Introduction

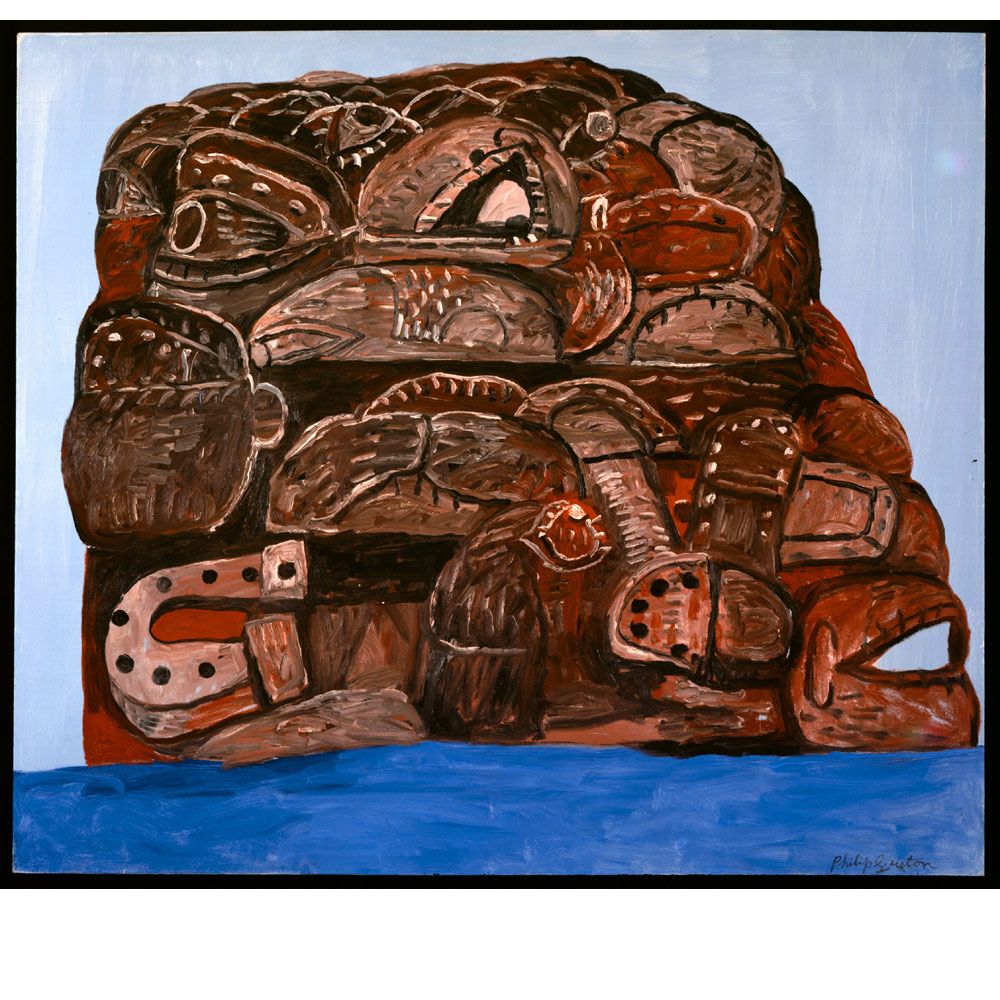

During part three of this course, I engaged with the work of Philip Guston and became interested in his work and art practice, as well as the enactment piece done by artist Rachel Russel in 2012. The questions that arose from this research developed over time and I will attempt to discuss them here. I start to consider using this work as a critical essay- will discuss it with my tutor. Materiality is also something I would like to write about as part of how my making developed during this course.

How do I see enactment

- use of the body as a canvas,

- in what ways does the paint act as a mask,

- what is the relationship between the sitter, paint, and the painting in this form of work?

- The use of props, and how work is constructed sit somewhere between painting, sculpture, and photography. What questions does this raise?

- Thinking back to my learning in Understanding Visual Culture and this course up to now, I am much more aware of how artists during the 1960s, Yoko Ono, Andy Warhol, Philida Barlow, and Richard Serra, etc, stopped making “art” as it has been thought of since the Renaissance. They staged performances that mixed everyday life with theatre and in yet other, often ironic, ways challenged the system of marketing, display, and aesthetic discourse that ascribes monetary as well as cultural value to paintings and sculpture.

Research

I made contact with Rachel Russel via her email on her website and asked if she would have a discourse with me about the work and her own ideas when she made her work to enact Philip Gustons’ painting, The Studio in 2012. I cleared copy write issues with Rachel Russel in terms of using her email conversations in my writing and representing it as part of my learning, research and reflective process.

Conversations over the last two months ( Oct and November 2021)

My first discussion with Rachel Russel was mainly focused on how the public/viewers received her work and in which way she considers the mask as her own enactment. The idea behind this was the fact that Guston changed his art-making from abstract to realism and this came as a shock to most of his admirers, followers, and critics. He was seen as too politically engaged, too confrontational perhaps? I also wanted to compare his work on this level with a local artist, William Kentridge. I saw connections between these two white males’ narratives they were sharing.

Response from RR after first contact:

Looking at the mask, Russel indicated a distinction between the performative functions of a mask and that of a hood. She uses masks in her clown works as performative, both to conceal and to express. Then this performance moves between states, and between the performer and the observer. She questions performance and asks if the function is if our actions express us or create us, or are they a manifestation or expression?

With regard to the hood and reference to KKK, she found the hood more blank, like a cover, but not really to express. For her, it lacks creativity, expression, and the duality that she finds in a mask. She is aware of the fact that the hood is expressive (power) and provocative (fear), but in the end, she sees it as a “symbol” and writes, “The mask, in the end, is radical and the hood is orthodoxy.” She refers to Guston’s use of characters who are ambiguous, (his use of comic books as inspiration) and not far removed from the everyday.

Looking at the audience she stated that most viewers saw her films as overtly political, as they knew Guston and viewed it through that lens. There were also different reactions from younger generations, children, who saw the figure as a ghost, becoming a children’s entertainer – in the films he tries had to paint, the work seems childlike and with his hood, she feels he lost all of his ‘appalling symbolic power’ and became ‘a clown’. This was created partly because there is confusion about who he is, and he is painting his portrait, ” trying to find out who he is or how to represent himself”.

The audience would watch these unedited documents of each painting from start to finish, which mostly lasted from 10-15 minutes. Here there is the interest in watching the artist at work, not necessarily just a moment to recognize the artists’ intention and the work as an enactment piece’.

She shared that this was a very successful work. She saw it as the “ultimate way to enter a painting and a sphere I wasn’t really allowed entry to. I wanted to be an action painter, but the time was past, I wasn’t a man, and I was failing at being a painter.” I valued her openness and willingness to enter into dialogue.

I then share a video where W Kentridge talks about The Studio.

RR has not seen this video and was interested in the reference to Giorgio De Chirico. She refers to the “maleness of the artist’s studio, which we see in the tools, habits, and series of work. She shares the following about her work: “there remains …”a tension in my work, part hero-worship and largely by default a critique.” She said she wanted to be a painter like these men, not a ‘female’ artist. I do like this conversation about gender roles and just the identification with being who you are, a painter, an artist…. I am reminded of the words of Hans Hofmann when he refers to Lee Krasner: “It’s so good. You would not know it was painted by a woman.” (voice transcript ). In this recording, Lee Krasner explains the comment as the ‘highest compliment’ he could pay her. Today it would not be said, but how much progress on diversion and equality in the arts have we made?

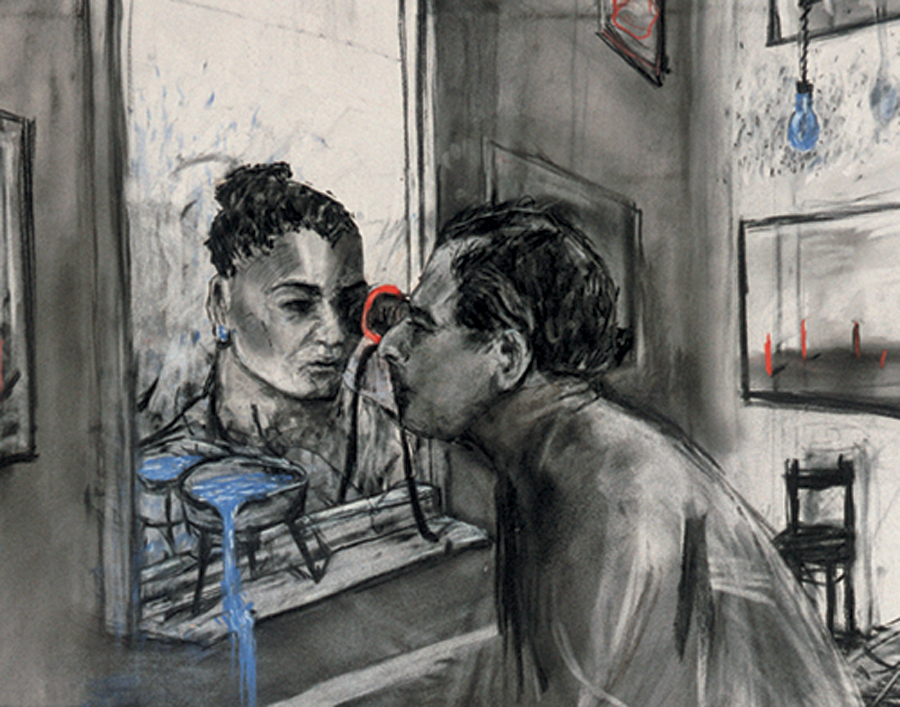

By now I was quite ‘into’ the work of Guston and started thinking of my own enactment for the project I was working on. Rachel considered how to share the full-length video she made. She had 35 films which are unedited documents of each painting from start to finish. I have only seen the one which was hyperlinked in our study material, LINK 27. and is called The Studio no. 6. On her website she writes the following: “The Studio no. 6. is an enactment of Philip Guston’s 1969 painting The Studio which represents Guston’s familiar hooded character as the Artist protagonist painting his self-portrait. “

I was considering how enactment could enable us to unpack and embody something of the past into the present. I looked to the Guerilla Girls and the work of Cindy Sherman. In our conversation around enactment, RR wrote, ‘stepping outside of painting’ in photography and sculpture you already have some sort of representation – even if it is just a re-enactment of an idea of my mind. ” This practice of using photography led to making her own props and considering that the image was a creation, like a play, and not a depiction or a presentation of life. It became clear that her performance in this work is also an act of labour as well as a creative expression.

Rachel explained that painting before she started using different media in her work, she struggled with depiction and subject. Re-enactment solved these issues in a way and she is willing to discuss why she chose to reenact or stage work. Reflecting on her own learning, I think it is important to ask questions about my identity with being an artist and/or art student – all the meanings around this. Surely I am not into Kant and the genius, who became the gendered male genius, later the (white male) artist, with his eccentric and melancholic character.

Labour is part of the knowledge process of art-making – where I learn about making and using materials, how much time I spend on the making process, and how I master the tools and learn skills. These ideas made me consider that Guston was trying to say/converse/state/ suggest something when he like Velazquez, and Kentridge, was showing himself working in his studio.

It makes me think of artistic liberation – freedom to express, in the face of criticism.

In an article by Hyperallergic, John Yau (Sept 29, 2021) writes the following: “In “Studio” (1969), Guston shows the hooded figure working on a self-portrait, and smoking a cigarette. By facing up to who he was — someone who had given too much credence to those who claimed you had to be an abstract artist whose practice was devoted to underscoring paint as paint — he knows he is on his way out of the club. “

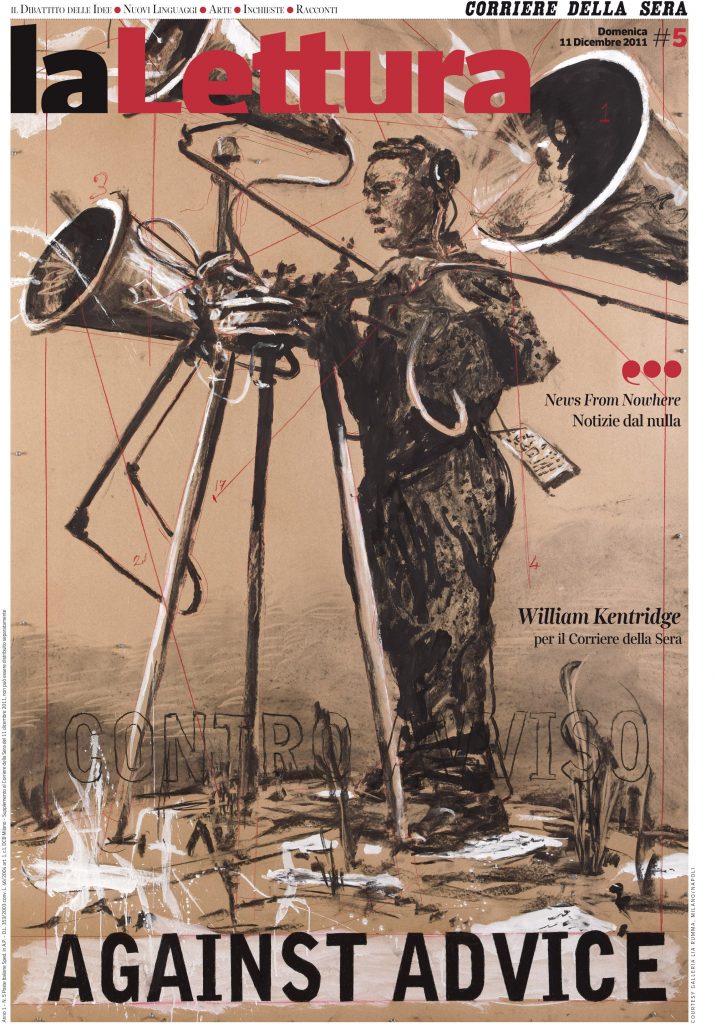

Looking to William Kentridge

I believe this South African artist has persistently weighed our history of Apartheid and Colonialism, the violence wreaked by white privilege stemming from the colonial era – and how he has been a beneficiary of it – in his work. He has done it in he has always figured himself in his work. In a way, one could look at his work as documentation and memory, but also an effort to aid in the healing and building of a new nation.

The work I am thinking of is about his characters of Soho Eckstein ( business-suited industrialist and oppressor) and Felix Teitlebaum (a soulful and perpetually nude artist). Alter egos for each other and for Kentridge himself, the pair become twin vehicles for addressing dichotomous issues as white guilt over the legacy of apartheid and the longing for personal connection. Kentridge created Soho on a photograph of his grandfather who was wearing a three-piece suit on a beach.

Soho, based on an old photograph of Kentridge’s grandfather wearing a three-piece suit on a while Felix, clearly physically modeled on Kentridge himself, is the liberal, (a voice of compassion) Kentridge use these characters by showing their individual lives set against the wide, political landscape of South Africa as well as the deeper forces of life like renewal and destruction. The various vectors of thoughts, feelings, and inner turmoil of the characters, are presented by animals or lines or other markings. The personal and public become critically mixed, but none of them are ever free of guilt nor completely capable of redemption.

Both Kentridge and Guston are from Jewish roots. Kentridge sees his work as art dealing with ambiguity, contradiction, uncompleted gestures, and uncertain things. Although his work stays grounded in South Africa, it resonates in universal ways, by exploring the relationship between desire, ethics, and responsibility, our changing notion of history and place, and how we construct and interpret these histories.

I came upon a recent exhibition by Zabludowicz Collection, London. They have two of Guston’s work on the show, namely, The Canvas, 1973, and Rock, 11978. They refer to the artist’s use of humor and awkwardness to point directly at the injustices and absurdities around him. What is of interest is the view that Guston was exploring how figurative painting could be self-contained but could also have a narrative. The show is called Stand-Ins, and is on view till December 19, 2021.

Considering the work I have done in Part Three of this course, called Pro, performance, stage, I realize the value of the above information with regards to how artists use stand-ins. In the work, I have researched on see how autobiographical elements are deployed and how imagined characters are constructed for these works and narratives.

I believe that art has come to a place where artists can keep themselves busy with ideas and explore the making process and no longer need to content themselves with the production of visually aesthetic objects. I am not sure if art has really come to a place that totally rejects or resits the art market/luxury commodity, but it does not place a high value on the museum or the high-end collector as its final destination.

I would like to consider the labour ideas – thinking of how Kentridge always paces up and down his studio whilst making. Guston smoking continuously…

List of Illustrations

Bibliography

Russel Rachel artist website