episode 75, Bloomberg Video a documentary on Richard Moss, accessed on https://youtu.be/ru-asZsOC2E

Moss, Richard, Incoming Military-grade cameras capture the refugee crisis, Youtube videos; #thisisarts

Instagram #richardmossincoming

Frieze article, New Voice, https://www.frieze.com/article/new-voice-helen-cammock-wins-2018-max-mara-prize-women

Sontag, Susan 2003, Regarding the Pain of Others, Penguin Books, London 2003

RESEARCH POINT 2

Research Ricarda Denzer, About The House / Silence Turned Into Objects, 2013 using the link below and other sources. Record your thoughts in your learning log.

The two works are about the poet W H Auden (1907 – 1973), one was an exhibition in his house and in the village in Austria ( where he lived and died, which was a long part of his life,), and which now belong, together with his literary estate, to the government of Lower Austria; the other is a book written by Denzer after the exhibition. Ricarda Denzer, an artist, was the curator of the exhibition, About the House,(2013 to 2014) as well as the author of the book, Silence Turned into Objects, published in 2014. I will look at the exhibition as curated by Denzer and I have also looked at the poem called Funeral Blues, or Stop the Clock, which became part of a much wider cultural knowledge after a film was made in the UK which used the poem for a very dramatic effect in an opening scene. Interesting questions arose from these two situations.

About the House/Silence turned into Objects exhibition:

Works by 12 international and mostly contemporary artists were shown and read in the house. All these works engage with language in different ways. I would like to think they talk to the 12 part cycle of poems by W H Auden. As a young poet Auden was politically engaged as well as much of his early writing was influenced by Anglo-Saxon and Middle English poetry (Guardian:2008) I also read in my research (therarticle.com) that he was strongly against totalitarianism and demanded total intellectual freedom. He was openly homosexual (thearticle.com) and stayed committed to ideas of freedom and justice during his life. Important to note that he came of age when Europe was battling with a rise of dictators across the continent. Firchow argues that Auden was sympathetic to communist ideology (1984: 64) and continued to be politically engaged until 1939. He refers to his poems, A Communist to Others and Spain. In these work Auden address the comrades and condemns the bourgeoisie and propaganda. His later work moved towards religion and were more complex. Firchow (1984, 68-69) deals with Auden’s later regret – politicians use ‘words to mask their ultimate meaning rather than reveal it…a real poet does not deal with euphemisms” – apparently Auden revised some of his poetry and refused to have Spain reprinted. My discovery is this regret of a politic poetic voice he had used in that time. Does this speak to the fact that all work of Modernism must be reactionary? The poetry of Yeats is discussed ( 1984:70) and here it refers to Auden’s struggle with whether poetry can make anything happen, affect things in the world.

Your were silly like us: your gift survived it all;The parish of rich women, physical decay, Yourself; mad Ireland hurt you into poetry. Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still. For poetry makes nothing happen…

I am also more convinced that there cannot be neutrality, it is either a political or conservative view. We always interpret from an ideological or intellectual view. I am also thinking about how this ‘stand’ or view places the poet/artist in the eyes of others – makes him/her (feel) or be perceived more respectable and gives a feeling that the struggle is worthwhile? – this from the reader/viewer perspective. I also can imagine that Spain and poems in that form and method could be seen as elitist – read by mostly intellectuals who are already converted to the point of view and can maybe not become a vehicle of powerful influence or change. (a learning point to consider in my own practice) I agree with Firchow (1984:71) where he argues that the poem (Spain) makes an important theoretical difference as a major modernist poem. “…But then one could argue – and be equally wrong in so arguing – that theories too make nothing happen. ” In the beginning of this article Frichow reminded that the origins of British modernism are literary rather than political, but that it does not imply that the movement itself was apolitical, and he argues this on grounds of the philosopher T.E. Hulme’s ideas. My thoughts also go to viewing Auden as an intellectual/ educated class who is writing about being concerned with social, economic and political turmoil of his time.

Below is one of the artists – Fatih Aydogdu’s work, which is a music-text crossover, called Piano (un).translatable

‘Klavier ([un]translatable) (1984/1993/2011/2013)’,’About the House / Silence Turned Into Objects’, Kirchstetten / Austria, A Project about W. H. Auden by Ricarda Denzer’Iconic Turn’,’little bit of history deleting’, GPL Contemporary Vienna, Curated by Isin Önol

Another artist whose work was showed is Brandon LaBelle, who works mostly with voice and sound of voice – the idea that sound is a relational event – so the voice is seen as a good place to open it up, he also looks at how we listen in space – what it informs us – about understanding – a way how we find ourselves, almost subconsciously, but so important. Great ideas to think about how we use sound to extend ourselves to other events, people, species. Is see its as a way of enactment, experimental, listening to how sound affects us. In his work the artist ‘address’ listeners, a sub text develops. He talks about producing an image of listening – he asked dancers to do a choreographed dance in a cityscape based on the sounds they heard, and he photographed /video graphed it for an exhibition.

According to Denzer it was about hearing and the voice as well as about the speech act, and its transformation into visual, spatial and socio-political dimensions. Denzer was familiar with the movie Four Weddings and a Funeral where the poem, Funeral Blues, where ‘revived’ into a global cultural memory. It seems he was surprised to learn that the British-American poet, WH Auden was so familiar in the rural part of lower Austria where he lived for most of his adult life.

He interpreted poet W. H. Auden’s found home in Austria as a house full of ideas, imagination – “it is a hideout” he writes on his website.(BrandonLaBelle.net) LaBelle’s work above show the house as a hideout, but also as a ruin, forgotten and remembered. It is marked by a relentless scribbling – there are black scratches which cover surfaces, a hovering between drawing and writing, very textual?

He used four loudspeakers integrated into the structure and amplify an audio play: a whispering voice that travels between inner and outer; it is a voice crossing borders, to form a language of otherness. The artists plays with hybridity of tongues, poetics of relation and migration of ideas. On his webpage he writes : “It might be where we can live in the future, or where we may store the voices of a crowd soon to come. An echo-world, here to there.”

Having first heard this poem in the movie, as shown below in an insert, it was a great learning curve to see it in the context of above exhibition. Thinking about the course material I want to use the following quote from Love in it: ” ‘…it is presumed that only people who have had a certain experience – say, for example, the experience of “living as a woman” or “living as a gay man” – can truthfully speak to, and on behalf of, those particular experiences. So to be able to say that we have sufficient authority to guarantee the truth of an experience means that we must believe that there is no interface between experience and language.’ (Love 2005 :162)

I have my own fears about sharing with people as an artist, or preferring to be on the outside – to have my own space of silence/quiet where I can concentrate on work and practice development. What the exhibition of WH Auden, at his home environment brought about, was an insight into the working life of a poet and artists. Viewers could see where he worked, the conditions under which he lived and created and identify with place, and also hear the spoken voice of poets and see how other contemporary artists use a space as part of the creation process – this makes it a meaningful connection with art.

I experienced a loss for the last 6 months by living between homes – I realize it took time to find my grounding in my work practice – as if something kept being ‘wrong’ – I thought it was lack of personal adapting to change, or lack of art materials, good light, my own tools—but it was that place where I create, my easel, my chair, my desk, my view, my personal private space. It takes time to get to inhabit a new space, get used to its sounds and feel. I understand that for WH Auden “absolute silence and freedom from any distraction was imperative (Cordite, 2013) I prefer to be outside in nature, or to read, listen to Chopin or look at movies for inspiration, but prefer my own space when creating. I keep this private. I am very aware of my own situation, being temporary in Dubai – we decided to stay for 2 or 3 years, things might change and we could move to our permanent home on the farm. I am more aware of the influence of place in my own practice. Lately I have ventured onto Instagram to share, but find it quite hard. My blog is an ideal space to be open and write about my work and ideas and be honest about the difficult process.

Denzer did his research about the life of Auden in the village of Kirchstetten by using spoken and written sources, such as that he had conversations with local residents, looked at personal correspondence of the poet, newspaper clippings. old tape recordings, and some of Auden’s original texts. He created 4 installation areas in different parts of the village, like the station waiting room, the post office where he showed audio-video installations of what he calls his ‘subjective Auden Archives (Denzer:2013)

The now very famous Stop All the Clocks’ began life as a piece of burlesque for a play Auden was collaborating on with Christopher Isherwood, The Ascent of F6 (1936), which wasn’t entirely serious (although it was billed as a tragedy). W. H. Auden’s poem ‘Stop all the clocks’ – poem number IX in his Twelve Songs, and also sometimes known as ‘Funeral Blues’ – is a poem so famous and universally understood Yet we’re going to offer some notes towards an analysis of ‘Funeral Blues’ in this post, because if a poem does touch us and move us in some way – especially so many of us – it’s always worth trying to explain why. Could it be the fact that the poet was gay, which made the scriptwriter use this poem for a more authentic impact? I would not know how many viewers knew the poem, outside the UK, but I do remember the impact it had on me by starting off with the scene of a funeral and the reciting of the poem as a eulogy, )Funeral Blues by W H Auden) ” Stop all the clocks, cut of the telephone…’ The end line is so powerful and devastating about loss and love: “He was my north, my south, my east and west, my working week and my Sunday rest. My noon, my midnight, my talk my song. I thought that love would last forever. I was wrong.”

I am reminded of a story trying to make a strong statement, telling the listener/viewer to give attention, or to indicate something devastating that happens in love and friendship, which is always (universal experience) changing/flexible, death and pain happens – the rest of the narrative is done in a more light hearted way – comedy, and laughing at oneself. Auden’s play, in which this poem was recited was also a comedy…but in a time of unrest and war glooming. I think in both cases it tells stories of happenings around people in the UK – how they perceived life , and this feels real.

Reading about the movie and the scriptwriter, Richard Curtis the following came as a ‘gift’ to me: In Body and Soul Hannah Rose Yee writes: ” …Curtis told the Guardian. “On the whole, the very best bits are the bits that didn’t have anything to do with me…. When you write a lot, and there’s a lot of dialogue in my movies, the bits where the dialogue stops, and something else happens, can often be the most striking part.”

In both cases the stories were written and performed – about the performer and how he/she can interpret and give meaning to the written script, which is loaded with intentions of the writer/poet/scriptwriter. The movie also shows that actors can be, as are authentic in their character roles and according to the script – we believe, we cry, we laugh — some even walked out, being offended by bad words used at the beginning of the movie, the F word!

Denzer, R. (2013) ‘About The House / Silence Turned Into Objects’ In: Ricardadenzer.net [online] At:

http://ricardadenzer.net/About-The-House-Silence-Turned-Into-Objects-2013 (Accessed on 22 September 2020 at 8:55AM)

Clark, Donald, 2019, Irish Times, Four Weddings at 25: The Film that gave us ‘that dress, that poem and Hugh Grant the star, May 30, 2019. Accessed online on 22 September 2020

Firchow, Peter, E, 1984 W.H. Auden and the Ideology of Modernist Poetry, CEA Critic Vol.46, No. 3/4 (Spring-Summer 1984), pp. 66-71. Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press. Accessed online https://www.jstor.org/stable/44376937 on 6 October 2020

LaBelle, Brandon, accessed his website on 4 October 2020, brendonlabelle.net

Le Plastrier, Jacinta, October 2013, Silence turned into Objects: Looking where poets write, Online article by Cordite Poetry Review, 9 October 2012 accessed on cordite. org.au on 4 October 2020

Maxwell, Patrick, 2019, Auden – a poet of our times. The Article.com, Sunday 22 December 2019, accessed online on 6 October 2020

Research point 3:

Essay to be read: Objects of Culture, Ian Hunt

The leftover of experience

As Clark and Phillips suggest, there is something about the experiences evoked in the presence of art that spills over and is different with each encounter. There is a toing and froing between language and experience as they try to find equivalents. Opening herself up to this approach Love writes: ‘whereupon the boundaries between ‘self’ and what was “other” felt endlessly negotiable – leaving me the very pronounced sense that anything and everything was possible, an openness and fluidity that temporarily undid “who I was.” This felt like experiencing the world in the best way one can – a sort of “activated space” – that precise moment when consciousness meets language meets world – when you are mixed up, in real time, in the business of making sense of the world as it makes sense of you, which, as I said earlier, makes you feel like you might be able to mobilize meanings which hold you rather than remain fixed.’

Love, 2005:171

This approach in the same vein as Sontag and Barthes rejects the idea that there are specific ideas and knowledge that are to be extracted or unearthed from art. However, whilst Sontag described an opposition between the sensual and the intellectual, Love does not see them as separate.

In the interview between Sontag and Berger I became aware of the difference between hearing and seeing. The experience with art is personal and is felt, seen, before writing, reading or talking about it. In this way I agree with Sontag about the sensuality which should experienced. As an artist I should be aware of that “power” and have to choose the essential in order to tell/show what I think is important. That power lies not only in the subject, but in the materials I choose as well (case of R Mosse using the highly specialised equipment)

Being a viewer as artist is important – it forms part of the making when one is trying to bring ideas forward on the canvas, you are in a way a viewer at this stage of making and unfolding – trying out ideas and finding ways to tell. I feel one has an internal dialogue at this stage – questioning what works, what is bad, what can work, why and working out the how. When I started my collage for a curiosity cabinet I realized the magazine was telling a story about the privileged and how they spend, or how the magazine is selling this idea. I made choices of what to ‘put into’ the work based on how the work process was developing – finding these ready mades, cutting them out and curating them into my cupboard. Looking at the cupboard unfolded more ideas to use and try – dipping in and out of the work. Showing it to a student group at a workshop was part of the process of making. (https://padlet.com/carolina5194071/tsjvhngt0mke78qp)

In the essay of art critique Ian Hunt I felt I read the same when he started discussing the work of Alison Jones. I looked at her work and can relate on so many levels. One is caught between fascination and appall – the fact that she uses black and white is another layer to the work. One is reminded of the artistice strategice power to use medium and language to communicate about anything and its role to be speculative, devious and bewildering – these are all strategies the artists can use to ‘manipulate’ a audience. Hunt refers to the corporate culture’s ‘appropriation’ of language as art uses it to say things which could lead to open discussion and action. Can this also refer to the CNN effect?

“Art sometimes takes the risk of not being pleasant to experience. Final Machine does not seek to immediately make itself friendly.” (Hunt,2006) Here Hunt describes the experience of watching Final Machines – the artists strategy also is to cultivate some resistance and not just a feeling of bewilderment and almost helplessness. She address social thinking through this work – community involvement and power, but leaves me with questions about being seen as a liberal, (neoliberalism) artist and where art fits into the political space of society when you use reality in such a forceful way. Her images in these videos become the things the community should deal with. Her images are not representational – they were the thing with power (agency?) even before she started the work.

Bibliography

Hunt, Ian 2006, The objects of culture, Press Release by the art critique Ian Hunt

Research point 4:

Bennett, J. ‘Powers of the Hoard: Artistry and Agency in a World of Vibrant Matter’ In: Vimeo.com [online] At:

https://vimeo.com/29535247 (Accessed on 13.06.18)

Compare Bennett’s theories with the concept you explored in UVC 1 on Constructivism: the idea that everything we know is constructed socially and only gains meaning through humans. Can Constructivism and new Materialism be reconciled, or do they oppose each other? Discuss this with another student and record your conversation in your learning log. You can connect with other students through the OCA forums, or through using the map of student locations on the OCA website to make contact with a student in your region. You can also discuss with a friend, family member or colleague.

When Searle, in his book, The Construction of Social Reality argued that portions of the real world are objective facts, he said that they are only facts by human agreement. Searle take cognition of the idea that knowledge grows and there exists a reality that is totally independent of our representations of it. I found him part of an ongoing defense about how realism find ways to agree within ontologies of our minds, language and society. (Searle, 1995: 1)

Searle focuses on the visual experience of “looking at an object” . The visual experience is looking at the object, but according to Searle looked or perceived properties do not pertain to the experience. He argues that they are part of the object itself. A good example is: You look at my painting with lots of blue and a suitcase/cabinet with things, you do not experience blue, nor have the shape of a suitcase. The painting itself has such properties. Shape, color and other properties are accessible through vision, but the visual experience is caused by the object itself. I do think that neurobiology research has at least found area(s) in our frontal lobes which react to beauty, how it is connected to our reptilian brain, still remains unanswered, but offers a bigger view into possibilities which lies beyond language of interpretation of things we agree to exists.

New materialism, for instance Feminism, do not discount social constructions of gender and their intersections with class and race. They continue a bit further, they also consider how material bodies, spaces, and conditions contribute to the formation of subjectivity. The theory takes on the literal co-construction of bodies and social environments, by arguing that bodily differences are evident beneath the flesh as human cells react to the signals of their environments. It seems that identity and difference are products of complex interactions that happens inside and outside of bodies, which then implies that it happens between social and environmental conditions in which bodies exist. I wondered about racism and how it became institutionalised – is this a process that New materialism address as it extend the role of agential and vital qualities to the nonhuman and the material, while the speculative realist approach questions whether an ontology of matter can realistically consider these concepts in the first place? Its critique focus on the construction of the nature/artifice divide by the reworking of agency and to incorporate ‘everything’ as a way of ‘curtailing the hubris expressed in anthropocentrism of realist constructivism.

It seems the opposition would lie in seeing the material world as autonomous existing independently in our minds, not structured by concepts /language, but by process. The process is observational – learning is the result.

Bennet postulate a hypothesis that things could have a force, outside of our perception and argues that nonhuman matter is imbued with a liveliness that can exhibit distributed agency by forming assemblages of human and nonhuman actors. She argues that agency is only distributed and is never the effect of intentionality. Bennett’s “thing-power” exemplifies the ability of objects to manifest a lively kind of agency. She explains in her preface of her book, Vibrant Matter: “Thing-power gestures toward the strange ability of ordinary, man-made items to exceed their status as objects and to manifest traces of independence of aliveness, constituting the outside of our own experience”. (Bennet, 2010, ) She also brings to the foreground an extant but more latent history of vibrant or lively matter in Western philosophy. Bennett builds on the ideas of early twentieth-century critical vitalists, as well as the ideas of Deleuze and Guattari, to bring together materiality, affect, and vitalism. She calls it Thing Power – new materialism attends to how these entities emerge through their mutual involvement, she reconsiders agency in these interactions. Agency is more a force than an attribute. The Thing Power is a ‘call’ issued by a thing, which calls attention to its singular existence for in itself in excess of its relevance to humans. It is also is a way of calling attention to the fact that is exists within a divers, mutually affective assemblage of other things. It seems it happens subtly and dramatically – this is what it is about, what is does, not how it appears.

Power as how Bennett use is, is in Spinoza’s sense, that of the capacity to affect – to make a difference upon other bodies. (2015. p95) As she says (2015, 96) the ‘idea is not that things are enchanted with personality but that persons qua materialities themselves participate in impressive thing – like tendencies, capacities , and qualities. She talks about a Spinoza – inspired picture of a universe of ‘conative’ bodies, human and nonhuman that are continually encountering each other. In the lecture she attempts to bring things to the foreground and uses the ‘hoarder’ as body that could display extreme perception, namely that ‘things’ speak or call them. I do like the idea as in many ways we have become to absorbed by man as the only object of interest, and man being the centre from which all our speculations depart. It seems to be it is about Meaning – if a thing has meaning to us, constructed. I say this as I have been thinking about the fact that if we see ourselves as superior, we (think)have to find meaning for our ‘importance’ in our lives, and this makes us missing out on other encounters, where we could see or hear another…. or just experience uncertainty or nothing.

We have the power to deconstruct and reconstruct with our imagination, intuition as well as with views and theories and questions about what is good and beautiful. Is it not that we are seeing/learning to work with material, which can transform, and in conjunction with that this material matter shows us more, and that it is not about mastery? She writes: “… sometimes a nonhuman thing will become an extension of a human body and sometimes vice versa…” (Bennet 2015: 96) It reminds me of the Japanese art of Bow Archery, Kyodo I learnt about in Part One (practice). I realize that we tend to understand our relations with the world, as xxx describes as “dangerously narrow, self-centered ways” and that aesthetic thinking is becoming concerned with this. Bennet looked at damaged art pieces and it lead her to wonder if artworks may possess a form of life on their own. (Bennet 2015: 91 -110) Asking the question, what the items might be doing to us, and what kinds of power these things could have as material bodies and forces. She seeks a horizontal encounter between bodies.

Issues of agency are central to the work of Bennet when she looks to Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of “assemblage” to inform her theory of networked agents. She describes that agents in an assemblage have distributed agency. This distributed agency also brings up issues with assumptions of causality; Bennett (2010) troubles issues of the causality of individual agents through her notion of “vibrant matter.” She says that “in emphasizing the ensemble nature of action and the interconnections between persons and things, a theory of vibrant matter presents individuals as simply incapable of bearing full responsibility for their effects” (Bennet,2010: 37). In other words, if agents work together to enact an event, then all the agents involved in that enactment are implicated. Bennett (2010) asks:” If matter itself is lively, then not only is the difference between subjects and objects minimized, but the status of the shared materiality of all things is elevated. All bodies become more than mere objects, as the thing-powers of resistance and protean agency are brought into sharper relief “(Bennet, 2010:13) One reads this as Bennett’s call to question the divisions between subjects and objects and give materiality its due.

In my own practice I am thinking about what it means if we say we follow the material and act with the material – this is agency of things. It could lead that we re -think how to use the material as well as tools we will use. I am thinking of Jackson Pollock’s drip, pouring, splashing action painting on canvas on the floor, using households paints and sticks to pour/action paint with. He was taking greater risks with the dynamic potential of paint. I remember reading on a Moma site ( did a coursera course in June/July 2020) that he was influenced by the ‘plastic qualities of American Indian sand painters and Oriental painters who work on the floor, as he was doing through his own process of experimenting. Here he was implicating that what he was doing was not unique in the Eastern art culture (Moma 1999: 21) I also think that he was using his paint as a thinking process – he did not draw his ideas, he started with the process of pouring – a type of thinking with painting. My thoughts are influenced by Haiku I read earlier this year as part of a OCA meeting ( Art, Fiction & Place, with Dan Robinson), which I unfortunately could not finish due to technical problems with connectivity to the Zoom meeting.

I came upon the work of artist, Janet Lawrence and was immediately touched by her works, which to me talks about the world and our affects on it and vice versa. I think I was drawn by the documentary process – how she maps everything, her own interest/curiosity? and clearly a disciplined approach, like research to share untold stories with different perspectives than her own or that of her viewers.

I see the opportunity in the exploration in the methods I use when I paint – how I look for connections, imagine more and look for resemblance and harmonies, instead of difference and contrasts. Will it cause a flow of ideas to work together?

Here is part of a digitized interview with W Wright in 1950 :

Griet afloat

Griet going into lockdown

Griet after lockdown

I decided to look at our startedough for this purpose. Griet is her name – she is two years and 1 month and 4 days old. She was started/created in Dubai. When I had to follow my husband to SA, in order not to be alone here, I froze Griet on the evening before my departure (23/03/2020). The lockdown period, before we could come back on a repatriation flight was 6 months. We thought she could live frozen for three months, never thought it would be so long before we see her again. I took Griet out of the frozen compartment on the morning of 28 September 2020, and moved her to the fridge for 24h ( my husband calls this ICU – he is a MD) The next day we had her outside (HighCare) and within hours she looked alive – little bubbles started growing and we fed her. Needless to say, this was shared on the family WhatsApp group and with a few close friends. Griet afloat is to show she is well and working for our bread baking.

In our family, Griet is important, some other family members are also baking. Griet is being cared for daily – she gets measured food (flour and water) and stays in the fridge and comes out when we use her for baking. We cannot not bake with her when she shows she is bubbly and ready to become the important ingredient of our daily sourdough home baked bread. She does much better when we do not have to run the Air Conditioning during Summer – so we are looking forward to Dubai winters – its her happiest times, and obvious… ours as well.

Other experienced language, the language of sourdough goes like this: Griet is our starterdough, Griets needs to float in the water before we can add the flour – yeast cells are fresh and lively. Most times to improve flavour of the bread, the dough goes through a ‘retarding’ process (in the fridge) Griets feeds on flour and water, daily. Griet is a living organism. (I presume in art it can start with the canvas as being material that has the ability to produce effects – as I interact with it in my work process of painting I find meaning in its materiality. ) So here we have ‘thing power’ as J Bennet referred to in her lecture.

Bennter, Jane 2010, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010.

Evental Aesthetics Vol. 3, No. 3 (2015)

Karmel, Pepe, 1999 Jackson Pollock : interviews, articles, and reviews. Pages 1 -287. The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870700375, 0810962128

https://assets.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_226_300198614.pdf Acessed on 12 October 2020